Abatur

Abatur (Classical Mandaic: ࡀࡁࡀࡕࡅࡓ, sometimes called Abathur; Yawar, Classical Mandaic: ࡉࡀࡅࡀࡓ; and the Ancient of Days) is the second of three emanations of the Mandaean God Hayyi Rabbi (Classical Mandaic: ࡄࡉࡉࡀ ࡓࡁࡉࡀ, “The Great Living God”) in the Mandaean religion. His name translates as the “father of the Uthre”, the Mandaean name for celestial beings. His usual epithet is the Ancient (Atiga) and he is also called the deeply hidden and guarded. He is described as being the son of the first emanation, or Yoshamin (Classical Mandaic: ࡉࡅࡔࡀࡌࡉࡍ).[1]

He exists in two different personae. These include Abatur Rama (Classical Mandaic: ࡀࡁࡀࡕࡅࡓ ࡓࡀࡌࡀ, the "lofty" or celestial Abatur), and his "lower" counterpart, Abatur of the Scales (Classical Mandaic: ࡀࡁࡀࡕࡅࡓ ࡌࡅࡆࡀࡍࡉࡀ, romanized: Abatur Muzania), who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate.

Abatur in Diwan Abatur

He is one of the main characters in the book the Diwan Abatur, one of the more recent texts of the Mandaeans. The text begins with a lacuna. He is said to reside on the borderland between the here and the hereafter, at the farthest verge of the Worlds of Light that lies toward the lower regions. Beneath him was originally nothing but a huge void with muddy black water at the bottom, in which his image was reflected.[1] The existing text starts with Hibil Ziwa (Classical Mandaic: ࡄࡉࡁࡉࡋ ࡆࡉࡅࡀ, an important Lightworld envoy) telling Abatur to go and reside in the boundary between the Worlds of Light and the Worlds of Darkness, and weigh for purity those souls which have passed through all the purgatories and wish to return to the light. Abatur is not happy with the assignment, complaining that he is being asked to leave his home and his wives and do this task. Abatur then rather impatiently asks a whole series of questions regarding specific sins of omission and sins of commission, asking in effect how can such impure souls be saved. Hibil Ziwa then answers these questions in a rather lengthy response.

In a later section of the book, it is revealed that Abatur is the source of Ptahil (Classical Mandaic: ࡐࡕࡀࡄࡉࡋ), who is the demiurge in Mandaean mythology. The book indicates how Abatur gives Ptahil precise instructions on how to create the universe (Classical Mandaic: ࡕࡉࡁࡉࡋ, romanized: Tibil) in the void described above, and gives him the materials and help (in the form of demons from the World of Darkness) he needs to do so. Ptahil, like Abatur before him, complains about his assignment, but does as he is told. The world he creates is a very dark place, unlike the Worlds of Light from which Abatur and the others come from.

After the world is created, the Adam of the Mandaeans asks Abatur what he will do when he goes to Earth. Abatur answers that Adam will be helped by Manda d'Hayyi, the entity which instructs humans with sacred knowledge and protects them. This enrages Ptahil, who dislikes Abatur giving a degree of control of his own creatures to someone else, and complains bitterly about it, in much the same way that Abatur had complained about his assignment to Hibil Ziwa.

He subsequently serves in his capacity as judge of the dead, in much the same capacity as Rashnu and Anubis. Those souls which qualify can enter into the World of Light from which Abatur himself came. He himself will only be allowed to return to the World of Light by Hibil Ziwa upon the end of the poorly made universe Ptahil created.

Imagery

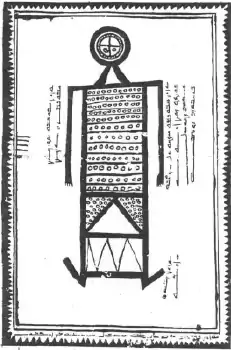

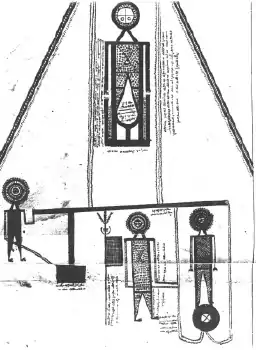

Images of the Mandaean beings tend to be of a blocky style vaguely reminiscent of European cubism, and this imagery, allowing for stylistic differences of individual artists, is consistent throughout the illustrated diwans. None of the celestial beings shown has any fleshy or material bodies, and this may play a part in the non-representative nature of their depictions. In the surviving images in the Diwan Abatur, Abatur is depicted sitting on a throne. Both Abatur and Ptahil are depicted as having faces divided into quarters, with what seem to be eyes in the lower two quarters of the face. Some have interpreted this as indicating that they both have to look down upon the earth.

Notes

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mandaeans". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 555–556.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mandaeans". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 555–556.