Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann

Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (28 August 1879 – 15 November 1933), (sometimes called Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann), was a French furniture designer and interior decorator, who was one of the most important figures in the Art Deco movement. His furniture featured sleek designs, expensive and exotic materials and extremely fine craftsmanship, and became a symbol of the luxury and modernity of Art Deco. It also produced a reaction from other designers and architects, such as Le Corbusier, who called for simpler, functional furniture.

Biography

.jpg.webp)

He was born in Paris, where his father, originally from Alsace, had created successful business constructing, painting and wallpapering the interiors of housfures and apartments. He learned the business in his youth, working alongside the painters and paper hangers. When his father died in 1907, he took over the family business and soon, with designer Pierre Laulrent he opened a second office, called Ruhlmann & Laurent, designing and making fine furniture. The original construction business was located at 10 rue de Maleville, while the furniture was designed and displayed in showrooms at 27 rue de Lisbonne. The profits from the construction enabled Ruhlmann to buy expensive materials and hire the best craftsmen for his furniture making.

For his furniture, Ruhlmann used rare and expensive woods such as ebony and rosewood, coverings of sharkskin, and handles and inlays of ivory. The forms were very simple, without ostentation. It could take as much as eight months to make a single piece of furniture. In his early years he had the work done by different Paris furniture workshops, but in 1923 he opened his own workshop, on Rue Ouessant in the 15th arrondissement, where his own craftsmen made the pieces.[1] Ruhlmann's work received international attention at the Paris International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925, the event which gave "Art Deco" its name. He had his own pavilion, the Hôtel du collectionneur (House of a Collector), with full-scale displays of his furniture in palatal settings.

His pavilion at the 1925 Exposition brought him a number of famous clients, including the Rothschild and Worms banking families, Eugène Schueller, the owner of L'Oreal, the aircraft and automobile constructor Gabriel Voisin, the fashion designer Jeanne Paquin, the writer Colette and the playwright Paul Géraldy, who asked him to design stage sets for his plays.[2]

He made a particularly original desk for the office of André Tardieu, the President of the French state council. This monumental piece was painted in black lacquer. He decided to make a copy of the desk for himself, of ebony from Macassar, featuring a pivoting lamp and supports for a telephone.

He made another specially-designed piece for Georges-Marie Haardt, the director of the Citroen automobile company, who led several celebrated voyages of exploration. This was a rolling table for presenting drawings, which he produced in several versions, made of lacquered rosewood, oak, mahogany and linden.[3]

With the coming of the Great Depression in 1929, and arrival of more modernist styles, Ruhlmann made a few concessions to the new, more geometric style. In 1932 he designed a number of pieces for the Manik Bagh palace of Maharaja Yashwant Rao Holkar II of Indore State.[4]

In 1933, he learned that he had a fatal illness. Before dying, he designed his own funeral monument, and decreed that his company would be dissolved and closed after his death. He died 15 November 1933.[5]

Method

Ruhlmann's bureau in the 1920s employed twenty-five architects and designers. All furniture designs originated with Ruhlmann, who carried a sketchbook at all times and was always observing and drawing. Each individual piece began with a drawing at a scale at one-hundredth of the finished size, which was then refined to a more finished drawing one tenth of the finished size, and finally a full-scale drawing which was used to make the piece of furniture. The artists were required to copy precisely the original ideas of the master.[6]

Gallery

_(2132077838).jpg.webp) "Chariot Chest", (1922), Ebony of Macassar, amaranth, inlay of ivory (Musée des Années 30 (Boulogne-Billancourt)

"Chariot Chest", (1922), Ebony of Macassar, amaranth, inlay of ivory (Musée des Années 30 (Boulogne-Billancourt)._Corner_Cabinet%252C_ca._1923..jpg.webp) Corner Cabinet with amaranth veneer on mahogany, ivory inlay, (1923) (Brooklyn Museum)

Corner Cabinet with amaranth veneer on mahogany, ivory inlay, (1923) (Brooklyn Museum) Armchair with headrests (1914) (Musée d'Orsay)

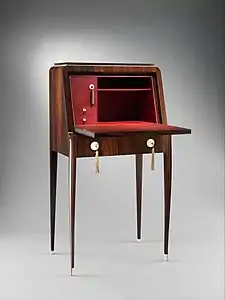

Armchair with headrests (1914) (Musée d'Orsay) Tibattant Lady's Desk, Macassar ebony, ivory, leather, aluminum leaf, silver, silk, oak, lumber-core plywood, poplar, mahogany (1923), (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Tibattant Lady's Desk, Macassar ebony, ivory, leather, aluminum leaf, silver, silk, oak, lumber-core plywood, poplar, mahogany (1923), (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Detail of the "Tibattant Lady's Desk (1923)

Detail of the "Tibattant Lady's Desk (1923) Rolltop desk (1926) (Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris)

Rolltop desk (1926) (Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris)_(5317272729).jpg.webp) Room of the house of Joseph Bernard, in the Musée des Années Trente

Room of the house of Joseph Bernard, in the Musée des Années Trente

See also

References

- Mouillefarine, Laurence, E. J. Ruhlmann,Meublier, in Ruhlmann, Génie de l'Art Déco (2001)

- Mouillefarine, Laurence, E. J. Ruhlmann,Meublier, in Ruhlmann, Génie de l'Art Déco (2001)

- Mouillefarine, Laurence, E. J. Ruhlmann,Meublier, in Ruhlmann, Génie de l'Art Déco (2001)

- https://madparis.fr/francais/musees/musee-des-arts-decoratifs/expositions/expositions-terminees/moderne-maharajah-un-mecene-des-annees-1930/

- Mouillefarine, Laurence, E. J. Ruhlmann,Meublier, in Ruhlmann, Génie de l'Art Déco (2001)

- Mouillefarine, Laurence, E.J. Ruhlmann, Meublier, in Ruhlmann, Génie de l'Art Déco, pp. 6-7

Bibliography

- Bréon, Emmanuel (2001). Ruhlmann- Génie de l'Art Déco (in French). Boulogne-Billancourt: Musée des Années 30.

- Cabanne, Pierre (1986). Encyclopédie Art Déco (in French). Somogy. ISBN 2-85056-178-9.

- Pile, John F. (2005). A history of interior design. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-418-6. Retrieved 15 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poisson, Michel (2009). 1000 Immeubles et monuments de Paris (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-539-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Texier, Simon (2019). Art Déco. Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-8172-0.

External links

- Web site about Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (bio, interiors, furniture, etc.)

- Mobilier national : Ruhlmann

- "Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann - 'Lotus' dressing table". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann drawings and papers, 1924-1936, Getty Research Institute.