Baengnyeongdo

Baengnyeong Island (sometimes spelled Baekryeong; Korean pronunciation: [pɛŋȵʌŋdo]) is a 45.8-square-kilometre (17.7 sq mi), 8.45-kilometre (5.25 mi) long and 12.56-kilometre (7.80 mi) wide island in Ongjin County, Incheon, South Korea, located near the Northern Limit Line.[1] The 1953 Korean Armistice Agreement which ended the Korean War specified that the five islands including Baengnyeong Island would remain under United Nations Command and South Korean control. This agreement was signed by both North Korea and the United Nations Command.[2] Since then, it has served as a maritime demarcation between North and South Korea in the Yellow Sea. It has a population of approximately 4,329.[3]

| Baengnyeongdo | |

| |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Baengnyeongdo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Paengnyŏngdo |

The meaning of its name is "white wing island", since the island resembles a flying ibis with its wings spread.[4]

Given its proximity to North Korea, it has served as a base for intelligence activity by South Korea. Numerous North Korean defectors have also boated here to escape economic and political conditions in their homeland. In the recent past there have been several naval skirmishes between the two countries in the area, and Kim Jong-Un threatened on 11 March 2013 to wipe it out.[5]

Natural monuments of South Korea #391–#393 are located on Baengnyeong Island.

Geography

Baengnyeong Island is the westernmost point of South Korea. Travel time by boat to the island from Incheon is about four hours.[6]

Changsan Cape in Ryongyon, North Korea, can be seen from Baengnyeong on clear days.

Environment

The area is also rich in oceanic fauna and bird diversity. The Chinese egret, which is considered to be one of the fifty rarest birds in the world, can be found here. The area hosts a nature reserve for spotted seals,[7] and they can be observed on the rocks and beaches.[6] Seals occasionally attract predators such as the great white shark into the area.[8][9] Finless porpoisees in adjacent waters are also curious and playful.[10] The Incheon Coast Guard has been investigating illegal whaling targeting minke whales in the area.[11][12][13]

Climate

| Climate data for Baengnyeongdo (1981–2010, extremes 2000–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

29.9 (85.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

33.5 (92.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

3.3 (37.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

10.4 (50.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

1.0 (33.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.7 (25.3) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.4 (0.7) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

0.5 (32.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−11.3 (11.7) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 11.6 (0.46) |

13.5 (0.53) |

23.2 (0.91) |

54.8 (2.16) |

78.9 (3.11) |

74.8 (2.94) |

201.1 (7.92) |

180.0 (7.09) |

113.9 (4.48) |

29.2 (1.15) |

27.3 (1.07) |

17.4 (0.69) |

825.6 (32.50) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 8.1 | 4.8 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 11.8 | 15.0 | 12.6 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 106.5 |

| Average snowy days | 11.1 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.2 | 12.3 | 36.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 63.9 | 62.7 | 64.5 | 65.0 | 69.4 | 77.6 | 85.7 | 81.4 | 73.9 | 67.4 | 63.5 | 63.9 | 69.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132.6 | 165.1 | 199.9 | 209.8 | 226.7 | 171.0 | 128.8 | 172.4 | 203.6 | 210.9 | 150.4 | 112.8 | 2,083.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 43.3 | 54.3 | 53.9 | 53.0 | 51.4 | 38.6 | 28.6 | 40.8 | 54.5 | 60.6 | 49.3 | 37.9 | 46.8 |

| Source: Korea Meteorological Administration[14][15][16] (percent sunshine and snowy days)[17] | |||||||||||||

Religion

Owing to the geographical location, Christianity went through Baengnyeong Island ahead of other Korean regions. After the Gabo Reform, Kim Seong-jin was exiled to this island, and the first church in Korea was established in 1896. There are ten churches on the island at the present time.

Neighboring islands

Two smaller islands nearby are Daecheong Island and the much smaller Socheong Island.

History

Korean War

During the Korean War, the USAF designated the airfield on Paengyong-do as K-53.

The island was defended by the West Coast Island Defense Task Unit composed of men of the 2d Korean Marine Corps Regiment under the direction of US Marines.[18]

In April 1951 Paengyong-do was used as a staging base for a mission to recover wreckage of a downed Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 near the Chongchon River. On 17 April 1951 a USAF Sikorsky H-19 carried a US/South Korean team to the crash site and they photographed the wreck and removed the turbine blades, combustion chamber, exhaust pipe and horizontal stabilizer. The overloaded helicopter then flew the team and samples back to Paengyong-do where they were transferred onto an SA-16 and flown south for evaluation.[19]

The USAF established a communications interception site on the island in mid-1951 which was used to intercept Chinese military communications.[20]

In December 1951 two Sikorsky H-5s of the USAF 3d Air Rescue Squadron were based on the island and would forward deploy daily to Chodo Airport to operate search and rescue missions before being permanently deployed to Chodo in January 1952. The H-5s were later replaced by the more capable Sikorsky H-19, two of which were based at Chodo and one on Paengyong-do.[21]

On 12 November 1952 several aircraft, believed to be Po-2s, bombed the base in a night attack causing minimal damage.[22]

In January 2010, an artillery duel between South Korean ships and North Korean land artillery occurred near Baengnyeong.[23][24]

March 2010 Baengnyeong incident

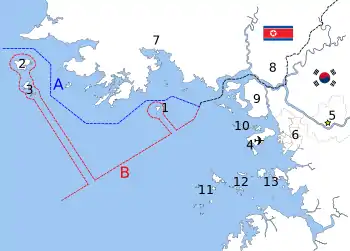

A: United Nations Command-created Northern Limit Line, 1953[26]

B: North Korea-declared "Inter-Korean MDL", 1999[27] The locations of specific islands are reflected in the configuration of each maritime boundary, including

- 1–Yeonpyeong Island

- 2–Baengnyeong Island

- 3–Daecheong Island

The South Korean naval vessel ROKS Cheonan sank near the island on 26 March 2010. The 1,200 ton vessel broke in two pieces with nearly half the crew dying (mainly in the stern section) and a little more than half surviving (mainly in the bow section). A multinational investigation concluded that a North Korean torpedo struck the ship.

References

- Yŏnʼguwŏn, Hanʼguk Kukpang (1999). "Defense white paper". Ministry of National Defense, Republic of Korea. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Text of the Korean War Armistice Agreement". FindLaw. 1953-07-27. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- "Baengnyeong-do" Galbijim

- "네이버 :: 백과사전". 네이버. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- Archived January 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- (in Korean)한국의 섬 (Islands of Korea) Archived 2012-03-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "멸종위기 물범, 왜 백령도로 올까". ecotopia.hani.co.kr.

- "백상아리, 백령도서 물범 공격장면 국내 첫 포착 - 민중의소리".

- "백상아리 물범 공격장면 첫 포착". Archived from the original on 2016-05-07.

- "백령도 어부들의 친구 쇠돌고래".

- "백령도 밍크고래 발견, 7.7m 초대형 크기 경악...가격대는?". www.newshankuk.com.

- "인천해경, 대형 밍크고래 통발에 걸려 죽은 채 발견". 9 October 2011.

- "백령도 밍크고래, 길이 7.7m 무게 4톤… '초대형 고래' 눈길 - 뉴스인사이드". 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- 평년값자료(1981–2010), 백령도(102) (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 기후자료 극값(최대값) 전체년도 일최고기온 (℃) 최고순위, 백령도(102) (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 기후자료 극값(최대값) 전체년도 일최저기온 (℃) 최고순위, 백령도(102) (in Korean). Korea Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Climatological Normals of Korea" (PDF). Korea Meteorological Administration. 2011. p. 499 and 649. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- Smith, Charles. U.S. Marines in the Korean War. Government Printing Office. p. 569. ISBN 9780160872518.

- Werrell, Kenneth (2005). Sabres over MiG Alley: the F-86 and the battle for air superiority in Korea. Naval Institute Press. pp. 95–6. ISBN 9781591149330.

- Werrell, p.104

- Werrell, p.113

- Werrell, p.110

- N. Korea fires into western sea border. Yonhap. January 27, 2010.

- Tang, Anne (January 29, 2010). "DPRK fires artillery again near disputed sea border: gov't". Xinhua.

- Ryoo, Moo Bong. (2009). "The Korean Armistice and the Islands," p. 13 (at PDF-p. 21). Strategy research project at the U.S. Army War College; retrieved 26 Nov 2010.

- "Factbox: What is the Korean Northern Limit Line?" Reuters (UK). November 23, 2010; retrieved 26 Nov 2010.

- Van Dyke, Jon et al. "The North/South Korea Boundary Dispute in the Yellow (West) Sea," Marine Policy 27 (2003), 143-158; note that "Inter-Korean MDL" is cited because it comes from an academic source Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine and the writers were particular enough to include in quotes as we present it. The broader point is that the maritime demarcation line here is NOT a formal extension of the Military Demarcation Line; compare "NLL—Controversial Sea Border Between S.Korea, DPRK, " People's Daily (PRC), November 21, 2002; retrieved 22 Dec 2010"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2012-03-09. Retrieved 2012-03-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

Further reading

- Malcom and Martz, White Tigers: My Secret War in North Korea, Brassey's. 1996