Adipsia

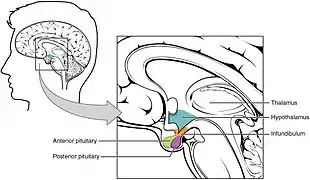

Adipsia, also known as hypodipsia, is a symptom of inappropriately decreased or absent feelings of thirst.[1][2] It involves an increased osmolality or concentration of solute in the urine, which stimulates secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the hypothalamus to the kidneys. This causes the person to retain water and ultimately become unable to feel thirst. Due to its rarity, the disorder has not been the subject of many research studies.

| Adipsia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | hypodipsia |

| |

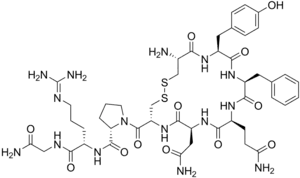

| Molecular structure of vasopressin. This hormone is related to Type A and Type B adipsia. | |

Adipsia may be seen in conditions such as diabetes insipidus[3] and may result in hypernatremia.[4] It can occur as the result of abnormalities in the hypothalamus, pituitary and corpus callosum,[5] as well as following pituitary/hypothalamic surgery.[6]

It is possible for hypothalamic dysfunction, which may result in adipsia, to be present without physical lesions in the hypothalamus, although there are only four reported cases of this.[7] There are also some cases of patients experiencing adipsia due to a psychiatric disease. In these rare psychogenic cases, the patients have normal levels of urine osmolality as well as typical ADH activity.[8]

Cause

Dopamine

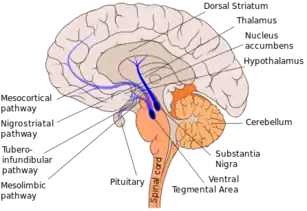

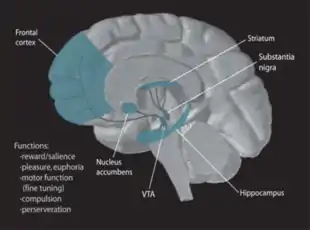

Dopamine, a neurotransmitter, has been linked with feeding behaviors. In an experiment, scientists measured how much food and water mice consumed when they were born without dopamine in their systems. They found that without dopamine, the mice would starve and be dehydrated to the point of death. The scientists then injected the mice without dopamine with its precursor, L-DOPA, and the mice started eating again. But, even though the mice were born without dopamine in their systems, they still had the capacity to control their feeding and drinking behaviors, suggesting that dopamine does not play a role in developing those neural circuits. Instead, dopamine is more closely related to the drive for hunger and thirst. Although the lack of dopamine resulted in adipsia in these rats, low levels of dopamine do not necessarily cause adipsia. [9]

Other findings in support of the role of dopamine in thirst regulation involved the nigrostriatal pathway. After completely degenerating the pathway, the animal becomes adipsic, aphagic, and loses its interest in exploring. Although dopamine plays a role in adipsia, there is no research involving exclusively the relationship between adipsia and dopamine, as changes in dopamine simultaneously mediate changes in eating and curiosity, in addition to thirst.[10]

Hypothalamus

The area of the brain that regulates thirst is located in the anterior part of the hypothalamus. The anterior hypothalamus is in close proximity to osmoreceptors which regulate the secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH). ADH secretion is one of the primary mechanisms by which sodium and osmolar homeostasis are regulated, ADH is also secreted when there are small increases in serum osmolality. Thirst is triggered by increases in serum osmolality and along with increases ADH secretion. Both serum osmolality and ADH maintain normal ranges of serum osmolality.

Adipsia can tend to result from lesions to hypothalamic regions involved in thirst regulation. These lesions can be congenital, acquired, trauma, or even surgery. Lesions or injuries to those hypothalamic regions cause adipsia because the lesions cause defects in the thirst regulating center which can lead to adipsia. Lesions in that region can also cause adipsia because of the extremely close anatomical proximity of the hypothalamus to ADH-related osmoreceptors.[8]

Diagnosis

Symptoms

Diagnosing adipsia can be difficult as there is no set of concrete physical signs that are adipsia specific. Changes in the brain that are indicative of adipsia include those of hyperpnea, muscle weakness, insomnia, lethargy, and convulsions (although uncommon except in extreme cases of incredibly rapid rehydration). Patients with a history of brain tumors, or congenital malformations, may have hypothalamic lesions, which could be indicative of adipsia.[4] Some adults with Type A adipsia are anorexic in addition to the other symptoms.[11]

Testing

Initial testing for adipsia involves electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels, serum and urine osmolality, blood hormone levels, like vasopressin (AVP). In patients who have defects in thirst regulation and vasopresin secretion, serum vassopresin levels are low or absent.[12] Measurements of urine electrolytes and osmolality are critical in determining the central, rather than renal, nature of the defect in water homeostasis. In adipsia, the fractional excretion of sodium is less than 1%, unless a coexisting defect in AVP secretion is present. In salt intoxication, the urine sodium concentrations are very high and fractional excretion of sodium is greater than 1%. Initial test results may be suggestive of diabetes insipidus. The circulating AVP levels tend to be high, which indicate an appropriate response of the pituitary to hyperosmolality. Patients may have mild stable elevations of serum sodium concentrations, along with elevations in both BUN and creatinine levels and in the BUN/creatinine ratio.[4]

Type A

Type A (essential hypernatremia syndrome) involves an increase of the level in which solvent molecules can pass through cell membranes (osmotic threshold) for vasopressin release and the activation of the feeling of thirst. This is the most characterized sub-type of adipsia, however there is no known cause for Type A adipsia. There is debate over whether osmoreceptor resetting could lead to the increase in threshold. Other studies have shown that it is the loss of osmoreceptors, not resetting, that cause the change in threshold.[13] Patients with Type A adipsia can be at risk of seizures if they rapidly re-hydrate or quickly add a significant amount of sodium into their bodies. If not treated, Type A adipsia could result in both a decrease in the size of the brain and bleeding in the brain.[11]

Type B

Type B adipsia occurs when vasopressin responses are at decreased levels in the presence of osmotic stimuli. Although minimal, there is still some secretion of AVP. This type may be due to some elimination of osmoreceptors.[13]

Type C

Type C adipsia (type C osmoreceptor dysfunction) involves complete elimination of osmoreceptors, and as a result have no vasopressin release when there normally would be. Type C is generally the adipsia type found in patients with adipsic diabetes insipidus.[13]

Type D

Type D is the least commonly diagnosed and researched type of adipsia. The AVP release in this subtype occurs with normally functioning levels of osmoregulation.[13]

Management

People affected by adipsia lack the ability to feel thirst, thus they often must be directed to drink. Adipsic persons may undergo training to learn when it is necessary that they drink water. Currently, there is no medicine available to treat adipsia. For people with adipsia because of hypothalamic damage, there is no surgical or medicinal option to fix the damage. In some cases where adipsia was caused by growths on thirst centers in the brain, surgical removal of the growths was successful in treating adipsia. Although adipsic persons must maintain a strict water intake schedule, their diets and participation in physical activities are not limited. People affected by diabetes insipidus have the option of using the intranasal or oral hormone desmopressin acetate (DDAVP), which is molecularly similar enough to vasopressin to perform its function. In this case, desmopressin helps the kidneys to promote reabsorption of water.[4] Some doctors have reported success in treating psychogenic adipsic patients with electroconvulsive therapy, although the results are mixed and the reason for its success is still unknown.[8] Additionally, some patients who do not successfully complete behavioral therapy may require a nasogastric tube in order to maintain healthy levels of fluids.[8]

See also

- Polydipsia - excessive thirst, the opposite of adipsia

- Thirst

- Osmoregulation

References

- "adipsia | pathology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- Lin, M; Liu, SJ; Lim, IT (August 2005). "Disorders of water imbalance". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 23 (3): 749–70, ix. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2005.03.001. PMID 15982544.

- Crowley, R. K.; Sherlock, M.; Agha, A.; Smith, D.; Thompson, C. J. (2007). "Clinical insights into adipsic diabetes insipidus: a large case series". Clinical Endocrinology. 66 (4): 475–82. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02754.x. PMID 17371462.

- Dharnidharka, V.R.; Langman, C.B. (2014). "Adipsia treatment and management". EMedicine.

- Kim, Boo Gyoung; Kim, Ka Young; Park, Youn Jeong; Yang, Keun Suk; Kim, Ji Hee; Jung, Hee Chan; Nam, Hee Chul; Kim, Young Ok; Yun, Yu Seon (2012). "A Case of Adipsic Hypernatremia Associated with Anomalous Corpus Callosum in Adult with Mental Retardation". Endocrinology and Metabolism. 27 (3): 232–6. doi:10.3803/EnM.2012.27.3.232.

- Sherlock, M.; Agha, A.; Crowley, R.; Smith, D.; Thompson, C. J. (2006). "Adipsic diabetes insipidus following pituitary surgery for a macroprolactinoma". Pituitary. 9 (1): 59–64. doi:10.1007/s11102-006-8280-x. PMID 16703410. S2CID 8678093.

- Hayek, A; Peake, GT (1982). "Hypothalamic adipsia without demonstrable structural lesion". Pediatrics. 70 (2): 275–8. PMID 6808452.

- Harrington, C.; Grossman, J.; Richman, K. (2014). "Psychogenic adipsia presenting as acute kidney injury: case report and review of disorders of sodium and water metabolism in psychiatric illness". Psychosomatics. 55 (3): 289–295. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2013.06.013. PMID 24012289.

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Palmiter, R.D. (1995). "Dopamine-deficient mice are severely hypoactive, adipsic, and aphagic". Cell. 83 (7): 1197–1209. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90145-0. PMID 8548806.

- Ungerstedt, U. (2014). "Adipsia and Aphagia after 6-Hydroxydopamine induced degeneration of the nigro-striatal dopamine system". Acta Physiologica. 82(S367): 95–122. doi:10.1111/j.1365-201X.1971.tb11001.x. PMID 4332694.

- Braun, Michael; Barstow, Craig; Pyzocha, Natasha (May 1, 2015). "Diagnosis and management of sodium disorders: Hyponatremia and hypernatremia". American Family Physician. 91 (5): 299–307. PMID 25822386. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- "Adipsia Workup: Laboratory Studies, Imaging Studies, Other Tests". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- Holley, A.D.; Green, S.; Davoren, P. (2007). "Extreme hypernatraemia: a case report and brief review" (PDF). Critical Care and Resuscitation : Journal of the Australasian Academy of Critical Care Medicine. 9 (1): 55–8. PMID 17352668.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |