African Civilization Society

The African Civilization Society was an emigration organization founded in 1858 by several prominent members of the historic African-American Weeksville community located in central Brooklyn, New York.[1]

Following the Civil War and emancipation of slaves, it changed its focus to helping provide basic needs to the millions of freedmen in the South, and to establishing schools to educate them. It recruited 129 teachers to go to the South to teach.

History

Founded in 1858, the organization was intended to promote emigration to Liberia, which gained independence in 1847, and create a competing "free-labor" cotton industry to the slavery-based cotton industries of the United States. In part the emphasis on emigration was prompted by great disappointment about the US Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision, which ruled that blacks had no standing as citizens in the country. This decision resulted in the disenfranchisement of many tax paying, landowning, and successful black and African American professionals and entrepreneurs.

While its philosophy was similar in some ways to the "Emigration to Africa" concept of such 19th-century groups as the American Colonization Society, the African Civilization Society was founded and led exclusively by blacks or African Americans.

Leadership

"The Society is composed of ministers and gentlemen of known and tried integrity..." including Henry Highland Garnet, Martin Delany, Junius C. Morel, Rev. R. H. Cain, Rev. A. A. Constantine, Robert Campbell, Theodore Cuyler (European American), George W. LeVere, James Myres, James Morris Williams, Peter Williams, Rev. Amos N. Freeman, Rufus L. Perry, John Sella Martin, Henry H. Wilson and many others. Abolitionist leader Fredrick Douglass strongly opposed such colonization, but he was otherwise close to several members of the society, with whom he had collaborated on efforts to gain rights for American blacks.

"Self-Reliance and Self-Government on the Principle of an African Nationality..." was featured as a founding value statement in the original constitution of the society. Following the Civil War and emancipation of slaves, the mission of the organization shifted to providing basic needs to freed people. The Society raised funds to establish schools and sent some 129 teachers to the South to take up educating the freedmen.

Publications

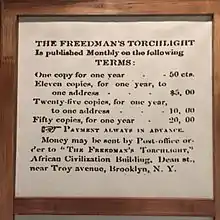

The institution was also known for printing two publications that circulated among communities of blacks and African Americans, a monthly called the Freedman's Torchlight and a weekly called the People's Journal.[2]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Freedman's Torchlight. |

- Wellman, Judith (2014-01-01). Brooklyn's promised land: the free black community of Weeksville, New York. ISBN 9780814725283.

- "THE AFRICAN CIVILIZATION SOCIETY.; Response to its Opponents No Connection with the Colonization Society". The New York Times. 1860-05-16. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-03-05.