African-American folktales

African-American folktales are the storytelling and oral history of enslaved African Americans during the 1700-1900s.[1] Many are unique to the African-American culture, while others are influenced by African, European, and Native American tales.[2]

Overview

African-American folktales are a storytelling tradition based in Africa containing a rich oral tradition that expanded as Africans were brought to the Americas as slaves.

In general, most African-American Folktales fall into one of seven categories: tales of origin, tales of trickery and trouble, tales of triumph over natural or supernatural evils, comic heart warming tales, tales teaching life lessons, tales of ghosts and spirits, and tales of slaves and their slave-owners.[2] Many revolve around animals which have human characteristics with the same morals and short comings as humans to make the stories relatable.[3] New tales are based on the experiences of Africans in the Americas, while many of the traditional tales maintain their African roots. Although many of the original stories evolved since African Americans were brought to the Americas as slaves, their meaning and life lessons have remained the same.[1]

Themes

African-American tales of origin center around beginnings and transformations whether focused on a character, event, or creation of the world.[2] Some examples of origin stories includes "How Jackal Became an Outcast" and "Terrapin's Magic Dipper and Whip", that respectively explain the solitary nature of jackals and why turtles have shells.[2]

Trickery and trouble

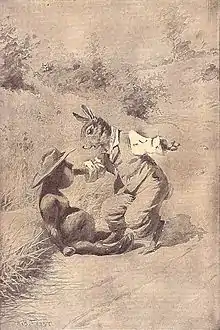

Tricksters in folk stories are commonly amoral characters, both human and non-human animals, who 'succeed' based on deception and taking advantage of the weaknesses of others.[4] They tend to use their wits to resolve conflict and/or achieve their goals. Two examples of African-American tricksters are Brer Rabbit and Anansi.[4]

Tricksters in African American folktales take a comedic approach and contain an underlying theme of inequality.[4] The National Humanities Center notes that trickster stories "contain serious commentary on the inequities of existence in a country where the promises of democracy were denied to a large portion of the citizenry, a pattern that becomes even clearer in the literary adaptations of trickster figures".[4]

The folktales don't always contain an actual 'trickster' but a theme of trickery tactics. For example, Charles Chesnutt's collected a series of stories titled The Conjure Woman (1899).[4] One of the story trickster tactics is "how an enslaved man is spared being sent from one plantation to another by having his wife, who is a conjure woman, turn him into a tree...the trickery works until a local sawmill selects that particular tree to cut".[4]

During the period of slavery, "and for decades thereafter, trickster tales, with their subtly and indirection, were necessary because blacks could not risk a direct attack on white society".[4]

Comic heartwarming tales

Comic and heartwarming African-American folktales “stimulate the imagination with wonders, and are told to remind us of the perils and the possibilities”.[5] The stories are about heroes, heroines, villains and fools. One story, The Red Feather, is a response to the intertwining of cultures, ending with heroes bringing forth gifts.[6] Rabbit Rides Wolf is a story that represents the amalgamation of African and Creek descent where a combined hero emerges during a time of conflict .[6]

Teaching life lessons

African folklore is a means to hand down traditions and duties through generations. Stories are often passed down orally at gatherings of groups of children. This type of gathering was known as Tales by Midnight and contained cultural lessons that prepared children for their future.[7] A Diversity of animals with human characteristics made the stories compelling to the young children and included singing and dancing or themes such as greediness, honesty, and loyalty.[7]

One story example used for generations of African children is the Tale of The Midnight Goat Thief that originated in Zimbabwe. The Midnight Goat Thief is a tale of misplaced trust and betrayal between two friends, a baboon and a hare, when a conflict between the two arises. The story teaches children to be loyal and honest.[7]

Ghosts and spirits

African-American tales of ghosts and spirits were commonly told of a spook or “haint” [8] or “haunt,” referring to repeated visits by ghosts or spirits that keep one awake at night.[9] The story Possessed of Two Spirits is a personal experience in conjuring magic powers in both the living and the spiritual world common in African-American folklore.[10] The story Married to a Boar Hog emerged during the colonial Revolution against the British.[6] The story is of a young woman who married a supernatural being figure, such as a boar, who saves her from a disease like leprosy, club foot, or yaws. Married to a Boar Hog is passed down from British Caribbean slaves in reference to their African Origin and the hardships they endured.[6]

Slavery

African-American tales of slavery often use rhetoric that can seem uncommon to the modern era as the language passed down through generations deviates from the standard for racial narrative. The Conjure Woman, a book of tales dealing with racial identity, was written by the African-American author, Charles W. Chesnutt, from the perspective of a freed slave.[11]

Chesnutt's tales represent the struggles freed slaves faced during the post-war era in the South. The author's tales provide a pensive perspective on the challenges of being left behind.

Chesnutt's language surrounding African American folklore derived from the standards of the racial narrative of his era. By using vernacular language, Chesnutt was able to deviate from the racial norms and formulate a new, more valorized message of folk heroes. Chesnutt writes "on the other side" of standard racial narratives, effectively refuting them by evoking a different kind of "racial project" in his fictional work.”[11]

African-American folktale examples

- A Story, A Story – by Gale E. Hayley[12]

- Afiong the Proud Princess[3]

- Anansi the Spider – by Gerald McDermott[12]

- Big Liz[13]

- Boo Hag[13]

- Br'er Bear's House[13]

- Br'er Rabbit

- Finding the Green Stone – by Alice Walker[12]

- Gullah storytelling

- Hold Him, Tabb[13]

- I Know Moon Rise[13]

- I'm Coming Down Now[13]

- John Henry the Steel Driving Man[13]

- Mirandy and Brother Wind[12]

- Mufaro's Beautiful Daughters – by John Steptoe[12]

- Never Mind Them Watermelons[13]

- No King as God[3]

- Signifying monkey

- Sukey and the Mermaid – by Robert D. San Souci[12]

- The Baby Mouse and the Baby Snake[3]

- The Black Cat's Message[13]

- The Calabash Kids – from Tanzania[3]

- The Cheetah and the Lazy Hunter – from the Zulu[3]

- The King's Daughters – from Nigeria[3]

- The Midnight Goat Thief[3]

- The Shrouded Horseman[13]

- The Talking Eggs – by Robert D. San Souci[12]

- The Tortoise and the Hare – from Nigeria[3]

- The Tortoise, the Dog and the Farmer – from Nigeria[3]

- The Value of a Person[3]

- Wait Until Emmet Comes[13]

- Why Dogs Chase Cats[13]

- Why Lizards Don't Sit[13]

- Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears – Verna Aardema[12]

- Why the Sky is Far Away – by Mary-Joan Gerson[12]

- Woe and Happiness[3]

See also

References

- Cunningham. African American Folktales. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Thomas A. Green (2009). African American Folktales. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-36295-8.

- "African Folktales « ANIKE FOUNDATION". anikefoundation.org. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- "The Trickster in African American Literature, Freedom's Story, TeacherServe®, National Humanities Center". nationalhumanitiescenter.org. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr.; Tatar, Maria (2017-11-14). The Annotated African American Folktales (First ed.). ISBN 9780871407535.

- African American folktales. Greenwood Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0313362958.

- "The Midnight Goat Thief « ANIKE FOUNDATION". anikefoundation.org. Retrieved 2018-11-12.

- Ford, Lynette. Affrilachian tales : folktales from the African-American Appalachian tradition (First ed.). Marion : Parkhurst Brothers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935166-67-2.

- Ford, Lynette (2012). Affrilachian tales : folktales from the African-American Appalachian tradition (First ed.). ISBN 978-1-935166-66-5.

- Affrilachian tales : folktales from the African-American Appalachian tradition (First ed.). 2012. ISBN 978-1-935166-66-5.

- Myers, Jeffrey (2003). "Other Nature: Resistance to Ecological Hegemony in Charles W. Chesnutt's "The Conjure Woman"". African American Review. 37 (1): 5–20. doi:10.2307/1512356. ISSN 1062-4783. JSTOR 1512356.

- "10 African and African American Folktales for Children". The New York Public Library. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

- "African-American folklore at Americanfolklore.net". americanfolklore.net. Retrieved 2018-11-05.

Further reading

- Coughlan, Margaret N., and Library of Congress. Children's Book Section. Folklore From Africa to the United States: an Annotated Bibliography. Washington: Library of Congress: for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off, 1976.

- Marsh, Vivian Costroma Osborne. Types And Distribution of Negro Folk-lore In America. [Berkeley], 1922.