Automatic stabilizer

In macroeconomics, automatic stabilizers are features of the structure of modern government budgets, particularly income taxes and welfare spending, that act to dampen fluctuations in real GDP.[1]

The size of the government budget deficit tends to increase when a country enters a recession, which tends to keep national income higher by maintaining aggregate demand. There may also be a multiplier effect. This effect happens automatically depending on GDP and household income, without any explicit policy action by the government, and acts to reduce the severity of recessions.[2] Similarly, the budget deficit tends to decrease during booms, which pulls back on aggregate demand. Therefore, automatic stabilizers tend to reduce the size of the fluctuations in a country's GDP.

Induced taxes

Tax revenues generally depend on household income and the pace of economic activity. Household incomes fall and the economy slows down during a recession, and government tax revenues fall as well. This change in tax revenue occurs because of the way modern tax systems are generally constructed.

- Income taxes are generally at least somewhat progressive. This means that as household incomes fall during a recession, households pay lower rates on their incomes as income tax. Therefore, income tax revenue tends to fall faster than the fall in household income.

- Corporate tax is generally based on profits, rather than revenue. In a recession profits tend to fall much faster than revenue. Therefore, a company pays much less tax while having slightly less economic activity.

- Sales tax depends on the dollar volume of sales, which tends to fall during recessions.

If national income rises, by contrast, then tax revenues will rise. During an economic boom, tax revenue is higher and in a recession tax revenue is lower, not only in absolute terms but as a proportion of national income.

Some other forms of taxation do not exhibit these effects, if they bear no relation to income (e.g. poll taxes, export tariffs or property taxes).

Transfer payments

Most governments also pay unemployment and welfare benefits. Generally speaking, the number of unemployed people and those on low incomes who are entitled to other benefits increases in a recession and decreases in a boom. As a result, government expenditure increases automatically in recessions and decreases automatically in booms in absolute terms. Since output increases in booms and decreases in recessions, expenditure is expected to increase as a share of income in recessions and decrease as a share of income in booms.[3]

Incorporated into the expenditure multiplier

This section incorporates automatic stabilization into a broadly Keynesian multiplier model.

- MPC = Marginal propensity to consume (fraction of incremental income spent on domestic consumption)

- T = Marginal (induced) tax rate (fraction of incremental income that is paid in taxes)

- MPI = Marginal Propensity to Import (fraction of incremental income spent on imports)

Holding all other things constant, ceteris paribus, the greater the level of taxes, or the greater the MPI then the value of this multiplier will drop. For example, lets assume that:

- → MPC = 0.8

- → T = 0

- → MPI = 0.2

Here we have an economy with zero marginal taxes and zero transfer payments. If these figures were substituted into the multiplier formula, the resulting figure would be 2.5. This figure would give us the instance where a (for instance) $1 billion change in expenditure would lead to a $2.5 billion change in equilibrium real GDP.

Lets now take an economy where there are positive taxes (an increase from 0 to 0.2), while the MPC and MPI remain the same:

- → MPC = 0.8

- → T = 0.2

- → MPI = 0.2

If these figures were now substituted into the multiplier formula, the resulting figure would be 1.79. This figure would give us the instance where, again, a $1 billion change in expenditure would now lead to only a $1.79 billion change in equilibrium real GDP.

This example shows us how the multiplier is lessened by the existence of an automatic stabilizer, and thus helping to lessen the fluctuations in real GDP as a result from changes in expenditure. Not only does this example work with changes in T, it would also work by changing the MPI while holding MPC and T constant as well.

There is broad consensus among economists that the automatic stabilizers often exist and function in the short term.

Additionally, imports often tend to decrease in a recession, meaning more of the national income is spent at home rather than abroad. This also helps stabilize the economy.

Estimated effects

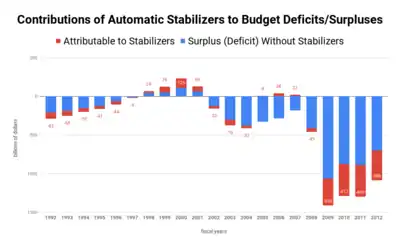

Analysis conducted by the Congressional Budget Office in 2013 estimated the effects of automatic stabilizers on budget deficits and surpluses in each fiscal year since 1960. The analysis found, for example, that stabilizers increased the deficit by 32.9% in fiscal 2009, as the deficit soared to $1.4 trillion as a result of the Great Recession, and by 47.6% in fiscal 2010. Stabilizers increased deficits in 30 of the 52 years from 1960 through 2012. In each of the five surplus years during the period, stabilizers contributed to the surplus; the $3 billion surplus in 1969 would have been a $13 billion deficit if not for stabilizers, and 60% of the 1999 $126 billion surplus was attributed to stabilizers.[4]

See also

References

- O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 399. ISBN 0-13-063085-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "What are automatic stabilizers and how do they work?". Tax Policy Center.

- Transfers are neither part of government expenditures nor consumption and do not contribute to GDP. Therefore, they can not be an automatic stabilizer, which contributes to GDP. See Principles of Economics, Bernanke, et al., 2016, page 413 https://www.amazon.com/Principles-Economics-Irwin-Robert-Frank/dp/0078021855

- The Effects of Automatic Stabilizers on the Federal Budget as of 2013, pp.6-7: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/43977_AutomaticStablilizers_one-column.pdf