Aramaic of Hatra

Aramaic of Hatra or Hatran Aramaic designates an ancient Aramaic dialect, that was used in the region of Hatra, in northeastern parts of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), approximately from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century CE.[1][2]

| Hatran | |

|---|---|

| Hatrean | |

| Region | Hatra |

| Era | 100 BCE – 240 CE |

| Hatran alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

qly | |

| Glottolog | hatr1234 |

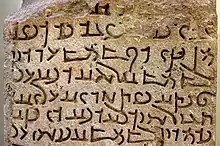

It is attested by inscriptions from various local sites, that were published by W. Andrae in 1912 and were studied by S. Ronzevalle and P. Jensen. The excavations undertaken by the Iraqi Department of Antiquities brought to light more than 100 new texts, the publication of which was undertaken by F. Safar in the journal Sumer. The first four series were the subject of reviews in the journal Syria. The texts range in date from the 2nd or 3rd century BCE to the destruction of the city c. 240 CE; the earliest dated text provides a date of 98 BCE.

For the most part, these inscriptions are short commemorative graffiti with minimal text. The longest of the engraved inscriptions does not have more than 13 lines. It is therefore difficult to identify more than a few features of the Aramaic dialect of Hatra, which shows overall the greatest affinity to Syriac.

The stone inscriptions bear witness to an effort to establish a monumental script. This script is little different from that of the Aramaic inscriptions of Assur (possessing the same triangular š, and the use of the same means to avoid confusion between m, s, and q). The ds and the rs are not distinguished from one another, and it is sometimes difficult not to confuse w and y.

Grammatical Sketch

Orthography

The dialect of Hatra is no more consistent than that of Palmyra in its use of matres lectiones to indicate the long vowels ō and ī; the pronominal suffix of the 3rd person plural is written indiscriminately, and in the same inscription one finds hwn and hn, the quantifier kwl and kl "all", the relative pronoun dy and d, and the word byš and bš "evil".

Phonology

The following features are attested:

Lenition

A weakening of ‘ayn; in one inscription, the masculine singular demonstrative adjective is written ‘dyn (‘dyn ktb’ "this inscription") which corresponds to Mandaic and Jewish Babylonian Aramaic hādēn. Similar demonstratives, ‘adī and ‘adā, are attested in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.

Dissimilation

- The surname ’kṣr’ "the court" (qṣr) and the proper name kṣy’, which resembles Nabataean qṣyw and the Safaitic qṣyt, demonstrate a regressive dissimilation of emphasis, examples of which are found already in Old Aramaic, rather than a loss of the emphasis of q, which is found in Mandaic and Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.

- Dissimilation of geminate consonants through n-insertion: the adjective šappīr "beautiful" is regularly written šnpyr; likewise, the divine name gadd "Tyché" is once written gd, but more commonly appears as gnd. This is a common phenomenon in Aramaic; Carl Brockelmann, however, claims that it is a characteristic feature of the northern dialect to which Armenian owes its Aramaic loans.

Vocalism

The divine name Nergal, written nrgl, appears in three inscriptions. The pronunciation nergōl is also attested in the Babylonian Talmud (Sanhedrin, 63b) where it rhymes with tarnəgōl, "cock."

Syntactic Phonology

The Hatran b-yld corresponds to the Syriac bēt yaldā "anniversary". The apocope of the final consonant of the substantive bt in the construct state is not attested in either Old Aramaic or Syriac; it is, however, attested in other dialects such as Jewish Babylonian Aramaic and Jewish Palestinian Aramaic.

Verbal Morphology

- The Perfect: The first person singular of the perfect appears only in one inscription: ’n’ ... ktbyt "I ... wrote"; this is the regular vocalization elsewhere among those Aramaic dialects in which it is attested.

- The causative perfect of qm "demand" should be vocalized ’ēqīm, which is evident from the written forms ’yqym (which appears beside ’qym), the feminine ’yqymt, and the third person plural, ’yqmw. This detail distinguishes Hatran as well as Syriac and Mandaic from the western Jewish and Christian dialects. The vocalization of the preformative poses the same problem as the Hebrew hēqīm.

- The Imperfect: The third person of the masculine singular is well attested; it consistently has the preformative l-.

- In the jussive: lṭb bꜥšym "that Bacl Šemēn may announce it" (Syriac ’aṭeb(b)), l’ ldbrhn ... bqṭyr’ "that he not oppress them" (Syriac dəbar baqəṭīrā "to oppress," lit. "to carry away with force").

- In the indicative: mn dy lšḥqh "whoever strikes him" (Syriac šəḥaq), mn dy lqrhy wl’ ldkrhy "whoever reads it and does not make mention of it", mn dlꜥwl mhk’ bmšn "whoever goes from here to Mesene", kwl mn dlcbwr ... wlktwb lꜥlyh "whoever passes ... and writes over".

- The preformative l- is employed identically in the Aramaic of Assur. The dialect of Hatra is thus further distinguished from Syriac (which uses an n- preformative) and also from Jewish Babylonian Aramaic, in which the use of the l- preformative for the indicative is not consistent.

Nominal Morphology

The distinction between the three states is apparent. As in Syriac, the masculine plural form of the emphatic state has the inflection -ē, written -’. The confusion of this form with that of the construct state may explain the constructions bn’ šmšbrk "sons of Š." and bn’ ddhwn "their cousins." The absolute state is scarcely used: klbn "dogs" and dkyrn "(that they may be) remembered."

Numbers

The ancient Semitic construction, according to which the counted noun, in the plural, is preceded by a numeral in the construct state, with an inversion of genders, is attested by one inscription: tltt klbn "three dogs." This same construction has been discovered in Nabataean: tltt qysrym "the three Caesars."

Syntax

As in Syriac, the analytical construction of the noun complement is common. The use of the construct state appears to be limited to kinship terms and some adjectives: bryk’ ꜥh’. In the analytical construction, the definite noun is either in the emphatic state followed by d(y) (e.g. ṣlm’ dy ... "statue of ...", spr’ dy brmryn’ "the scribe of (the god) Barmarēn") or is marked by the anticipatory pronominal suffix (e.g. qnh dy rꜥ’ "creator of the earth," ꜥl ḥyyhy d ... ’ḥyhy "for the life of his brother," ꜥl zmth dy mn dy ... "against the hair (Syriac zemtā) of whomever ..."). The complement of the object of the verb is also rendered analytically: ...l’ ldkrhy lnšr qb "do not make mention of N.", mn dy lqrhy lꜥdyn ktb’ "whoever reads this inscription."

Likewise, the particle d(y) can have a simple declarative meaning: ...l’ lmr dy dkyr lṭb "(a curse against whomever) does not say, 'may he be well remembered'" which can be compared with l’ lmr dy dkyr.

Vocabulary

Practically all of the known Hatran words are found in Syriac, including words of Akkadian origin, such as ’rdkl’ "architect" (Syriac ’ardiklā), and Parthian professional nouns such as pšgryb’ / pzgryb’ "inheritor of the throne" (Syriac pṣgryb’); three new nouns, which appear to denote some religious functions, are presumably of Iranian origin: hdrpṭ’ (which Safar compares with the Zoroastrian Middle Persian hylpt’ hērbed "teacher-priest"), and the enigmatic terms brpdmrk’ and qwtgd/ry’.

Final Observations

Many "irregularities" revealed by the texts of Hatra (e.g. the use of the emphatic state in place of the construct state, use of the construct state before the particle dy, inconsistent use of the matres lectiones, etc.) are found systematically in other Aramaic inscriptions throughout the duration of the Parthian Empire, between the third century BCE and the third century CE (previously, in part, at Kandahar, but primarily at Nisa, Avromân, Armazi, Tang-e Sarvak, etc.). We could therefore legitimately ask ourselves if, instead of speaking of "irregularities," which would be due, following each instance, to "scribal negligence," " archaisms of the language," and "orthographic indecision," etc., we should rather speak of the characteristics of these Aramaic dialects in their progressive developments (varying according to each region), which one could label "vernacular Aramaic" to distinguish them from "classical Aramaic."

References

- Beyer 1986, p. 32.

- Gzella 2015, p. 273.

Sources

- Beyer, Klaus (1986). The Aramaic Language: Its Distribution and Subdivisions. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783525535738.

- Beyer, Klaus (1998). Die aramäischen Inschriften aus Assur, Hatra und dem übrigen Ostmesopotamien. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783525536452.

- Caquot, André. "L'araméen de Hatra." Comptes rendus du groupe linguistique d'études Chamito-Sémitiques 9 (1960–63): 87-89.

- Gzella, Holger (2012). "Late Imperial Aramaic". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 574–586. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Gzella, Holger (2015). A Cultural History of Aramaic: From the Beginnings to the Advent of Islam. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004285101.

- Brugnatelli, Vermondo, "Osservazioni sul causativo in aramaico e in semitico nord-occidentale", Atti del Sodalizio Glottologico Milanese 25 (1984), p. 41-50.(text online)

External links

| Aramaic edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |