Andrea Sacchi

Andrea Sacchi (30 November 1599 – 21 June 1661) was an Italian painter of High Baroque Classicism, active in Rome. A generation of artists who shared his style of art include the painters Nicolas Poussin and Giovanni Battista Passeri, the sculptors Alessandro Algardi and François Duquesnoy, and the contemporary biographer Giovanni Bellori.

Andrea Sacchi | |

|---|---|

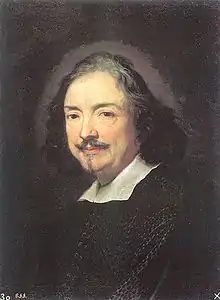

Portrait by Maratta. | |

| Born | 30 November 1599 |

| Died | 21 June 1661 (aged 61) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Baroque |

| Patron(s) | Francesco Maria del Monte[1] |

Early training

Sacchi was born in Rome.[2] His father, Benedetto, was an undistinguished painter. According to the biographer Giovanni Pietro Bellori (who was also a great friend of Sacchi's), Andrea initially entered the studio of Cavalier d'Arpino. These are Bellori's words:

[...]hence Benedetto, his father, as soon as he saw that he was being outstripped by his son in his childhood, no longer having the courage to educate him, wisely thought to provide him with a better master and recommended him to Cavalier Giuseppe d’Arpino, who gladly took him into his school, perceiving him to be more attentive and bent on progress than any other youth.[3]

Sacchi later entered Francesco Albani's workshop and spent most of his time in Rome where he eventually died. Much of his early career was helped by the regular patronage by Cardinal Antonio Barberini, who commissioned art for the Capuchin church in Rome and the Palazzo Barberini.

Mature style

A contemporary rival of Pietro da Cortona, Sacchi studied the paintings of Raphael and the influence of Raphael is apparent in a number of his works, particularly with reference to the use of few figures and their expressions.[4] He reputedly travelled to Venice and Parma and studied the works of Correggio.

Two of his major works on canvas are altarpieces now displayed in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, the painting gallery in the Vatican (see Main works below).

Controversy with Pietro da Cortona

As a young man, Sacchi had worked under Cortona at the Villa Sacchetti at Castelfusano (1627–1629). But in a set of public debates at the Accademia di San Luca, the guild for artists in Rome, he strongly criticized Cortona's exuberance. The debate is significant because it indicates how two of the leading proponents of the prevailing styles in painting, now called 'Classical' and 'Baroque', discussed the differences between their work.

In particular, Sacchi advocated that since a unique, individual expression, gesture and movement needed to be assigned to each figure in a composition, so a painting should only have a few figures.[5] In a crowded composition, the figures would be deprived of individuality, and thus cloud the particular meaning of the piece. In some ways this was a reaction against the zealous excess of crowds in paintings by artists such as Zuccari in the previous generation, and by Cortona among his contemporaries. Simplicity and unity were essential to Sacchi who, drawing an analogy to poetry, likened painting to tragedy. In his counter-argument, Cortona made the case that large paintings with many figures were like an epic which could develop multiple sub-themes. But for Sacchi, the encrustation of a painting with excess decorative details, including melees of crowds, would represent something akin to 'wall-paper' art rather than focused narrative. Among the partisans of Sacchi's argument for simplicity and focus were his friends, the sculptor Algardi and painter Poussin. The controversy was however less pitched and monolithic than some might suggest. In fact, Poussin's biographer Bellori recounts that the artist 'used to laugh at those who contract for a [history painting] with six or eight figures or some other fixed number.'[6]

Sacchi and Albani, among others, shared dissatisfaction with the artistic depiction of low or genre subjects and themes, such as those preferred by the Bamboccianti and even the Caravaggisti. They felt that high art should focus on exalted themes- biblical, mythological, or from classical ancient history.

Sacchi, who worked almost always in Rome, left few pictures visible in private galleries. He had a flourishing school: Carlo Maratta was a younger collaborator or pupil. In Maratta's large studio, Sacchi's preference for a grand manner style would find pre-eminence among Roman circles for decades to follow. But many others worked under him or his influence including Francesco Fiorelli, Luigi Garzi, Francesco Lauri, Andrea Camassei, and Giacinto Gimignani. Sacchi's own illegitimate son Giuseppe, died young after high hopes for his future.[7]

Sacchi died at Nettuno in 1661.

Main works

Allegory of Divine Wisdom at the Palazzo Barberini

This fresco by Sacchi in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome is considered his masterpiece. It depicts Divine Wisdom (1629–33),.[8] The work was inspired by Raphael's Parnasus in the Raphael's Rooms in the Vatican Palace.[9]

According to the American art historian Joseph Connors:

Urban VIII's personal emblem is the rising sun [and a] visitor to the palace would have seen the sun of Divine Wisdom and the constellation of the lion (as well as in the throne) in Sacchi's fresco... the eye [can] take in the fresco but also to penetrate beyond to the chapel next door. From the right point of view the sun of Divine Wisdom looks as though it is hovering over the dome of the chapel, "radiating downward its beneficent light". ... Scott's astrological interpretation of ... is convincing because it is also a political interpretation. Because of the favorable conjunction of the stars at two key moments, Urban VIII's birth and election, the Barberini were "born and elected to rule." Campanella could have told the pope that when he was elected the sun had entered into the Great Conjunction with Jupiter (whose eagle is shown by Sacchi in conjunction with the sun and the lion). Urban VIII's nephew Taddeo Barberini, the patron of this wing of the palace and the relative on whom the family pinned its hopes for offspring and immortality, had a natal chart similar to his uncle's, and by coincidence so did the child born to him during his residence in the palace. The little chapel adjacent to Sacchi's fresco was designed for the baptism of such children, and its frescoes carried all the usual talismans of fertility. The stars could be expected to look favorably on a family "born and elected to rule" down the generations.[10]

St Gregory and the Miracle of the Corporal

Also known as the Miracle of St Gregory the Great, this painting was executed in 1625-57. It is now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana.

The canvas portrays the legend that the Empress Constantia had begged Pope Gregory I to give her relics of the body of Saints Peter and Paul, but the pope, not daring to disturb the remains of these saints, sent her a fragment of the linen which had enveloped the remains of Saint John the Evangelist. Constantia rejected this gift from the pope as insufficient. Then Gregory, to prove the power of relics to work miracles (and justify their worth), placed the cloth on the altar, and, after praying, pierced it with a knife, and blood flowed from it as from a living body. In 1771, a mosaic copy of this painting was made for the Basilica of St Peter's.[11] This painting echoes positions stated in the canons of the Council of Trent: wherein relics had an important role in miracles, the pope served as the final interpreter of sanctity, and finally it was a metaphor of the validity of the eucharist as the true body of Christ.

Vision of St. Romuald

Completed in 1631, this painting in the Pinacoteca Vaticana recalls an episode in the life of the early Benedictine monk, Saint Romuald, of the Camaldolese Order, who is said to have dreamt that members of his Order wearing white ascended into heaven (as seen in background). The serenity and gravity of the monks, arrayed as in philosophic discourse, is characteristic of Sacchi.

Other works

Other leading examples of Sacchi's work are The Death of St. Anne, in San Carlo ai Catinari, Rome;St. Andrew, in the Quirinal Palace; St. Joseph, at Caponile Case; and The Three Marys (1634), at Palazzo Barberini, Rome. Other altarpieces by Sacchi are in Perugia, Foligno and Camerino.

References

- Camiz, Franca Trinchieri (1991). "Music and Painting in Cardinal del Monte's Household". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 26: 213–226. doi:10.2307/1512913. JSTOR 1512913. S2CID 191619204.

- For a long time, Sacchi scholarship believed the painter was born in Nettuno, but this information is now regarded as incorrect following many academic studies such as those by Ann Sutherland Harris. As far as Andrea Sacchi's birth in Rome and not in Nettuno is concerned, see Ann Sutherland Harris, "Andrea Sacchi", L'idea del bello: viaggio per Roma nel Seicento con Giovan Pietro Bellori, exh. cat. edited by E. Borea and C. Gasparri, Rome (Palazzo delle Esposizioni), Roma: De Luca, 2000, vol. II, 2 vols., p.442-444. Sacchi's death in Rome is proven by his will, now at the State Archives in Rome. The will has been transcribed and may be found in Antonio D'avossa, Andrea Sacchi, Roma: Kappa, 1985.

- See Giovanni Pietro Bellori, The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects, translated by Alice Sedgwick Wohl, edited by H. Wohl, introduction by T. Montanari, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010, p.375.

- Wittower, 1980, 621-3

- Wittkower, 1980, p.263

- Gian Pietro Bellori, "Life of Nicolas Poussin" in The Lives of the Modern Painters, sculptors and Architects (Cambridge University Press: 2010), p. 323.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sacchi, Andrea". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 970.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sacchi, Andrea". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 970. - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2005-02-14. Retrieved 2006-03-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Wittkower, 1980, p. 263

- Joseph Connors, New York Review of Books Archived February 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Sutherland Harris, Ann (1977). Andrea Sacchi : complete edition of the paintings with a critical catalogue. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Rudolf Wittkower, Rudolf (1993). Pelican History of Art (ed.). Art and Architecture Italy, 1600-1750. 1980. Penguin Books. pp. 261–266.

- Marcheteau de Quinçay, Christophe (2007). Didon abandonnée de Andrea Sacchi. Caen: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen.