Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ashʿath (Arabic: عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن الأشعث), commonly known as Ibn al-Ashʿath after his grandfather [1] Muhammad ibn al-Ashath. He was a distinguished Arab nobleman and general during the Umayyad Caliphate, most notable for leading a failed rebellion against the Umayyad viceroy of the east, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, in 700–703.

Abd al-Rahman ibn al-Ash'ath | |

|---|---|

| Died | 704 Rukhkhaj |

| Allegiance | Umayyad Caliphate |

| Years of service | 680–700 |

| Battles/wars | Campaign against al-Mukhtar, Umayyad campaigns against Shabib ibn Yazid al-Shaybani and the Zunbīl |

| Relations |

|

The scion of a distinguished family of the Kindaite tribal nobility, he played a minor role in the Second Fitna (680–692) and then served as governor of Rayy. Al-Hajjaj was appointed governor of Iraq after he had killed Abdullah ibn Zubayr, the grandson of Abu Bakr, and restored Umayyad rule in Makkah. After the appointment of al-Hajjaj as governor of Iraq and the eastern provinces of the Caliphate in 694, relations between the haughty and overbearing al-Hajjaj and the Iraqi nobility quickly became strained. Nevertheless, in 699 or 700, al-Hajjaj appointed Ibn al-Ash'ath as commander of a huge Iraqi army, the so-called "Peacock Army", to subdue the troublesome principality of Zabulistan, whose ruler, the Zunbīl, vigorously resisted Arab expansion. During the campaign, al-Hajjaj's overbearing behaviour caused Ibn al-Ash'ath and the army to rebel. After patching up an agreement with the Zunbīl, the army started on its march back to Iraq. On the way, a mutiny against al-Hajjaj developed into a full-fledged anti-Umayyad rebellion.

Al-Hajjaj initially retreated before the rebels' superior numbers, but quickly defeated and drove them out of Basra. Nevertheless, the rebels seized Kufa, where supporters started flocking. The revolt gained widespread support among those who were discontented with the Umayyad regime, especially the religious scholars known as qurrāʾ ("Quran readers"). Caliph Abd al-Malik tried to negotiate terms, including the dismissal of al-Hajjaj, but the hardliners among the rebel leadership pressured Ibn al-Ash'ath into rejecting the Caliph's terms. In the subsequent Battle of Dayr al-Jamajim, the rebel army was decisively defeated by al-Hajjaj's Syrian troops. Al-Hajjaj pursued the survivors, who under Ibn al-Ash'ath fled to the east. Most of the rebels were captured by the governor of Khurasan, while Ibn al-Ash'ath himself fled to Zabulistan. His fate is unclear, as some accounts hold that, after long pressure from al-Hajjaj to surrender him, the Zunbīl executed him, while most sources claim that he committed suicide to avoid being handed over to his enemies.

The suppression of Ibn al-Ash'ath's revolt signalled the end of the power of the tribal nobility of Iraq, which henceforth came under the direct control of the Umayyad regime's staunchly loyal Syrian troops. Later revolts, under Yazid ibn al-Muhallab and Zayd ibn Ali, also failed, and it was not until the success of the Abbasid Revolution that the Syrian dominance of Iraq was broken.

Early life

Origin and family

Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath was a descendant of a noble family from the Kinda tribe in the Hadramawt.[2] His grandfather, Ma'dikarib, better known by his nickname "al-Ash'ath" ("He with the dishevelled hair"), was an important chieftain who submitted to Muhammad, but rebelled during the Ridda wars. Defeated, al-Ash'ath was pardoned and married Caliph Abu Bakr's sister. He went on to participate in the crucial battles of the early Muslim conquests, Yarmouk and Qadisiyya, as well as in the Battle of Siffin, where he was instrumental in forcing Ali to abandon his military advantage and submit to arbitration, and later led the Kindaite quarter in Kufa, where he died in 661.[3][4][5]

Abd al-Rahman's father, Muhammad, was far less distinguished, serving an unsuccessful tenure as Umayyad governor of Tabaristan, and becoming involved in the Second Fitna as a supporter of the anti-Umayyad rebel Ibn al-Zubayr, being killed in 686/7 in the campaign that overthrew al-Mukhtar. Like his father at Siffin, he is denigrated by pro-Alid sources for his ambiguous role in the Battle of Karbala in 680, being held responsible for the arrests of Muslim ibn Aqil and Hani ibn Urwa.[5][6]

Ibn al-Ash'ath's mother, Umm Amr, was the daughter of Sa'id ibn Qays al-Hamdani.[2] Ibn al-Ash'ath had four brothers, Ishaq, Qasim, Sabbah, and Isma'il, of whom the first three also fought in the campaigns in Tabaristan.[7]

Early career

According to the historian al-Tabari, the young Ibn al-Ash'ath accompanied his father and participated in his political activities: in 680 he revealed the hiding-place of Muslim ibn Aqil to the authorities.[2] In 686–687, he fought in Mus'ab ibn al-Zubayr's campaign against al-Mukhtar, in which his father was killed.[2][8] After al-Mukhtar was defeated and captured, along with the other Kufan ashrāf (the Arab tribal nobility) who served under Mus'ab, Ibn al-Ash'ath urged the execution of al-Mukhtar and his followers. This was not only to avenge the loss of their own kinsmen during the campaign, but also because of the deeply ingrained hostility of the ashrāf to the non-Arab converts to Islam (the mawālī), who had formed the bulk of al-Mukhtar's supporters. As a result, both al-Mukhtar and some 6,000 of his men were executed.[2][9]

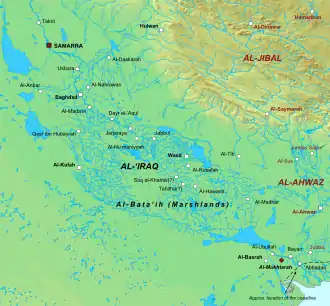

Ibn al-Ash'ath disappears from the record during the next few years, but after Mus'ab was defeated and killed by the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan at the Battle of Maskin in October 691, he, like other followers of Mus'ab, apparently went over to the Umayyads.[2] In early 692, he participated in a campaign against the Kharijites in al-Ahwaz, at the head of 5,000 Kufan troops. After the Kharijites were defeated, he went on to take up the governorship of Rayy.[2][10]

Expedition against Shabib al-Shaybani

Muslim state at the death of Muhammad Expansion under the Rashidun Caliphate Expansion under the Umayyad Caliphate

In 694, Abd al-Malik appointed the trusted and capable al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf as the new governor of Iraq, a crucial post given the restiveness of the region towards Umayyad rule. In 697, his remit was expanded to cover the entirety of the eastern Caliphate, including Khurasan and Sistan.[11][12]

In late 695, al-Hajjaj entrusted Ibn al-Ash'ath with 6,000 horsemen and the campaign against the Kharijite rebels under Shabib ibn Yazid al-Shaybani. Although the Kharijites numbered just a few hundred, they benefited from Shabib's tactical skill and had defeated every Umayyad commander sent against them thus far.[2][13] Advised by the general al-Jazl Uthman ibn Sa'id al-Kindi, who had been defeated by Shabib previously,[14] Ibn al-Ash'ath pursued the Kharijites, but displayed great caution in order to avoid falling into a trap. Notably, each night he dug a trench around his camp, thus foiling Shabib's plans to launch a surprise night attack. Unable to catch Ibn al-Ash'ath unawares, Shabib instead resolved to wear down his pursuers, by retreating before them into barren and inhospitable terrain, waiting for them to catch up, and retreating again.[15]

As a result, the governor of al-Mada'in, Uthman ibn Qatan, wrote to al-Hajjaj criticizing Ibn al-Ash'ath's leadership as timid and ineffective. Al-Hajjaj responded by giving command to Uthman, but when the latter attacked Shabib on 20 March 696, the Umayyad army suffered a heavy defeat, losing around 900 men and fleeing to Kufa. Uthman himself was killed, while Ibn al-Ash'ath, who lost his horse, managed to escape with the help of a friend and reached Kufa after an eventful journey. Fearing reprisals for the defeat by al-Hajjaj, he remained in hiding until the governor of Iraq granted him pardon.[2][16]

Rivalry with al-Hajjaj

Despite this setback, relations between Ibn al-Ash'ath and al-Hajjaj were initially friendly, and al-Hajjaj's son married one of Ibn al-Ash'ath's sisters.[2] Gradually, however, the two men became estranged. The sources attribute this to Ibn al-Ash'ath's overweening pride as one of the foremost of the ashrāf, and his aspirations to leadership: al-Mas'udi records that he adopted the title of Nāṣir al-muʾminīn ("Helper of the Faithful"), an implicit challenge to the Umayyads, who were implied to be false believers.[2] In addition, he claimed to be the Qaḥṭānī, a messianic figure in South Arab ("Yamani") tribal tradition who was expected to raise them to domination.[2]

Ibn al-Ash'ath's pretensions irked al-Hajjaj, whose hostile remarks—such as "Look how he walks! How I should like to cut off his head!"—were conveyed to Ibn al-Ash'ath and served to deepen their hostility to outright mutual hatred.[2] According to Laura Veccia Vaglieri, however, these reports are more indicative of the Arabic sources' tendency to "explain historical events by incidents relating to persons", rather than the actual relationship between the two men, especially given the fact that Ibn al-Ash'ath faithfully served al-Hajjaj in a number of posts, culminating in his appointment to lead the "Peacock Army".[17]

Nevertheless, it is clear that al-Hajjaj quickly became unpopular among the Iraqis in general through a series of measures that, according to Hugh N. Kennedy, "[seem] almost to have goaded the Iraqis into rebellion", such as the introduction of Syrian troops—the mainstay of the Umayyad dynasty—into Iraq, the use of Iraqi troops in the arduous and unrewarding campaigns against the Kharijites, and the reduction of the Iraqi troops' pay to a level below that of the Syrian troops.[18][19]

Revolt

Sistan campaign

In 698/9, the Umayyad governor of Sistan, Ubayd Allah ibn Abi Bakra, suffered a severe defeat by the semi-independent ruler of Zabulistan, known as the Zunbīl. The Zunbīl drew the Arabs deep into his country and cut them off, so that they managed to extricate themselves only with great difficulty and after suffering many losses, particularly among the Kufan contingent.[2][18][20]

In response, al-Hajjaj sent an Iraqi army to the east against the Zunbīl. Whether due to the splendour of its equipment or as an allusion to the "proud and haughty manner of the Kufan soldiers and ashrāf who composed it" (G. R. Hawting), this army became known in history as the "Peacock Army". Two different generals were appointed by al-Hajjaj in succession to command it, before he appointed Ibn al-Ash'ath instead.[18][21] In view of their bad relations, the sources report, the appointment came as a surprise to many; an uncle of Ibn al-Ash'ath even approached al-Hajjaj and suggested that his nephew might revolt, but al-Hajjaj did not rescind his appointment.[22] Al-Tabari suggests that al-Hajjaj relied on the fear he inspired to keep Ibn al-Ash'ath in check. Modern scholarship on the other hand holds that the portrayal of the great personal animosity between the two men is likely to be exaggerated.[17]

Reply of the soldiers to Ibn al-Ash'ath regarding al-Hajjaj's orders[23]

It is unclear whether Ibn al-Ash'ath himself had joined the army from the outset or whether, according to an alternative tradition, he had originally been sent to Kirman to punish a local leader who had refused to help the governors of Sistan and Makran.[22] After taking up the leadership of the army, Ibn al-Ash'ath led it to Sistan, where he united the local troops with the "Peacock Army". He rejected a peace offer from the Zunbīl and—in marked contrast to his predecessor's direct assault—began a systematic campaign to first secure the lowlands surrounding the mountainous heart of the Zunbīl's kingdom: slowly and methodically, he captured the villages and fortresses one by one, installing garrisons in them and linking them with messengers. After accomplishing this task, he withdrew to Bust to spend the winter of 699/700.[22]

Outbreak of the revolt

Once al-Hajjaj received Ibn al-Ash'ath's messages informing him of the break in operations, he replied in what Veccia Vaglieri described as "a series of arrogant and offensive messages ordering him to penetrate into the heart of Zabulistan and there to fight the enemy to the death". Ibn al-Ash'ath called an assembly of the army's leadership, in which he informed them of al-Hajjaj's orders for an immediate advance and his decision to refuse to obey. He then went before the assembled troops and repeated al-Hajjaj's instructions, calling upon them to decide what should be done. The troops clearly resented "the prospect of a long and difficult campaign so far from Iraq" (Hawting), denounced al-Hajjaj, proclaiming him deposed, and swore allegiance to Ibn al-Ash'ath instead.[22][24] Ibn al-Ash'ath's brothers, however, as well as the governor of Khurasan, al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra, refused to join the rebellion.[25]

Ibn al-Ash'ath hastily concluded an agreement with the Zunbīl, whereby if he was victorious in the coming conflict with al-Hajjaj, he would accord the Zunbīl generous treatment, while if he was defeated, the Zunbīl would provide refuge.[22] With his rear secure, Ibn al-Ash'ath left representatives at Bust and Zaranj, and his army set out on the return journey to Iraq, picking up more soldiers from Kufa and Basra, who were stationed as garrisons, along the way.[22][26]

By the time the army reached Fars, it had become clear that deposing al-Hajjaj could not be done without deposing Caliph Abd al-Malik as well, and the revolt evolved from a mutiny into a full-blown anti-Umayyad uprising, with the troops renewing their oath of allegiance (bayʿa) to Ibn al-Ash'ath.[22][26]

Motives and driving forces of the revolt

The reasons for the rebellion have been the source of much discussion and theories among modern scholars. Moving away from the personal relationship between al-Hajjaj and Ibn al-Ash'ath, Alfred von Kremer suggested that the rebellion was linked with the efforts of the mawālī to secure equal rights with the Arab Muslims. Julius Wellhausen rejected this view as the main source of the revolt, seeing it instead as a reaction of the Iraqis in general and the ashrāf in particular against the Syrian-dominated regime of the Umayyads as represented by the overbearing (and notably low-born) al-Hajjaj.[17][27]

Other scholars have seen in it a manifestation of the intense tribal factionalism between the northern Arab and southern Arab ("Yamani") tribal groups prevalent at the time.[28] Thus a poem by a certain A'sha Hamdan in celebration of the rebellion shows not only a religious but also a tribal motivation of the rebel troops: al-Hajjaj is denounced as an apostate and a "friend of the devil", while Ibn al-Ash'ath is portrayed as the champion of the Yamani Qahtani and Hamdani tribes against the northern Arab Ma'addis and Thaqafis.[22] On the other hand, as Hawting points out, this is insufficient evidence to ascribe purely tribal motivations to the revolt: if Ibn al-Ash'ath's movement was indeed led largely by Yamanis, this simply reflects the fact that they were the dominant element in Kufa, and while al-Hajjaj himself was a northerner, his main commander was a southerner.[28] Furthermore, Hawting points out that Wellhausen's analysis ignored the evident religious dimension of the revolt, especially the participation of the militant zealots known as qurrāʾ ("Quran readers"). While the "religious polemic used by both sides [..] is stereotyped, unspecific and to be found in other contexts", according to Hawting, there do appear to have been specific religious grievances, notably the accusation that the Umayyads were neglecting the ritual prayer. It seems that the revolt began as a simple mutiny against an overbearing governor who made impossible demands of the troops, but, at least by the time the army reached Fars, a religious element had emerged, represented by the qurrāʾ. Given the close "interaction of religion and politics in early Muslim society" (Hawting), the religious element quickly became dominant, as seen by the difference between the bayʿa sworn at the beginning of the revolt and that exchanged between the army and Ibn al-Ash'ath at Istakhr in Fars. While in the first Ibn al-Ash'ath declared as his intention to "depose al-Hajjaj, the enemy of God", in the latter, he exhorted his men to "[defend] the Book of God and the Sunna of His Prophet, to depose the imāms of error, to fight against those who regard [the blood of the Prophet’s kin] as licit".[17][29]

Although Ibn al-Ash'ath remained as the head of the uprising, Veccia Vaglieri suggests that after this point "one has the impression that [...] the control of the revolt slipped from his hands", or that, as Wellhausen comments, "he was urged on in spite of himself, and even if he would, could not have banished the spirits which he had called up. It was as if an avalanche came rushing down sweeping every thing before it".[26][17] This interpretation is corroborated by the different rhetoric and actions of Ibn al-Ash'ath and his followers, as reported in the sources: the former was ready and willing to compromise with the Umayyads, and continued to fight only because he had no alternative, while the great mass of his followers, motivated by discontent against the Umayyad regime couched in religious terms, were far more uncompromising and willing to carry on the struggle until death.[30] Al-Hajjaj himself seems to have been aware of the distinction: in suppressing the revolt, he pardoned the Quraysh, the Syrians, and many of the other Arab clans, but executed tens of thousands among the mawālī and the Zutt of the Mesopotamian Marshes, who had sided with the rebels.[31]

Fight for control of Iraq

Informed of the revolt, al-Hajjaj requested reinforcements from the Caliph, but was unable to stop the advance of the rebel army, which is reported to have numbered 33,000 cavalry and 120,000 infantry. On 24 or 25 January 701, Ibn al-Ash'ath overwhelmed al-Hajjaj's advance guard at Tustar. At the news of this defeat, al-Hajjaj withdrew to Basra and then, as he could not possibly hold the city, left it as well for nearby al-Zawiya.[22] Ibn al-Ash'ath entered Basra on 13 February 701. Over the next month, a series of skirmishes were fought between the forces of Ibn al-Ash'ath and al-Hajjaj, in which the former generally held the upper hand. Finally, in early March, the two armies met for a pitched battle. Ibn al-Ash'ath initially prevailed, but in the end al-Hajjaj's Syrians, under Sufyan ibn al-Abrad al-Kalbi, carried off a victory. Many rebels fell, especially among the qurrāʾ, forcing Ibn al-Ash'ath to withdraw to Kufa, taking with him the Kufan troops and the élite of the Basran cavalry.[22][32] At Kufa, Ibn al-Ash'ath found the citadel occupied by Matar ibn Najiya, an officer from al-Mada'in, and was forced to take it by assault.[22][33]

His lieutenant at Basra, the Hashimi Abd al-Rahman ibn Abbas, tried but was unable to hold the city, as the populace opened the gates in exchange for a pardon after a few days. Abd al-Rahman too withdrew with as many Basrans as would follow him to Kufa, where Ibn al-Ash'ath's forces swelled further with the arrival of large numbers of anti-Umayyad volunteers.[22] After taking control of Basra—and executing some 11,000 of its people, despite his pledge of pardon—al-Hajjaj marched on Kufa in April 701. His army was harassed by Ibn al-Ash'ath's cavalry, but reached the environs of the city and set up camp at Dayr Qurra, on the right bank of the Euphrates so as to secure his lines of communication with Syria. In response Ibn al-Ash'ath left Kufa and with an army reportedly 200,000 strong approached al-Hajjaj's army and set up camp at Dayr al-Jamajim. Both armies fortified their camps by digging trenches and, as before, engaged in skirmishes. Whatever the true numbers of Ibn al-Ash'ath's force, al-Hajjaj was in a difficult position: although reinforcements from Syria were constantly arriving, his army was considerably outnumbered by the rebels, and his position was difficult to resupply with provisions.[34][35]

In the meantime, Ibn al-Ash'ath's progress had sufficiently alarmed the Umayyad court that they sought a negotiated settlement, despite the contrary advice of al-Hajjaj. Caliph Abd al-Malik sent his brother Muhammad and son Abdallah as envoys, proposing the dismissal of al-Hajjaj, the appointment of Ibn al-Ash'ath as governor over one of the Iraqi towns, and a raise in the Iraqis' pay so that they received the same amount as the Syrians. Ibn al-Ash'ath was inclined to accept, but the more radical of his followers, especially the qurrāʾ, refused, believing that the offered terms revealed the government's weakness, and pushed for outright victory.[19][36][37] With the negotiations failing, the two armies continued to skirmish—the sources report that the skirmishing lasted for 100 days with 48 engagements. This lasted until September, when the two armies met in battle. Again Ibn al-Ash'ath initially held the upper hand, but the Syrians prevailed in the end: shortly before the sun set, Ibn al-Ash'ath's men broke and scattered. Failing to rally his troops, Ibn al-Ash'ath with a handful of followers fled to Kufa, where he took farewell of his family.[36][38] As Hawting comments, the contrast "between the discipline and organisation of the Umayyads and their largely Syrian support and the lack of these qualities among their opponents in spite of, or perhaps rather because of, the more righteous and religious flavour of the opposition" is a recurring pattern in the civil wars of the period.[39]

Victorious, al-Hajjaj entered Kufa, where he tried and executed many rebels, but also pardoned those who submitted after admitting that through revolt they had become infidels.[36][28] In the meantime, however, one of Ibn al-Ash'ath's supporters, Ubayd Allah ibn Samura, had recaptured Basra, to where Ibn al-Ash'ath now headed; and another, Muhammad ibn Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, had captured al-Mada'in. Al-Hajjaj remained for a month in Kufa, before setting out to meet Ibn al-Ash'ath. The two armies met at Maskin on the river Dujayl. After two weeks of skirmishing, al-Hajjaj delivered the final blow by launching a simultaneous attack on the rebel camp from two sides: while he with the main part of his army attacked from one side, a portion of his army, guided by a shepherd, crossed the marshes and launched itself on the camp from the rear. Caught by surprise, the rebel army was nearly annihilated, with many of its troops drowning in the river in their attempt to flee.[36][40]

Flight east and death

Following this renewed defeat, Ibn al-Ash'ath fled east, towards Sistan, with a few survivors. Al-Hajjaj sent troops under Umara ibn al-Tamim al-Lakhmi to intercept them. Umara caught up with them twice, at Sus and Sabur, but Ibn al-Ash'ath and his men managed to fight through to Kirman and thence to Sistan.[36][41] There he was refused entry into Zaranj by his own agent (ʿāmil), and was then arrested by the ʿāmil of Bust. The Zunbīl however, true to his word, came to Bust and forced Ibn al-Ash'ath's release, taking him with him to Zabulistan and treating him with much honour.[36][41] Ibn al-Ash'ath assumed command of some 60,000 supporters who had assembled there in the meantime. With their support, he seized Zaranj, where he punished the ʿāmil. Faced with the approach of the Umayyad troops under Umara ibn al-Tamim, however, most of Ibn al-Ash'ath's followers urged him to go to Khurasan, where they would be hopefully able to recruit more followers, and sit out the Umayyad attacks until either al-Hajjaj or Caliph Abd al-Malik died and the political situation changed. Ibn al-Ash'ath bowed to their pressure, but after a group of 2,000 men defected, he returned to Zabulistan with those who would follow him there.[36][42] Most of the rebels remained in Khurasan, choosing Abd al-Rahman ibn Abbas as their leader. They were soon confronted and defeated by the local governor, Yazid ibn al-Muhallab. Yazid released those who belonged to the Yamani tribes related to his own, and sent the rest to al-Hajjaj, who executed most of them.[36][43] In the meantime, Umara quickly effected the surrender of Sistan, by offering lenient terms to the garrisons if they surrendered without struggle.[43]

Ibn al-Ash'ath remained safe under the protection of the Zunbīl, but al-Hajjaj, fearing that he might raise another revolt, sent letters to the Zunbīl, mixing threats and promises, to secure his surrender. Finally, in 704 the Zunbīl gave in, in exchange for lifting the annual tribute for 7 or 10 years.[36][44] Accounts of Ibn al-Ash'ath's end differ: one version holds that he was executed by the Zunbīl himself, or that he died of illness, and that his head was cut off and sent to al-Hajjaj. The more widespread account, however, holds that he was confined to a remote castle at Rukhkhaj in anticipation of his extradition to al-Hajjaj, and chained to his warden, but that he threw himself from the top of the castle (along with his warden) to his death.[36]

Aftermath

The failure of Ibn al-Ash'ath's revolt led to the tightening of Umayyad control over Iraq. Al-Hajjaj founded a permanent garrison for the Syrian troops at Wasit, situated between Basra and Kufa, and the Iraqis, regardless of social status, were deprived of any real power in the governance of the region.[45] This was coupled with a reform of the salary (ʿaṭāʾ) system by al-Hajjaj: whereas hitherto the salary had been calculated based on the role of one's ancestors in the early Muslim conquests, it now became limited to those actively participating in campaigns. As most of the army was now composed of Syrians, this measure gravely injured the interests of the Iraqis, who regarded this as another impious attack on hallowed institutions.[45] In addition, extensive land reclamation and irrigation works were undertaken in lower Iraq (the Sawad), but this was limited mostly to around Wasit, and the proceeds went to the Umayyads and their clients, not the Iraqi nobility. As a result, the political power of the once mighty Kufan élites was soon broken.[46]

It was not until 720 that the Iraqis rebelled once again, under Yazid ibn al-Muhallab, "the last of the old-style Iraqi champions" (Hugh Kennedy), and even then, support was ambivalent, and the revolt was defeated.[47] Two of Ibn al-Ash'ath's nephews, Muhammad ibn Ishaq and Uthman ibn Ishaq, supported the rebellion, but most remained quiescent and content with their role as local dignitaries. A few held posts in Kufa under the early Abbasids. Perhaps the most famous of the family's later members is the philosopher al-Kindi (c. 801–873).[48] Another uprising, that of Zayd ibn Ali, broke out in 740. Zayd also promised to right injustices (restoration of the ʿaṭāʾ, distribution of the revenue from the Sawad, an end to distant campaigns) and to restore rule "according to the Quran and the Sunna". Once more, the Kufans deserted it at the critical moment, and the revolt was defeated by the Umayyads.[49] Discontent with the Umayyad government continued to simmer, and during the Abbasid Revolution, Iraq rose up in support of the rebellion. Kufa overthrew Umayyad rule and welcomed the Abbasid army in October 749, followed immediately by the proclamation of as-Saffah as the first Abbasid caliph there.[50]

References

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 233.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, p. 715.

- Reckendorf 1960, pp. 696–697.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 54, 56, 77–78.

- Crone 1980, p. 110.

- Hawting 1993, pp. 400–401.

- Crone 1980, pp. 110–111.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 99–100, 106–108.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 115–117.

- Fishbein 1990, pp. 203–204.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 100–101.

- Hawting 2000, p. 66.

- Rowson 1989, pp. xii, 32–81.

- Rowson 1989, pp. 53–63, 81.

- Rowson 1989, pp. 81–84.

- Rowson 1989, pp. 84–90.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, p. 718.

- Hawting 2000, p. 67.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 101.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 231–232.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, pp. 715–716.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, p. 716.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 233–234.

- Hawting 2000, pp. 67–68.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 234–235.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 234.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 243–249.

- Hawting 2000, p. 69.

- Hawting 2000, pp. 68, 69–70.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, pp. 718–719.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, p. 719.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 235–236.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 236.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, pp. 716–717.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 236–237.

- Veccia Vaglieri 1971, p. 717.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 237.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 237–238.

- Hawting 2000, pp. 68–69.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 238–239.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 239.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 239–240.

- Wellhausen 1927, p. 240.

- Wellhausen 1927, pp. 240–241.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 102.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 102–103.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 107–108.

- Crone 1980, p. 111.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 111–112.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 114–115, 127.

Sources

- Crone, Patricia (1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Dixon, 'Abd al-Ameer (1971). The Umayyad Caliphate, 65–86/684–705: (A Political Study). London: Luzac. ISBN 978-0-7189-0149-3.

- Fishbein, Michael, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXI: The Victory of the Marwānids, A.D. 685–693/A.H. 66–73. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0221-4.

- Hawting, G. R. (1993). "Muḥammad b. al-As̲h̲ʿat̲h̲". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 400–401. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hinds, Martin, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIII: The Zenith of the Marwānid House: The Last Years of ʿAbd al-Malik and the Caliphate of al-Walīd, A.D. 700–715/A.H. 81–95. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-721-1.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Reckendorf, H. (1960). "al-As̲h̲ʿat̲h̲". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 696–697. OCLC 495469456.

- Rowson, Everett K., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXII: The Marwānid Restoration: The Caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik, A.D. 693–701/A.H. 74–81. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-975-8.

- Veccia Vaglieri, L. (1971). "Ibn al-As̲h̲ʿat̲h̲". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 715–719. OCLC 495469525.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.