9 Metis

Metis (minor planet designation: 9 Metis) is one of the larger main-belt asteroids. It is composed of silicates and metallic nickel-iron, and may be the core remnant of a large asteroid that was destroyed by an ancient collision.[8] Metis is estimated to contain just under half a percent of the total mass of the asteroid belt.[9]

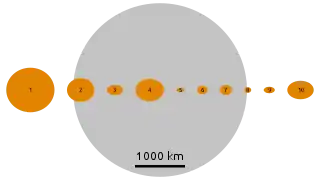

.png.webp) Lightcurve-based 3D-model of Metis | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | A. Graham |

| Discovery date | 25 April 1848 |

| Designations | |

| (9) Metis | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈmiːtɪs/[1] |

Named after | Mētis |

| 1974 QU2 | |

| Main belt | |

| Adjectives | Metidian /mɛˈtɪdiən/ |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| Epoch 14 July 2004 (JD 2453200.5) | |

| Aphelion | 400.548 Gm (2.678 AU) |

| Perihelion | 313.556 Gm (2.096 AU) |

| 357.052 Gm (2.387 AU) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.122 |

| 1346.815 d (3.69 a) | |

| 274.183° | |

| Inclination | 5.576° |

| 68.982° | |

| 5.489° | |

| Proper orbital elements[3] | |

Proper semi-major axis | 2.3864354 AU |

Proper eccentricity | 0.1271833 |

Proper inclination | 4.6853629° |

Proper mean motion | 97.638314 deg / yr |

Proper orbital period | 3.68708 yr (1346.705 d) |

Precession of perihelion | 38.754973 arcsec / yr |

Precession of the ascending node | −41.998090 arcsec / yr |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | (222×182×130) ±12 km[4] 190 km (Dunham)[2] |

| Mass | (1.13±0.22)×1019 kg[lower-alpha 1][4] |

Mean density | 4.12±1.17 g/cm3[4] |

| 0.2116 d (5.079 h)[2] | |

| 0.118[2] | |

| Temperature | max: 282 K (+9 °C)[5] |

| S [6] | |

| 8.1[7] to 11.83 | |

| 6.28[2] | |

| 0.23" to 0.071" | |

Metis passed within 0.034AU, or 5,000,000 kilometres (3,100,000 mi), of Vesta on 19 August 2004.[10]

Discovery and naming

Metis was discovered by Andrew Graham on 25 April 1848, at Markree Observatory in Ireland; it was his only asteroid discovery.[11] It also has been the only asteroid to have been discovered as a result of observations from Ireland until 7 October 2008, when, 160 years later, Dave McDonald from observatory J65 discovered (281507) 2008 TM9.[12] Its name comes from the mythological Metis, a Titaness and Oceanid, daughter of Tethys and Oceanus.[13] The name Thetis was also considered and rejected (it would later devolve to 17 Thetis).

Characteristics

Metis' direction of rotation is unknown at present, due to ambiguous data. Lightcurve analysis indicates that the Metidian pole points towards either ecliptic coordinates (β, λ) = (23°, 181°) or (9°, 359°) with a 10° uncertainty.[14] The equivalent equatorial coordinates are (α, δ) = (12.7 h, 21°) or (23.7 h, 8°). This gives an axial tilt of 72° or 76°, respectively.

Hubble Space Telescope images[15][16] and lightcurve analyses[14] are in agreement that Metis has an irregular elongated shape with one pointed and one broad end.[14][16] Radar observations suggest the presence of a significant flat area,[17] in agreement with the shape model from lightcurves.

The Metidian surface composition has been estimated as 30–40% metal-bearing olivine and 60–70% Ni-Fe metal.[8]

Light curve data on Metis led to an assumption that it could have a satellite. However, subsequent observations failed to confirm this.[18][19] Later searches with the Hubble Space Telescope in 1993 found no satellites.[16]

Family relationships

Metis was once considered to be a member of an asteroid family known as the Metis family,[20] but more recent searches for prominent families did not recognize any such group, nor is a clump evident in the vicinity of Metis by visual inspection of proper orbital element diagrams.

However, a spectroscopic analysis found strong spectral similarities between Metis and 113 Amalthea, and it is suggested that these asteroids may be remnants of a very old (at least ~1 Ga) dynamical family whose smaller members have been pulverised by collisions or perturbed away from the vicinity. The putative parent body is estimated to have been 300 to 600 km in diameter (Vesta-sized) and differentiated.[8] Metis would be the relatively intact core remnant (though smaller than 16 Psyche), and Amalthea a fragment of the mantle, with 90% of the original body unaccounted for.[8] Coincidentally, both Metis and Amalthea have namesakes among Jupiter's inner moons.

Occultations

In 1984 an occultation of a star produced seven chords that Kristensen used to derive an ellipsoidal profile of 210×170 km.[21] On 6 August 1989, Metis occulted a magnitude 8.7 star producing five chords suggesting a diameter of 173.5 km.[21] Observations of an occultation on 11 February 2006, produced only two chords indicating a minimum diameter 156 km.[22] All three of these occultations fit the ellipsoid 222×182×130 km suggested by Baer.[9]

On 7 March 2014, Metis occulted the star HIP 78193 (magnitude 7.9) over parts of Europe and the Middle East.[23][24]

Notes

- 5.7 ± 1.1) × 10−12 M☉

References

- Noah Webster (1884) A Practical Dictionary of the English Language

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 9 Metis" (last observation: 9 September 2008). Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- "AstDyS-2 Metis Synthetic Proper Orbital Elements". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- James Baer, Steven Chesley & Robert Matson (2011) "Astrometric masses of 26 asteroids and observations on asteroid porosity." The Astronomical Journal, Volume 141, Number 5

- L. F. Lim et al., Thermal infrared (8–13 µm) spectra of 29 asteroids: the Cornell Mid-Infrared Asteroid Spectroscopy (MIDAS) Survey, Icarus Vol. 173, p. 385 (2005).

- asteroid lightcurve data file (March 2001)

- Donald H. Menzel & Jay M. Pasachoff (1983). A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 391. ISBN 0-395-34835-8.

- Kelley, Michael S; Michael J. Gaffey (2000). "9 Metis and 113 Amalthea: A Genetic Asteroid Pair". Icarus. 144 (1): 27–38. Bibcode:2000Icar..144...27K. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6266.

- Jim Baer (2010). "Recent Asteroid Mass Determinations". Personal Website. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "JPL Close-Approach Data: 9 Metis". 15 March 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- Graham, A.; New Planet, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 6 (dated 14 April 1848!), p. 146 (signed 29 April 1848; the discovery was first announced on 27 April)

- "Amateur Astronomer Becomes Second Ever to Discover Asteroid from Ireland, After 160 Years". International Year of Astronomy in Ireland. 10 October 2008. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- Graham, A.; Metis, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 7 (dated 12 May 1848), pp. 147–150

- J. Torppa et al., Shapes and rotational properties of thirty asteroids from photometric data, Icarus Vol. 164, p. 346 (2003).

- A. D. Storrs et al., A closer look at main-belt asteroids 1: WF/PC images, Icarus Vol. 173, p. 409 (2005).

- Hubble Space Telescope observations Archived 30 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- D. L. Mitchell et al., Radar Observations of Asteroids 7 Iris, 9 Metis, 12 Victoria, 216 Kleopatra, and 654 Zelinda, Icarus Vol. 118, p. 105 (1995).

- research at IMCCE Archived 12 June 2002 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- "other" reports of asteroid companions

- J. G. Williams, Asteroid Families – An Initial Search, Icarus Vol. 96, p. 251 (1992).

- Kissling, W.M; Blow, G. L.; Allen, W. H.; Priestley, J.; Riley, P.; Daalder, P.; George, M. (1991). "The Diameter of 9 Metis from the Occultation of SAO:190531". Proceedings of the Astronomical Society of Australia. 9: 150–152. Bibcode:1991PASAu...9..150K. doi:10.1017/S1323358000025352.

- "Occultation of TYC 0862-00695-1 by (9) Metis 2006 February 11". Royal Astronomical Society of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2008. (Chords) Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Asteroid Occulations Archived 6 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Map Archived 6 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- shape model deduced from lightcurve

- "Notice of discovery of Metis", MNRAS 8 (1848) 146

- Irish Astronomical History: Markree Castle Observatory and The Discovery of the Asteroid Metis

- JPL Ephemeris

- "Elements and Ephemeris for (9) Metis". Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. (displays Elong from Sun and V mag for 2011)

- Globe of 9 Metis

- 9 Metis at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 9 Metis at the JPL Small-Body Database