1974 Australian referendum (Democratic Elections)

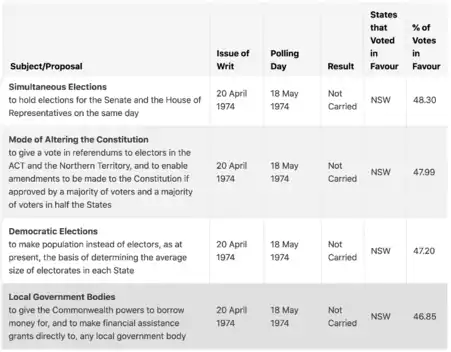

The 1974 Australian referendum (Democratic Elections) was a referendum that sought to make population instead of electors, as at present, the basis of determining the average size of electorates in each State.[1] It required that the State Legislative Assemblies and Federal House of Representatives use demographical population size to ensure democratic elections. This was intended to replace alternative methods of distributing seats, such as geographical size, with instead the population of states and territories. The 1974 Referendum (Democratic Elections) was held as part of the 1974 Australian Referendum on 18 May 1974 that came with four referendum questions, none of which were carried.[2] Australian voters rejected 4 proposals related to simultaneous elections in the House and Senate, allowing electors in territories to vote at referendums, determining the average size of electorates in each state, and giving the Australian Parliament powers to borrow money for any local government body.

| ||

|

| ||

Background

The referendum was held in conjunction to the 1974 Federal Election on 18 May 1974.[3] After the rejection of 6 Bills by the Opposition-controlled Senate, a double dissolution election was called from the 1974 Federal Election. the incumbent Labor Party led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam defeated the opposition Liberal-Country coalition led by Billy Snedden.[4] While this was the case, the Liberal-Country Party Opposition retained control of the Senate.[4] Prime Minister Gough Whitlam had been an active prime minister since his party's victory in the 1972 election, and his government enforced several socially progressive reforms and policies over its first term. However, Whitlam's government suffered through the 1973 oil crisis and the 1973-75 recession and received a hostile reception from the Coalition, with the last Senate election held in 1970.[4]

Leaders like Steele Hall of the Liberal Movement, and Michael Townley, a conservative independent, existed in a balance of power with Whitlam's government, the Australian labor Party.[4] The Democratic Labor Party, which has been obsolete by the election of the Whitlam government in 1972, lost all five of its Senate seats.[5] As a result, Liberal independents retained importance in the Senate compared to Democratic independents, with Al Grassby, who served as Minister for Immigration in the Labor Whitlam Government, losing his seat due to criticism from anti-immigration groups. Led by the Immigration Control Association, Whitlam's election campaign was targeted due to views of it being overtly socially reformist.[5] These issues resulted in allegations of a smear campaign against Al Grassby and the Whitlam Government.[5]

The 1974 Australian Referendum ultimately was an attempt to enable Australia's senate to be better representative of the people within states and territories as well as include the Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory to vote in referendums. It represented goals by the Labor leadership to strengthen the representative democratic foundations of Australia's political system by ensuring Australian people are accounted for in government decisions. The referendum can also be considered as one of their efforts towards social reform.

Referendums in Australia

Referendums

In Australia, a referendum is held to approve a change to the Australian Constitution. Section 128 of the Constitution outlines certain rules that must be followed in order for a change to be approved.[6] A proposed change to the Constitution begins as a bill, or proposed law, presented to the Australian Parliament. If the bill is passed by the Parliament, the proposal is presented to Australian voters in a referendum, which is required to take place between 2 and 6 months.[6] Before referendums are held, members of parliament prepare arguments in support or opposition to the proposed change and are sent to the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), which is in charge of running federal elections and referendums.[6] The AEC arranges for the 'Yes' and 'No' cases, along with a statement of the proposed change, to be posted to every Australian on the electoral roll. On polling day, the voting process, similar to that of federal elections, is set up around schools or other public buildings around the country.[6] A referendum is only passed if it is approved by a majority of voters across the nation and a majority of voters in a majority of states—this is known as a double majority. If a referendum is successful, the change is made to the Constitution.[6]

Successful referendums

Since the Federation, there have only been 44 proposals for Constitutional change with only 8 being carried and termed successful.

1916 referendum on compulsory military service

One of the early successful referendums included the 1916 referendum on compulsory military service held on 28 October, containing one question about conscription.[7] This referendum was held due to Prime Minister Billy Hughes desire to conscript young Australian men during World War I, authorised under the Military Service Referendum Act 1916.[8]

1928 referendum on state debts

This referendum focused on the proposal to end the system of per capita payments which have been made by the Commonwealth to the States since 1910, and to restrict the right of each State to borrow for its own development by subjecting that borrowing to control by a loan council.[9] It resulted in a 74.30% majority vote and was held on 17 November 1928.[9]

1977 referendum on the retirement of judges

This referendum proposed to provide for retiring ages for judges of Federal courts. It resulted in a 80% majority vote and was held on 21 May 1977.[1]

1977 referendum on Senate casual vacancies

This referendum proposed to ensure, as far as practicable, that a casual vacancy in the Senate is filled by a person of the same political party as the Senator chosen by the people, and that the person shall hold the seat for the balance of the term.[1] It resulted in a 73.32% majority vote on 21 May 1977.[1]

1967 referendum on aboriginal people

The 1967 referendum was a landmark decision, enabling the Commonwealth to enact laws for Aboriginal people and remove the prohibition against counting Aboriginal people in population counts in the Commonwealth or a state.[1] The 1967 referendum concerned Section 24 of the Constitution and Section 51 and 127.[10] It carried the largest Yes vote with 90.77% of Australians agreeing to the Australian government including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in population counts.[10]

1910 referendum on finance

This referendum proposed to implement the agreement to allow the Commonwealth to make a fixed payment out of surplus revenue to the States according to population.[1] This was to replace the arrangement where the Commonwealth returned three-quarters of net revenue to the States. It resulted in a 49.04% vote on 13 April 1910.

1911 referendum on legislative powers

This referendum proposed to extend the Commonwealth's powers over trade, commerce, the control of corporations, labour and employment, including wages and conditions; and the settling of disputes; and combinations and monopolies. It resulted in a 39.42% vote on 26 April 1911.[1]

1944 referendum on post-war reconstruction and democratic rights

This referendum proposed to give the Commonwealth power, for a period of five years, to legislate on 14 specific matters, including the rehabilitation of ex-servicemen, national health, family allowances and 'the people of the Aboriginal race.' [2] It was held on 19 August 1944, with a 45.99% result.

1951 referendum on powers to deal with communists and communism

This referendum proposed to give the Commonwealth powers to make laws in respect of communists and communism and was held on 22 September 1951 with a 49.44% voter turnout.[1]

Proposal

Question 1

The 1974 Australian Referendum (Democratic Elections) posed the question: “An Act to alter the Constitution so as to ensure that the members of the House of Representatives and of the parliaments of the states are chosen directly and democratically by the people. Do you approve the proposed law?”

The proposal for the 1974 Australian Referendum (Democratic Elections) was presented to the House of Representatives and was released to Australian voters across all states and territories. This question failed to reach a majority vote. The proposal was accompanied by three other referendum questions.

Question 2

Constitution Alteration (Simultaneous Elections) 1974 aimed to make simultaneous elections compulsory.[11] Proposed law entitled ‘An Act to alter the Constitution so as to ensure that Senate elections are held at the same time as House of Representatives elections’. Do you approve the proposed law?

Question 3

Constitution Alteration (Mode of Altering the Constitution) 1974 aimed to make two alterations to section 128. The first was to provide electors in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory with the right to vote in constitutional referendums.[11] The second was to allow amendments to be made to the Constitution with the approval of a majority of Australian voters and a majority of voters in half the States.[2]

Proposed law entitled ‘An Act to facilitate alterations to the Constitution and to allow electors in territories, as well as electors in the states, to vote at referendums on proposed laws to alter the Constitution’. Do you approve the proposed law?

Question 4

Constitution Alteration (Local Government Bodies) 1974 sought to give the Commonwealth Parliament powers to borrow money for, and to make financial assistance grants directly to, any local government body.[11] Proposed law entitled ‘An Act to alter the Constitution to enable the Commonwealth to borrow money for, and to grant financial assistance to, local government bodies’. Do you approve the proposed law?

Results

The results of the Referendum are calculated by dividing the total of formal and informal votes by the total enrolment figure.[1] The final enrolment figure is the sum number of people who are entitled to vote in a referendum.[12] Rejected declaration votes are not included in the voter turnout totalling.[12]

The 1974 Australian Referendum (Democratic Elections) was an uncarried result, along with proposed question 2, 3 and 4.

Public debate

There has been significant debate about the results of the 1974 Australian Referendum and the implications of it being unsuccessful. The failure of the 1971 Australian Referendum (Democratic Elections) proposal to reach a double majority raised questions about the strength of democracy in Australia’s parliamentary and electoral systems.[13][1]

The proposal to enable people rather than geographic size as the determinant for the size of electorates was a goal to increase democratic processes. While the 1974 voter turnout did not indicate a lack of desire for an effective democratic design for electoral systems, it raised debate about democratic satisfaction in Australia.[13] The series of four questions in the 1974 Australian Referendum also sparked scholarly discussions about voter volatility and uncertainty in referendum voting behaviour, unlike in elections.[14]

The view that political information is limited during referendum processes has been supported by various political scholars.[13] The lack of information and resources available preceding referendums have been discussed by political scholars as contributing to lower percentage of voter approval.[14] McGrath (2012) and DeLuc (2020) discuss the manner in which referendums receive limited media coverage and are less politicised, resulting in a limited dialogue about the subject of referendums and the implications of the possibility of a majority vote and or an uncarried referendum.[13][14] There are views that limited media coverage and the depoliticised nature of referendums has led to poor voter knowledge, and that this can create a reluctance to vote, and to vote intentionally.[14]

References

- Australian Electoral Commission. "Referendum dates and results". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- Australian Electoral Commission. "Referendum dates and results". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- corporateName=Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, Canberra. "4. The crisis of 1974-75". www.aph.gov.au. Retrieved 8 November 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- National Archives of Australia (2017). "Gough Whitlam: Timeline". National Archives of Australia.

- "Whitlam government minister Al Grassby dies". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 April 2005. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- "Referendums and plebiscites - Parliamentary Education Office". peo.gov.au. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- National Archives of Australia (1916–1917). https://www.naa.gov.au/search?search_api_fulltext=1916+referendum. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - National Archives of Australia. https://www.naa.gov.au/search?search_api_fulltext=1916+referendum. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - corporateName=Australian Electoral Commission; address=10 Mort Street, Canberra ACT 2600; contact=13 23 26. "Referendum dates and results". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 24 November 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Miles, Melissa (5 August 2020), "Photography, Aboriginal Rights and the 1967 Australian Referendum", Photography and Its Publics, Routledge, pp. 105–125, doi:10.4324/9781003103721-9, ISBN 978-1-003-10372-1, retrieved 17 November 2020

- "Australia. Referendum, 1974 | Electoral Geography 2.0". Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- corporateName=Australian Electoral Commission; address=10 Mort Street, Canberra ACT 2600; contact=13 23 26. "Referendums". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 8 November 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- McGrath, Michael (September 2012). "Election reform and voter turnout: A review of the history". National Civic Review. 101 (3): 38–43. doi:10.1002/ncr.21086.

- LeDuc, Lawrence (2002), "Referendums and elections", Do Political Campaigns Matter?, Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis, pp. 145–162, doi:10.4324/9780203166956_chapter_9, ISBN 978-0-203-28221-2, retrieved 8 November 2020