Ain't I a Woman?

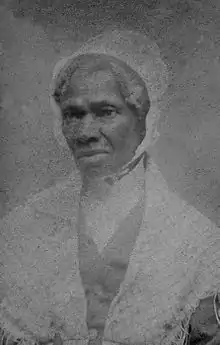

"Ain't I a Woman?" is a speech, delivered extemporaneously, by Sojourner Truth (1797–1883), born into slavery in New York State. Some time after gaining her freedom in 1827, she became a well known anti-slavery speaker. Her speech was delivered at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio, in 1851, and did not originally have a title.

The speech was briefly reported in two contemporary newspapers, and a transcript of the speech was published in the Anti-Slavery Bugle on June 21, 1851. It received wider publicity in 1863 during the American Civil War when Frances Dana Barker Gage published a different version, one which became known as Ain't I a Woman? because of its oft-repeated question. This later, better known and more widely available version has been the one referenced by most historians.

Background

.jpg.webp)

The phrase "Am I not a man and a brother?" had been used by British abolitionists since the late 18th century to decry the inhumanity of slavery.[1] This male motto was first turned female in the 1820s by British abolitionists,[2] then in 1830 the American abolitionist newspaper Genius of Universal Emancipation carried an image of a slave woman asking "Am I not a woman and a sister?"[1] This image was widely republished in the 1830s, and struck into a copper coin or token, but without the question mark, to give the question a positive answer.[2] In 1833, African American activist Maria W. Stewart used the words of this motto to argue for the rights of women of every race. Historian Jean Fagan Yellin argued in 1989 that this motto served as inspiration for Sojourner Truth, who was well aware of the great difference in the level of oppression of white versus black women. Truth was asserting both her gender and race by asking the crowd, "Am I not a woman?"[1][3]

Different versions

The first reports of the speech were published by the New York Tribune on June 6, 1851, and by The Liberator five days later. Both of these accounts were brief, lacking a full transcription.[4] The first complete transcription was published on June 21 in the Anti-Slavery Bugle by Marius Robinson, an abolitionist and newspaper editor who acted as the convention's recording secretary.[5] The question "Ain't I a Woman" does not appear in his account.[6]

Twelve years later, in May 1863, Frances Dana Barker Gage published a very different transcription. In it, she gave Truth many of the speech characteristics of Southern slaves, and she included new material that Robinson had not reported. Gage's version of the speech was republished in 1875, 1881, and 1889, and became the historic standard. This version is known as "Ain't I a Woman?" after its oft-repeated refrain.[7] Truth's style of speech was not like that of Southern slaves;[8] she was born and raised in New York, and spoke only Dutch until she was nine years old.[9][10][11]

Additions that Gage made to Truth's speech include the ideas that she could bear the lash as well as a man, that no one ever offered her the traditional gentlemanly deference due a woman, and that most of her 13 children were sold away from her into slavery. Truth is widely believed to have had five children, with one sold away, and was never known to claim more children.[6] Further inaccuracies in Gage's 1863 account conflict with her own contemporary report: Gage wrote in 1851 that Akron in general and the press in particular were largely friendly to the woman's rights convention, but in 1863 she wrote that the convention leaders were fearful of the "mobbish" opponents.[6] Other eyewitness reports of Truth's speech told a different story, one where all faces were "beaming with joyous gladness" at the session where Truth spoke; that not "one discordant note" interrupted the harmony of the proceedings.[6] In contrast to Gage's later version, Truth was warmly received by the convention-goers, the majority of whom were long-standing abolitionists, friendly to progressive ideas of race and civil rights.[6]

In 1972, Miriam Schneir published a version of Truth's speech in her anthology Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings.[12] This is a reprint of Gage's version without the heavy dialect or her interjected comments.[12][13] In her introduction to the work, she includes that the speech has survived because it was written by Gage.[12]

The speech

1851 version by Robinson

Marius Robinson, who attended the convention and worked with Truth, printed the speech as he transcribed it in the June 21, 1851, issue of the Anti-Slavery Bugle.[14]

One of the most unique and interesting speeches of the convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave. It is impossible to transfer it to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones. She came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity: "May I say a few words?" Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded:[15]

I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman's rights. [sic] I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal. I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if a woman have a pint, and a man a quart – why can't she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, – for we can't take more than our pint'll hold. The poor men seems to be all in confusion, and don't know what to do. Why children, if you have woman's rights, give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they won't be so much trouble. I can't read, but I can hear. I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well, if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.[15]

1863 version by Gage

The speech was recalled 12 years after the fact by Gage, an activist in the woman's rights and abolition movements. Gage, who presided at the meeting, described the event:[16]

The leaders of the movement trembled on seeing a tall, gaunt black woman in a gray dress and white turban, surmounted with an uncouth sunbonnet, march deliberately into the church, walk with the air of a queen up the aisle, and take her seat upon the pulpit steps. A buzz of disapprobation was heard all over the house, and there fell on the listening ear, 'An abolition affair!" "Woman's rights and niggers!" "I told you so!" "Go it, darkey!" . . Again and again, timorous and trembling ones came to me and said, with earnestness, "Don't let her speak, Mrs. Gage, it will ruin us. Every newspaper in the land will have our cause mixed up with abolition and niggers, and we shall be utterly denounced." My only answer was, "We shall see when the time comes."

The second day the work waxed warm. Methodist, Baptist, Episcopal, Presbyterian, and Universalist minister came in to hear and discuss the resolutions presented. One claimed superior rights and privileges for man, on the ground of "superior intellect"; another, because of the "manhood of Christ; if God had desired the equality of woman, He would have given some token of His will through the birth, life, and death of the Saviour." Another gave us a theological view of the "sin of our first mother."

There were very few women in those days who dared to "speak in meeting"; and the august teachers of the people were seemingly getting the better of us, while the boys in the galleries, and the sneerers among the pews, were hugely enjoying the discomfiture as they supposed, of the "strong-minded." Some of the tender-skinned friends were on the point of losing dignity, and the atmosphere betokened a storm. When, slowly from her seat in the corner rose Sojourner Truth, who, till now, had scarcely lifted her head. "Don't let her speak!" gasped half a dozen in my ear. She moved slowly and solemnly to the front, laid her old bonnet at her feet, and turned her great speaking eyes to me. There was a hissing sound of disapprobation above and below. I rose and announced, "Sojourner Truth," and begged the audience to keep silence for a few moments.

The tumult subsided at once, and every eye was fixed on this almost Amazon form, which stood nearly six feet high, head erect, and eyes piercing the upper air like one in a dream. At her first word there was a profound hush. She spoke in deep tones, which, though not loud, reached every ear in the house, and away through the throng at the doors and windows.

The following is the speech as Gage recalled it in History of Woman Suffrage which was, according to her, in the original dialect as it was presented by Sojourner Truth:

"Wall, chilern, whar dar is so much racket dar must be somethin' out o' kilter. I tink dat 'twixt de niggers of de Souf and de womin at de Norf, all talkin' 'bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what's all dis here talkin' 'bout?

"Dat man ober dar say dat womin needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted ober ditches, and to hab de best place everywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gibs me any best place!" And raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunder, she asked. "And a'n't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! (and she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing her tremendous muscular power). I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And a'n't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear de lash as well! And a'n't, I a woman? I have borne thirteen chilern, and seen 'em mos' all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And a'n't I a woman?

"Den dey talks 'bout dis ting in de head; what dis dey call it?" ("Intellect," whispered some one near.) "Dat's it, honey. What's dat got to do wid womin's rights or nigger's rights? If my cup won't hold but a pint, and yourn holds a quart, wouldn't ye be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full?" And she pointed her significant finger, and sent a keen glance at the minister who had made the argument. The cheering was long and loud.

"Den dat little man in black dar, he say women can't have as much rights as men, 'cause Christ wan't a woman! Whar did your Christ come from?" Rolling thunder couldn't have stilled that crowd, as did those deep, wonderful tones, as she stood there with outstretched arms and eyes of fire. Raising her voice still louder, she repeated, "Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothin' to do wid Him." Oh, what a rebuke that was to that little man.

Turning again to another objector, she took up the defense of Mother Eve. I can not follow her through it all. It was pointed, and witty, and solemn; eliciting at almost every sentence deafening applause; and she ended by asserting: "If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women togedder (and she glanced her eye over the platform) ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now dey is asking to do it, de men better let 'em." Long-continued cheering greeted this. "'Bleeged to ye for hearin' on me, and now ole Sojourner han't got nothin' more to say."[17]

Gage described the result:

Amid roars of applause, she returned to her corner, leaving more than one of us with streaming eyes, and hearts beating with gratitude. She had taken us up in her strong arms and carried us safely over the slough of difficulty turning the whole tide in our favor. I have never in my life seen anything like the magical influence that subdued the mobbish spirit of the day, and turned the sneers and jeers of an excited crowd into notes of respect and admiration. Hundreds rushed up to shake hands with her, and congratulate the glorious old mother, and bid her God-speed on her mission of 'testifyin' agin concerning the wickedness of this 'ere people.'[17]

Legacy

There is no single, undisputed official version of Truth's speech. Robinson and Truth were friends who had worked together concerning both abolition of slavery and women's rights, and his report is strictly his recollection with no added commentary. Since Robinson's version was published in the Anti-Slavery Bugle, the audience is largely concerned with the rights of African Americans rather than women; it is possible Robinson's version is framed for his audience. Although Truth collaborated with Robinson on the transcription of her speech, Truth did not dictate his writing word for word.[18]

The historically accepted standard version of the speech was written by Gage, but there are no reports of Gage working with Truth on the transcription.[18] Gage portrays Truth as using a Southern dialect, which the earliest reports of the speech do not mention. Truth is said to have prided herself on her spoken English, and she was born and raised in New York state, speaking only Jersey Dutch until the age of 9.[19] The dialect in Gage's 1863 version is less severe than in her later version of the speech that she published in 1881. The rearticulation in the different published versions of Gage's writings serve as the metonymic transfiguration of Truth.[20] In addition, the crowd Truth addressed that day consisted of mainly white, privileged women. In Gage's recollection, she describes that the crowd did not want Truth to speak because they did not want people to confuse the cause of suffrage with abolition, despite many reports that Truth was welcomed with respect. Although Gage's version provides further context, it is written as a narrative: she adds her own commentary, creating an entire scene of the event, including the audience reactions. Because Gage's version is built primarily on her interpretation and the way she chose to portray it, it cannot be considered a pure representation of the event.[18]

Contemporary relevance

Sojourner Truth's Ain't I a Woman is a critique of single axis analysis of domination, and how an analysis that ignores interlocking identities prevents liberation. Scholars Avtar Brah and Ann Phoenix discuss how Truth's speech can be read as an intersectional critique of homogenous activist organizations. Truth's speech at the convention "deconstructs every single major truth-claim about gender in a patriarchal slave social formation",[21] as it asks the audience to see how their expectations of gender have been played out within her lived experience. Brah and Phoenix write,

"Sojourner Truth's identity claims are thus relational, constructed in relation to white women and all men and clearly demonstrate that what we call 'identities' are not objects but processes constituted in and through power relations."[21]

References

- Stetson, Erlene; David, Linda (31 August 1994). Glorying in Tribulation: The Life Work of Sojourner Truth. MSU Press. p. 1840. ISBN 9780870139086.

- Midgley, Clare (2007). "British Abolition and Feminism in Transatlantic Perspective". In Kathryn Kish Sklar, James Brewer Stewart (ed.). Women's Rights and Transatlantic Antislavery in the Era of Emancipation. Yale University Press. p. 134. ISBN 9780300137866.

- Ducille, Ann (6 July 2006). "On canons: anxious history and the rise of black feminist literary studies". In Ellen Rooney (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Feminist Literary Theory. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9781139826631.

- Fitch, Suzanne Pullon; Mandziuk, Roseann M. (1997). Sojourner Truth as orator: wit, story, and song. Great American Orators. 25. Greenwood. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-313-30068-4.

- Brezina, Corona (2004). Sojourner Truth's "Ain't I a woman?" speech: a primary source investigation. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-4042-0154-5.

- Mabee, Carleton; Susan Mabee Newhouse. Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend, NYU Press, 1995, pp. 67–82. ISBN 0-8147-5525-9

- Craig, Maxine Leeds. Ain't I A Beauty Queen: Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race, Oxford University Press USA, 2002, p. 7. ISBN 0-19-515262-X

- Brezina, Corona (2005). Sojourner Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?" Speech: A Primary Source Investigation. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 29. ISBN 9781404201545.

- "Sojourner Truth Page". American Suffragist Movement. Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- "Sojourner Truth Page". Fordham University. Archived from the original on 13 January 2007. Retrieved 30 December 2006.

- The Narrative of Sojourner Truth by Olive Gilbert and Sojourner Truth. Project Gutenberg. March 1999. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- Schneir, Miriam (1972). Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings. Vintage Books.

- "Compare the Speeches". The Sojourner Truth Project. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- "Amazing Life page". Sojourner Truth Institute site. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- Marable, Manning (2003). Let Nobody Turn Us Around: Voices of Resistance, Reform, and Renewal: an African American Anthology. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9780847683468.

- History of Woman Suffrage, 2nd ed. Vol.1, Rochester, NY: Charles Mann, 1889, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage

- History of Woman Suffrage. 1. Rochester, Anthony. 1887–1902. p. 116.

- Siebler, Kay (Fall 2010). "Teaching the Politics of Sojourner Truth's "Ain't I a Woman?"" (PDF). Pedagogy. 10 (3): 511–533. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Murphy, Larry (2001), Sojourner Truth: A Biography, Greenwood, p. xiv, ISBN 978-0-313-35728-2

- Mandziuk, Roseann M.; Suzanne Pullon Fitch (2001). "The rhetorical construction of Sojourner truth". Southern Communication Journal. 66 (2): 120–138. doi:10.1080/10417940109373192.

- Brah, Avtar; Phoenix, Ann (2004). "Ain't I A Woman? Revisiting Intersectionality". Journal of International Women's Studies: 77.

Further reading

- hooks, bell (Fall 1991). "Theory as liberatory practice". Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 4 (1): 1–12. Pdf.

- MacKinnon, Catharine A. (Fall 1991). "From practice to theory, or what is a white woman anyway?". Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 4 (1): 13–22. Pdf.

- Romany, Celina (Fall 1991). "Ain't I a feminist?". Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 4 (1): 23–33. Pdf.

- Rhode, Deborah L. (Fall 1991). "Enough said". Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 4 (1): 35–38. Pdf.

External links

- Version of Gage, 1878 in google books, without pagination, Ch. 7, from Man Cannot Speak for Her. Volume 2: Key Texts of the Early Feminists. ISBN 0275932672

- The Sojourner Truth Project, a website that compares the text of each version of the speech and provides audio reading of both.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |