Arnold Thackray

Arnold Thackray (born 30 July 1939) is a science historian who is the founding president of the Chemical Heritage Foundation (now the Science History Institute), the Life Sciences Foundation, and Science History Consultants. He is an emeritus professor at the University of Pennsylvania.[1][2]

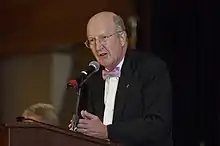

Arnold Wilfrid Thackray | |

|---|---|

Arnold Thackray, 2005 | |

| Born | July 30, 1939 northwest England |

| Nationality | United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Science historian |

| Known for | Founding President of the Chemical Heritage Foundation |

| Title | Joseph Priestley Professor Emeritus |

| Awards | Dexter Award |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | Cambridge University |

| Thesis | (1966) |

| Doctoral advisor | Mary Hesse |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | History of Science |

Early life and education

Thackray was born in northwest England on July 30, 1939. At age 10 he became a Foundation Scholar at the Manchester Grammar School, the first locus of the meritocracy under the leadership of Eric James, Baron James of Rusholme.[3] In 1960, he completed a B. Sc degree (1st Class Honors) in chemistry at Bristol University. He worked as a chemical engineer before enrolling in graduate school to pursue his interest in the history of science.[1] Thackray entered the doctoral program at Cambridge University in 1963, and studied under Mary Hesse, a leader in the field of Philosophy of Science.[1] He earned a Ph.D. degree in 1966.[4]

Academic and professional career

Following completion of his PhD, Thackray served on faculties at universities in the field of science history. Initially he was a research fellow at Churchill College, Cambridge University (he was the first student of Churchill College to be elected a Fellow).[5] In 1967 he accepted a one-year visiting lectureship at Harvard University. He joined the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania, in 1968.[6] When Harvard invited him to its regular faculty, professor Thackray chose instead to establish a novel Department of the History and Sociology of Science at Penn (the first university department to concentrate on modern science, technology, and medicine in their social context.) [5] Thackray has additionally held visiting professorships at Bryn Mawr College (1968 through 1973), the London School of Economics (1971-1972), the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (1978),[1] in addition to the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ (1980), and the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Palo Alto, CA (1974 and 1984).[6]

Thackray's research has focused on the rise of modern science, and the interactions between the scientific community and society as a whole. He has mentored twenty PhD students, authored numerous books and many scholarly articles. Additionally, he served as editor of the academic journals Isis (1978-1985) and Osiris (1984-1994), which cover the history of science. Thackray was president of the Society for Social Studies of Science from 1982 to 1983.[1]

In 1970 Thackray. as first chairman of the HSS Department, combined faculty from several areas of the university including the disciplines of history, philosophy, anthropology, sociology, chemistry, physics, biology, engineering, English, and American civilization.[7] During his 28 years at Penn, Thackray additionally served as curator of The Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection in the History of Chemistry.[8]

Chemical Heritage Foundation

A 1979-1980 task force led by historian John H. Wotiz[9] resulted in a recommendation to the American Chemical Society that it create a center for the history of chemistry.[10] In 1981, the American Chemical Society solicited proposals to develop such a center.[10] Thackray was already leading efforts to document the history of chemistry, and he proposed that ACS establish a center for the history of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania. To that end, Thackray enlisted the help of chemist Charles C. Price, who introduced Thackray to chemical industry executive and philanthropist John C. Haas. Haas helped elicit the interest of other influential figures in the chemical industry, especially DuPont Co. CEO Edward G. Jefferson and Dow Chemical Company CEO Paul Oreffice. The result was ACS's positive response to Thackray's proposal. In January 1982, the American Chemical Society established the Center for the History of Chemistry, initially housed at the University of Pennsylvania. ACS pledged $150,000 in funding for the center (to be distributed over three years), and the University of Pennsylvania pledged a matching $150,000.[11][12]

Thackray stated the objective of the Center for History of Chemistry to be "to discover and disseminate information about historical resources, and to encourage research, scholarship, and popular writing in the history of the chemical sciences and industries."[13]

Under Thackray's leadership, the center expanded its sponsorship and holdings and developed exhibits for the public. The American Institute of Chemical Engineers became a sponsor of the center with an agreement signed in 1983.[14] In 1987, the Center for History of Chemistry received a US $2 million endowment from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.[13] In 1987 CHOC became incorporated as the National Foundation for the History of Chemistry. In 1992, it was renamed the Chemical Heritage Foundation.[15]

During his tenure as president of the Chemical Heritage Foundation, Thackray initiated a plan for the building that housed the Chemical Heritage Foundation including a museum for the general public.[16] The project plan included a US $20million renovation of a United States Civil War era bank building, the First National Bank, in downtown Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The renovated building included a two-story museum for which the first floor was a permanent gallery, with the second floor being dedicated to temporary or traveling exhibits. The museum was designed by Ralph Appelbaurm of Ralph Appelbaum Associates.[17] It was created for people who are interested in learning about science in a social and historical context. The building re-design also included offices and archives. The project was complete in 2008.[16]

Under Thackray's guidance, CHF expanded its holding and sponsorship of scholarship and developed exhibits for the public. In 1997 Thackray led the launch of the Othmer Gold Medal at CHF, to honor individuals who have contributed to the advance of science through innovation, entrepreneurship, research, education, legislation, and philanthropy.[18] Thackray assembled a group of four sponsors for the award, including the American Chemical Society, the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, The Chemists' Club, and the Société de Chimie Industrielle (American Section).[19] In subsequent years, Thackray helped establish a series of awards, in partnership with various science organizations, to honor pioneers in fields ranging from materials science to biotechnology.[20] Thackray continued to serve as president of the Chemical Heritage Foundation until 2008, after which time he became Chancellor.

Life Sciences Foundation

After stepping down as president of CHF, Thackray relocated to Silicon Valley. There he founded the Life Sciences Foundation in 2010.[21] The idea for the foundation was conceived at a 2009 meeting between Thackray and four biotechnology industry leaders. The group reasoned that the biotechnology industry, then 40 years old, had a poorly documented history, and it was opportune to create the foundation to document the history before it was lost.[22] The Life Sciences Foundation came into existence in 2011, serving to document the stories of biotechnology's founders and increasing public awareness of the history of biotechnology through digital archives, hard copies of relevant historical items, and a free magazine.[23]

The Life Sciences Foundation subsequently merged with the Chemical Heritage Foundation in 2015,[24] which on February 1, 2018 was renamed the Science History Institute, to reflect its wider range of historical interests, from chemical sciences and engineering to the life sciences and biotechnology.[25]

Selected publications

- Arnold Thackray and Richard Ulrych, Building a Petrochemical Industry in Saudi Arabia, Obeikan Publishing, Riyadh, K.S.A. 2017 ((ISBN 978-603-02-4331-0)).

- Arnold Thackray, David C. Brock and Rachel Jones. Moore's Law: The Life of Gordon Moore, Silicon Valley's Quiet Revolutionary. Basic Books, 2015, ISBN 0465055648.

- Thackray, Arnold, ed. Private science: Biotechnology and the Rise of the Molecular Sciences. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998, ISBN 0812234286.

- Arnold Thackray, Jeffrey L. Sturchio, P.T. Carroll, R.F Bud. Chemistry in America 1876–1976: Historical Indicators. Vol. 5. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, ISBN 9027726620.

- Jack Morrell and Arnold Thackray. Gentlemen of science: Early years of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Oxford University Press, 1981, ISBN 0195203968.

- Thackray, Arnold. "Natural Knowledge in Cultural Context: The Manchester Mode." The American Historical Review 79.3 (1974): 672-709.

- Arnold Thackray, "Science: Has Its Present Past a Future?" in Roger H. Stewart (ed), HIstorical and Philosophical Perspectives of Science 1970

Awards and honors

Thackray was the 1983 recipient of the Dexter Award of the American Chemical Society for his work on the history of chemistry.[26] In 1984, Thackray received the George Sarton Memorial Lecturer Award for the meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science with a presentation entitled "The Historian's Calling in the Age of Science".[27] He was twice awarded fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (1971 and 1985).[1] Thackray is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Royal Historical Society and the Royal Society of Chemistry. In 2009, the American Chemical Society sponsored a symposium to honor Thackray.[28]

Personal life

Thackray became a citizen of the United States in 1981.[1]

Thackray has been married twice. His first wife was Barbara (née Hughes) Thackray, a physicist and teacher at the Shipley School in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.[29] Their children include Helen Thackray, a medical researcher and professor of pediatrics.[29][30] Thackray's second wife is Diana (née Schueler) Thackray.[31] Raising roses has been his hobby.[10]

References

- "Arnold Thackray (1939- )" (PDF). scs.illinois.edu. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- "Life Sciences Foundation--Telling the Story of Biotechnology" (https://www.biotech-now.org/business-and-investments/2012/04/the-life-sciences-foundation-%E2%80%93-telling-the-story-of-biotechnology)

- Barbara Celarent, American Journal of Sociology , 115 (2), 323-24, 2009; Michael Young, "The Rise of the Meritocracy", 1958

- Baykoucheva, Svetia (Fall 2008). "The Chemical Heritage Foundation: Past, Present, and Future". Chemical Information Bulletin. 60 (2): 10–13. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- http://acshist.scs.illinois.edu/awards/Dexter%20Papers/ThackrayDexterBioJJB.pdf

- Thackray, Arnold (1972). John Dalton; critical assessments of his life and science. Harvard University Press. p. About the author. ISBN 0674475259. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- "Department History". hss.sas.upenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- Manning, Kenneth. "A History of Chemistry". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- "John H. Wotiz (1919–2001)" (PDF). American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. American Chemical Society Dexter Awards. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- "Center for History of Chemistry Inaugural". CHOC News. 1 (3): 1–5. Summer 1983.

- Gussman, Neil. "The Power of John C. Haas's Good Name". Chemical Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2017.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Center for the History of Chemistry Inaugural" CHOC News. 1 (3): 1-5 Summer of 1983

- Carpenter, Ernest (November 16, 1987). "Chemistry History Center Receives Large Grant". Chemical & Engineering News. 65 (46): 6.

- "American Institute of Chemical Engineers Joins CHOC Endeavor". CHOC News. 2 (1): 1–3. Spring 1984.

- https://www.sciencehistory.org/history

- Arnaud, Celia Henry (October 27, 2008). "The Art of Science". Chemical and Engineering News. 86 (43): 34–36. doi:10.1021/cen-v086n043.p034.

- https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/magazine/making-modernity-a-gallery-preview

- "Othmer Gold Medal". Science History Institute. 2016-05-31. Retrieved 1 February 2018

- "Othmer Gold Medal". Science History Institute. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- https://www.sciencehistory.org/affiliate-partnership-awards

- "The Life Sciences Foundation – Telling the Story of Biotechnology". biotech-now.org. Biotechnology Innovation Organization. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- "Life Sciences Foundation Appoints Carl Feldbaum as New Board Chair", Life Sciences Foundation via Globe Newswire, San Francisco, July 2, 2014, retrieved July 19, 2015

- Morrison, Trista (February 2, 2012). "Life Sciences Foundation Looks to Capture History of Biotech". BioWorld Today. 23 (22): 1.

- Brubaker, Harold (October 15, 2015). "Chemical Heritage and Life Sciences foundations merging". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- Salisbury, Stephan (January 3, 2018). "Chemical Heritage Foundation is morphing into the Science History Institute". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- "Dexter Award for Outstanding Achievement in the History of Chemistry". scs.illinois.edu. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- "George Sarton Memorial Lecture". hssonline.org. History of Science Society. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- "The Heritage of Chemistry: A Symposium to Honor Arnold Thackray". oasys2.confex.com. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "Weddings; Helen Thackray, Lawrence Kessner". New York Times. May 19, 2002. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Jenkins, Kristina M. (November 30, 2015). "Helen Thackray '86: Developing Treatments through Biotechnology". Shipley News. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- "Obituary OSCAR J. SCHUELER". Fort Wayne newspaper. April 20, 2004. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

External links

- Science History Institute (formerly the Chemical Heritage Foundation)

- Department of History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania

- Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection