Antirhodos

Antirhodos (sometimes Antirrhodos or Anti Rhodes) was an island in the eastern harbor of Alexandria, Egypt, on which a Ptolemaic palace was sited. The island was occupied until the reigns of Septimius Severus and Caracalla[1] and it probably sank in the 4th century, when it succumbed to earthquakes and a tsunami following an earthquake in the eastern Mediterranean near Crete in the year 365. The site now lies underwater, near the seafront of modern Alexandria, at a depth of approximately five metres (16 ft).[2]

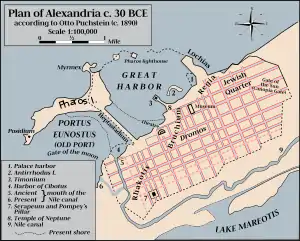

Map of ancient Alexandria. "2" marks the island of Antirhodos. | |

Map of Egypt showing the location of Antirhodos. | |

| Location | Alexandria |

|---|---|

| Region | Egypt |

| Coordinates | 31°12′24″N 29°54′01″E |

| Altitude | −5 m (−16 ft) |

| Type | Island |

| Part of | Alexandria Port |

| Length | 300 metres (980 ft) |

| Area | 500 ha (1,200 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 250BC |

| Cultures | Ptolemaic Kingdom |

| Associated with | Cleopatra |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1996 |

| Archaeologists | Franck Goddio |

| Condition | Submerged |

Descriptions of the island were recorded in classical antiquity by Greek geographers and historians. Strabo described a royal house on Antirhodos in 27 BC[3] and wrote that the island's name ("counter-Rhodes") derived from the island's rivalry with the island of Rhodes.[4] Antirhodos was part of Alexandria's ancient royal port called the Portus Magnus, which also included parts of the Lochias peninsula in the East and the island of Pharos in the West.[5] The Portus Magnus was abandoned and left as an open bay after an earthquake in the 8th century.

Rediscovery

In 1996, underwater archaeology in the harbour of Alexandria conducted by Franck Goddio located the island and found that it was on the opposite side of the harbour from where it was placed by Strabo.[6] The excavations showed that the island had been occupied from before the founding of Alexandria and that it was totally levelled and prepared for construction around 250BC.[3]

The island was small (about 500 hectares or 1,200 acres) and fully paved,[7] with three branches leading in different directions. The main branch was 300 metres (1,000 ft) long and had an esplanade facing the site of the Caesarium temple on the mainland seafront.

On the esplanade Goddio uncovered the remains of a relatively modest (90 metres by 30 metres) marble-floored 3rd century BC palace, believed to have been Cleopatra's royal quarters. On another narrow branch of the island there was a small Temple of Isis which had at its entrance a life-size granite statue representing a shaven-headed Egyptian priest of the goddess Isis carrying a jar topped with an image of Osiris.[8] A pair of granite sphinxes flanked the statue, one of which had the head of Cleopatra's father.

Between the branches on the eastern side of the island there was a small port with docks.[1] Here there was a series of 60 columns, each 1 metre in diameter and 7 metres in length, made of red Egyptian granite and topped with a decorated crown. Ancient paintings indicate that the columns acted as the ceremonial gateway to the island.[9] The wreck of a 30-metre long 1st century BC or 1st century AD Roman ship has been identified in the vicinity of the port.[10] Evidence from a hole in the ship's hull suggests that it could have sunk after being rammed by another boat.[2]

The site of Mark Antony's uncompleted palace, the Timonium, has also been located on the island. Other finds include a colossal stone head thought to be of Cleopatra's son Caesarion, and a huge quartzite block with an engraving of a pharaoh and an inscription indicating that it depicts Seti I, father of Ramses II. Some of the pharaonic objects on the site had been brought from Heliopolis by the Ptolemaic rulers and re-used to construct their buildings. The remains on the island do not seem to date from later than the Ptolemaic period, suggesting the palace may have been abandoned soon after Cleopatra's death and the absorption of Egypt into the Roman Empire.[3]

References

Citations

- "Expositions (Grand Palais, Paris, 2006-2007): Trésors engloutis d'Égypte" [Exhibition (Grand Palais, Paris, 2006-7): Egypt's Sunken Treasures]. www.bubastis.be (in French). 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- "Sphinx of Cleopatra's father emerges from waves". CNN News. 29 October 1998. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Vizard, Frank (May 1999). "In Search of Cleopatra's Palace". Popular Science. 254 (5). Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- Strabo. "The Geography of Strabo: Book XVII". The University of Chicago. Bill Thayer. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

They so called it as being a rival of Rhodes

- Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: Walton and Maberly. p. 27. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Michael Sedge. "Cleopatra's Sunken Palace". Virtual Egypt. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Mirsky, Steve (31 January 2010). "Cleopatra's Alexandria Treasures". Scientific American. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- "Stadtplan des antiken Alexandria" [City Map of ancient Alexandria]. ORF. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

Finds such as the 1.70-meter-high statue of a high priest indicate that the island once held once a small shrine dedicated to the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis.

- Atif, Wessam. "Diving into Egyptian History: The Rediscovery of Cleopatra's Sunken Palace and Diving it Today". Underwater Photography Guide. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- Sandrin, Patrice; Belov, Alexander; Fabre, David (March 2013). "The Roman Shipwreck of Antirhodos Island in the Portus Magnus of Alexandria, Egypt". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 42 (1): 44–59. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2012.00363.x.

Bibliography

- Puchstein, Otto (1894). "Antirrodos". Paulys Realencyclopädie der klassischen Altertumswissenschaft [Pauly's Real Encyclopedia of Classical Antiquity] (in German). 1&2. Stuttgart.

- "Herrscher der bewohnten Erde" [Ruler of the Inhabited Earth]. Der Spiegel (44). 27 October 1997. Retrieved 23 July 2015.