Andreas Reyher

Andreas Reyher (4 May 1601Julian - 12 April 1673Gregorian) was a German teacher, education reformer and lexicographer.[1][2]

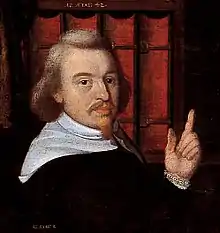

Andreas Reyher | |

|---|---|

Andreas Reyher cropped/extracted from a family group by August Erich, 1643 | |

| Born | 4 May 1601Julian |

| Died | 12 April 1673Gregorian |

| Occupation | Teacher Schools administrator and education reformer |

| Spouse(s) | 1. Katharina Abesser (1612–1657) 2. Anna Blandine Bachoff (1636–1670) |

| Children | first marriage

second marriage

|

| Parent(s) | Michael Reyher (1557-1634) Ottilie Albrecht (?-1619) |

Life

Provenance and early years

Andreas Reyher was born at exactly midday in Heinrichs. Heinrichs was a village which, while Reyher was a growing up, became engulfed in a series of witch trials which would lead to ten village women being killed by burning and one by being beheaded after which her body was burnt anyway.[3] (The victims were rehabilitated in 2011.)[3] It was located just to the west of Suhl, in the hills between Frankfurt and Leipzig. Michael Reyher (1557-1634), his father, was a successful wine merchant. His mother, born Ottilie Albrecht, was the daughter of the local Schultheiß (chief municipal administrator). She died in 1619 after being seriously ill for the last eleven years of her life.[1] He attended school in Suhl from 1614, rapidly mastering everything he was taught about Latin and Maths. His father was gratified that his clever son would be able to follow him into the wine trade, but by the end of 1616 his father's aspirations for the boy had changed. Foreseeing the possibility of an academic career, at the start of 1617 his father switched him to a Gymnasium (a secondary school with enhanced academic possibilities) in nearby Schleusingen. Andreas again mastered the most demanding curriculum that the school could provide and on 16 August 1621, although he did not come from a particularly academic family, Andreas Reyher received authorisation to move on to study at a university.[2]

Student years

At the end of 1621 he moved to Leipzig where he lodged with the well connected merchant Georg Winckler in order to study Philosophy and Theology at the university. He was impeded in his studies by shortage of cash as a result of which he had to support himself with extensive tutoring work, although that provided experience which would also prove of value in his subsequent career.[2] In 1624 he began attending lectures by the theologian Heinrich Höpfner.[4] He received a BA degree ("Baccalaureus Artium & Philosophiae") in September 1625 and in January 1627 an MA degree, later that year submitting his work to a disputation and becoming a Master of Philosophy ("Philosophiae Magister").[1] After that he began to give lectures. In 1631 he was admitted to the Leipzig University Philosophy faculty as a university lecturer. His first publications also date from this period.[4]

School rector and education reformer

On 19 April 1632 he was offered the headship at the Hennebergisches Gymnasium (secondary school) at Schleusingen.[1] He accepted the appointment, taking up the position on 10 December of that same year[2] and remaining in the post for seven years. In 1639 he received and accepted an unsolicited invitation to take up an appointment as rector at the St. John's School in Lüneburg.[1] Less than years later he was appointed rector at the Illustrious Gymnasium at Gotha, where he was installed on 11 January 1641. The appointment offered a rich range of opportunities. Gotha was home to the royal court of Saxe-Weimar. Duke Ernest had been taking a close personal interest in the duchy's school system, which had fallen into sad decline in the context of the destruction, depopulation, plague and economic decline that accompanied the Thirty Years' War. Teachers remained in place only because they had no where else to go. Educational strategy was largely restricted to rote learning. Discipline was imposed with brutish barbarity.[2] As the leaders and negotiators of the belligerent states stumbled uncertainly towards peace, in Saxe-Weimar Reyher's position as rector of the Ernestinum Gymnasium effectively made him the duke's senior policy advisor on education, regarding both junior and senior schools.[2] Andreas Reyher remained in post at the Ernestium (and as de facto royal education advisor) for the rest of his life.[4]

Reyher's mission in Gotha became the reorganisation of the schools system in the duchy, applying the principals enunciated by education experts of the time including, notably, Wolfgang Ratke.[2] In 1645 he introduced streaming according to ability at his Gymnasium in Gotha.[4]

In 1644 the duke also set him in charge of the "Peter Schmid Book Printing Works" which later became the "Engelhard-Reyhersche Book Printing Works", at one stage under the direction of his son Christoph Reyher (1642–1724).[1]

Works

The school laws and methods developed during Reyher's time provided an important basis for a standardised education structure in junior schools. He saw to it that, for the first time in any German state, universal school attendance became legally compulsory. He insisted that natural sciences and citizenship be included in the curriculum.[2]

Another major contribution to advancing the schools system was his development of standardised curricula and his production of text books, many of which were published and distributed far beyond the frontiers of Saxe-Gotha.[2]

Until the eighteenth century the schools system in Saxe-Gotha was the only one of its kind in Germany, and as the appetite for improved educational structures increased it became a template for other German states. There were those who said that the Duke of Saxe-Gotha's peasants were better educated than the nobility in other jurisdictions.[5]

The name of Andreas Reyher is also associated with the establishment of the first printing business in Gotha, and one of the oldest printing businesses in the whole Thuringia region.[6] He was the publisher of numerous text books and other scholarly volumes, but also the publisher and printer of books written by himself.

Family

On 6 May 1633 Andreas Reyher married Katharina Abesser (1612–1657), the daughter of Sebastian Abesser the Superintendent (ecclesiastical administrator) in Suhl. The marriage resulted in twelve recorded children of whom seven reached adulthood.[2]

Following the death of his first wife, on 18 January 1659 Andreas Reyher married Anna Blandine Bachoff (1636–1670). Her father, Friedrich Bachoff, worked in Gotha's public administration (als "Ministraturkollektor"). This marriage resulted in a further three recorded sons and three recorded daughters. However, four of these, including all three daughters, predeceased their father.[2]

Celebration

In 1904 Gotha's prestigious new Reyherschule ("Reyher School") opened, named in honour of Andreas Reyher. Reyherstrasse ("Reyher Street"), which runs along the north side of the school grounds, was named after him at the same time.

References

- Andreas Reyher (1675). "Andreas Reyher (1601–1673): Lebenslauf". Christoph Reyhern (printer), Gotha & Forschungsstelle für Personalschriften an der Philipps-Universität Marburg (by whom republished online approximately 340 years later). Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Max Berbig (1907). "Reyher: Andreas R., hervorragender Pädagog des 17. Jahrhunderts, geboren in dem Dorfe Heinrichs bei Suhl am 4. Mai 1601 ..." Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 322–325. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Hartmut Hegeler (compiler-publisher). "Heinrichs, Amt Suhl sächsisch ... Heinrichs war zwischen 1608 und 1665 von Hexenverfolgungen betroffen" (PDF). Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Andreas Reyher (1601–1673): Zeitleiste". Forschungsstelle für Personalschriften an der Philipps-Universität Marburg. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Stephan Sehlke (2011). Das geistige Boizenburg: Bildung und Gebildete im und aus dem Raum Boizenburg vom 13. Jahrhundert bis 1945. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 126. ISBN 978-3-8448-0423-2.

- Herbert Jaumann (2004). Handbuch Gelehrtenkultur der Frühen Neuzeit. Walter de Gruyter. p. 552. ISBN 978-3-11-016069-7.