Banner blindness

Banner blindness is a phenomenon in web usability where visitors to a website consciously or unconsciously ignore banner-like information, which can also be called ad blindness or banner noise.

The term banner blindness was coined in 1998[1] as a result of website usability tests where a majority of the test subjects either consciously or unconsciously ignored information that was presented in banners. The information that was overlooked included both external advertisement banners and internal navigational banners, often called "quick links".

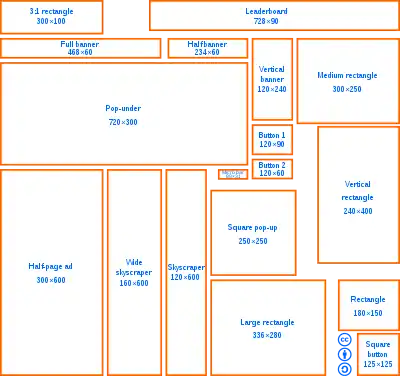

Banners have developed to become one of the dominant means of advertising. About 44% of the money spent on ads is wasted on ads that remain unviewed by website visitors. Some studies have shown that up to 93% of ads go unviewed.[2] The first banner ad appeared in 1994.[3] The average click-through rate (CTR) dropped from 2% in 1995 to 0.5% in 1998. After a relatively stable period with a 0.6% click-through rate in 2003,[4] CTR rebounded to 1% by 2013.[2]

This does not, however, mean that banner ads do not influence viewers. Website viewers may not be consciously aware of an ad, but it does have an unconscious influence on their behavior.[5] A banner’s content affects both businesses and visitors of the site.[3] The placement of ads is of the essence in capturing attention. Use of native advertisements and social media is used to avoid banner blindness.

Factors

User task

A possible explanation for the banner blindness phenomenon may be the way users interact with websites. Users tend to either search for specific information or browse aimlessly from one page to the next, according to the cognitive schemata that they have constructed for different web tasks. When searching for specific information on a website, users focus only on the parts of the page where they assume the relevant information will be, e.g. small text and hyperlinks.[6] A new methodological view has been taken into account, in a particular study conducted by Hervet et al., focusing on whether participants actually paid attention to the ads and on the relationship between their gaze behavior and their memories of these ads, investigating via eye-tracking analysis whether internet users avoid looking at ads inserted on a non-search website, and whether they retain ad content in memory. The study found that most participants fixated ads at least once during their website visit.[7] When a viewer is working on a task, ads may cause a disturbance, eventually leading to ad avoidance. If a user wants to find something on the web page and ads disrupt or delay his search, he will try to avoid the source of interference.[8]

Ad clutter

Increase in the number of advertisements is one of the main reasons for the trend in declining viewer receptiveness towards internet ads.[4] There exists a direct correlation between number of ads on a webpage and "ad clutter," the perception that the website hosts too many ads. Number of banner ads, text ads, popup ads, links, and user annoyance as a result of seeing too many ads all contribute to this clutter and a perception of the Internet as a platform solely for advertising.[8] An important determinant in users' viewing behavior is visual attention, which is defined as a cognitive process measured through fixations, i.e. stable gazes with a minimum threshold. As users can concentrate on only one stimulus at a time, having too many objects in their field of vision causes them to lose focus.[9] This contributes to behaviors such as ad avoidance or banner blindness.

Shared bandwidth

Advertising on the internet is different from advertising on the radio or television, so consumer response likewise differs. In the latter, the consumer cannot interrupt the ad except by turning it off or changing to a different channel or frequency. Conversely, websites are plagued with various components with different bandwidths, and as a banner ad occupies only a small percentage of a website, it cannot attract the user's complete attention.[8]

Major components

A customer's existing opinion of a product (in this case, banner ads) is the cognitive component of ad avoidance, which in turn influences attitudes and behavior. The customer will typically draw conclusions from his previous experiences, particularly the negative experiences of having clicked unpleasant ads in the past. His general feeling about an object is the effective component of the customer's ad avoidance; for example, if he is already averse to ads in general, this aversion will be bolstered by ads on a website. Finally, the behavioral component of ad avoidance consists of taking actions to avoid ads: scrolling down to avoid banner ads, blocking popups, etc.[8]

Familiarity

The behaviors of the viewers and their interests are important factors in producing CTR. Research shows, people in general dislike banner ads. In fact, some viewers don’t look at ads when surfing, let alone click on them. Therefore, when one gains familiarity with a web page, they begin to distinguish various content and their locations, ultimately avoiding banner like areas. By just looking at objects superficially, viewers are able to know objects outside their focus. And since the sizes of most banner ads fall in similar size ranges viewers tend to develop a tendency to ignore them without actually fixating on them.[8] Bad marketing and ads that are not correctly targeted make it more likely for consumers to ignore banners that aim at capturing their attention. This phenomenon called 'purposeful blindness' shows that consumers can adapt fast and become good at ignoring marketing messages that are not relevant to them.[10] It is a byproduct of inattentional blindness. Usability tests that compared the perception of banners between groups of subjects searching for specific information and subjects aimlessly browsing seem to support this theory - see study.[6] A similar conclusion can be drawn from the study of Ortiz-Chaves et al. dealt with how right-side graphic elements (in contrast to purely textual) in Google AdWords affect users' visual behavior. So the study is focused on people that search something. The analysis concludes that the appearance of images does not change user interaction with ads.[11]

Perceived usefulness

Perceived usefulness is a dominant factor that affects the behavioral intention to use the technology. The intention to click on an ad is motivated to a large extent by its perceived usefulness, relying on whether it shows immediately useful content. The perceived ease of use of banner ads and ease of comprehension help the perceived usefulness of ads by reducing the cognitive load, thereby improving the decision-making process.[12]

Location

The location of the banner has been shown to have an important effect on the user seeing the ad. Users generally go through a web page from top left to bottom right. So that suggests, having ads in this path will make them more noticeable. Ads are primarily located in the top or right of the page. Since viewers ignore ads when it falls into their peripheral vision, the right side will be ignored more. Banner ads just below the navigation area on the top will get more fixations. Especially when viewers are involved in a specific task, they might attend to ads on the top, as they perceive the top page as containing content. Since they are so much into the task, the confusion that whether the top page has content or advertisement, is enough to grab their attention.[13]

Animated ad

Users dislike animated ads since they tend to lose focus on their tasks. But this distraction may increase the attention of some users when they are involved in free browsing tasks. On the other hand, when they are involved in a specific task there is evidence that they not only tend to fail to recall the ads, but the completion time of tasks is increased, along with the perceived workload.[13] Moderate animation has a positive effect on recognition rates and brand attitudes. Rapidly animated banner ads can fail, causing not only lower recognition rates but also more negative attitudes toward the advertiser.[14] In visual search tasks, animated ads did not impact the performance of users but it also did not succeed in capturing more user fixations than static ones.[15] Animations signal the users of the existence of ads and lead to ad avoidance behavior, but after repetitive exposures, they induce positive user attitude through the mere exposure effect.[16]

Brand recognition

Recognition of a brand may affect whether a brand is noticed or not, and whether it is chosen or not. If the brand is unknown to the viewers, the location of such banner would influence it being noticed. On the other hand, if the brand is familiar to the viewers, the banner would reconfirm their existing attitudes toward the brand, whether positive or negative. That suggests a banner would have a positive impact only if the person seeing the banner already had a good perception of the brand. In other cases, it could dissuade users from buying from a particular brand in the future. If viewers have neutral opinion about such brands, then a banner could positively affect their choice, due to the "Mere-exposure effect", an attitude developed by people because of their awareness of a brand, which makes them feel less skeptical and less intimidated.[17]

Congruence

Congruity is the relationship of the content of the ad with the web content. There have been mixed results of congruity on users. Click through rates increased when the ads shown on a website were similar to the products or services of that website, that means there needs to be the relevance of ads to the site. Having color schemes for banner congruent to the rest of website does grab the attention of the viewer but the viewer tends to respond negatively to it, then one's whose color schemes were congruent.[18] Congruency has more impact when the user browses fewer web pages. When the ads were placed in e-commerce sports websites and print media, highly associated content led to more favorable attitudes in users towards ads. In forced exposure, like pop up ads, congruence improved memory. But when users were given specific tasks, incongruent ads grabbed their attention. At the same time, in a specific task, ad avoidance behaviors are said to occur, but which has been said to be mitigated with congruent ads. Free tasks attracted more fixations than an imposed task. The imposed task didn’t affect memory and recognition. Free task affected memory but not recognition. The combination of free task and congruence has been said to represent the best scenario to understand its impact since it is closer to real life browsing habits. The importance of congruency is that, even though it doesn’t affect recognition and memory, it does attract more fixations which is better than not seeing the ad at all.[19] In one such test conducted, a lesser known brand was recalled by a majority of people than an ad for a famous brand because the ad of the lesser known brand was relevant to the page.[20] The relevance of user's task and the content of ad and website does not affect view time due to users preconceived notion of the ads irrelevance to the task in hand.[21]

On the flip side, the congruency between the ad and the editorial content had no effect on fixation duration on the ad but congruent ads were better memorised than incongruent ads, according to the experiments conducted by Hervet et al.[22]

Personalization

Personalized ads are ads that use information about viewers and include them in it, like demographics, PII, purchasing habits, brand choices, etc. A viewer’s responsiveness could be increased by personalization. For example, if an ad contained his name, there is a better likelihood of purchase for the product. That is, it not only affects their intention but also their consequent behavior that translates into higher clicks with a caveat that they must have the ability to control their privacy settings. The ability to control the personalization and customizability has a great impact on users and can be called as a strong determinant of their attitudes towards ads. Personalized information increased their attention and elaboration levels. An ad is noticed more if it has a higher degree of personalization, even if it causes slight discomfort in users. Personalized ads are found to be clicked much more than other ads. If a user is involved in a demanding task, more attention is paid to a personalized ad even though they already have a higher cognitive load. On the other hand, if the user is involved in a light task, lesser attention is given to both types of ads. Also, personalized ad in some case was not perceived as a goal impediment, which has been construed to the apparent utility and value offered in such ads. The involvement elicited overcompensates the goal impediment.[2][23]

But such ads do increase privacy anxieties and can appear to be ‘creepy’. An individual who is skeptical about privacy concerns will avoid such ads. This is because users think that the personally identifiable information is used in order for these ads to show up and also suspect their data being shared with third party or advertisers. Users are okay with behavior tracking if they have faith in the internet company that permitted the ad. Though such ads have been found to be useful, users do not always prefer their behaviors be used to personalize ads. It also has a positive impact if it also includes their predilection for style, and timing apart from just their interests. Ads are clicked when it shows something relevant to their search but if the purchase has been made, and the ad continues to appear, it causes frustration.[2][23]

Contrasting to this, personalization enhanced recognition for the content of banners while the effect on attention was weaker and partially nonsignificant, in the studies conducted by Koster et al. overall exploration of web pages and recognition of task-relevant information was not influenced. The temporal course of fixations revealed that visual exploration of banners typically proceeds from the picture to the logo and finally to the slogan.[24]

Promotions

The traditional ways of attracting banner with phrases like “click here” etc., do not attract viewers. Prices and promotions, when mentioned in banner ads do not have any effect on the CTR. In fact, the absence of it had the most effect on impressions.[13] Display promotions of banner ads do not have a major impact on their perceived usefulness. Users assume that all ads signify promotions of some sort and hence do not give much weight to it.[12]

Recommendations

Native ads

The trick of effective ads is to make them less like banner ads.[25] Native ads are ads that are delivered within the online feed content. For example, short video ads played between episodes of a series, text ads in social feeds, graphics ads within mobile apps. The idea is the ads are designed as a part of general experiences in order to not move the user away from his task. Native ads are better in gaining attention and engagement than traditional ads. In an experiment conducted by infolinks, integrated native ads were seen 47% faster than banner ads and these areas had 451% more fixations than banner ads. Also, time spent by a user was 4000% more, which leads to better recall. Native ads are consumed the same way as the web content.[20] Viewability can be defined as a measure of whether an ad is visible on a site. Location and placement of an ad affect the viewability. Native advertisements have better viewability because they are better integrated with the website and have useful formats for customers. That’s one of the reasons why in-image ads have gained popularity. They are generally found in prime locations laid on top of website images which make them highly visible.[26]

Placement

Non-traditional placement of ads is important since users become trained in avoiding standard banner areas. But it should not disturb their experience of the content. Simple ads placed in a non-traditional and non-intrusive area have a better impact than rich media with usual placement.[20]

MILP (Mixed Integer Linear Programming) approach to tackle banner blindness is based is on the hypothesis that the exposure effect of banner changes from page to page. It proposes that if a banner is not placed on one web page and unexpectedly appears on the next, there would be more chances of the users noticing it. Data for the study was obtained from the clickstream. Then preprocessing was done to clean the data, remove irrelevant records, link it to specific users, and divide the user records into user sessions. Next, Markov chain was used to calculate the total exposure effect of a specific banner setting on a user. The theory of a mixed integer linear programming (MILP) is applied to select the location for the banner, where two situations were considered - one where a banner remained at one location on the webpages and the other where it frequently changed throughout the day. The result of the study showed that the difference between exposure effect of dynamic and static placement to be small, with exposure effect of dynamic being slightly more, and so choosing dynamic placement would not be a mistake. An approach such as MILP could be used by advertisers to find the most efficient location of banners.[27]

Relevance

If a website serves ads unrelated to its viewers' interests, about ¾ of viewers, experience frustration with the website.[28] Advertising efforts must focus on the user’s current intention and interest and not just previous searches. Publishing fewer, but more relative, ads is more effective. This can be done with the use of data analytics and campaign management tools to properly separate the viewers and present them ads with relevant content. Information about customers goals and aspirations could be gained through gamification tools which could reward them for providing valuable information that helps segment users according to their interests and helps effective targeting. Interactive ads could be used to make the customers aware of their products. Such tools could be quizzes, calculators, chats', questionnaires. This will further help in understanding the plans of potential customers. Ads should be presented as tips or expert advice, rather than just plain ads.[25]

Social media

All forms of advertising scored low in the trust factor study by the Nielsen Report on Global Trust in Advertising and Brand Messages from April 2012. But Facebook’s “recommendations from people I know” scored highest on the trust factor, with 92 percent of consumers having no problem believing this source. Also, brand websites scored higher than paid advertising but lower than social recommendations. The promotion of product or services through known people piqued interests of users as well as the views of ads much more effective than banner ads. This way advertisers are able to elicit and transfer feelings of safety and trust from friends to the ads shown, thereby validating the ads. The social pressure by the peer group has the ability to not make the users view ads but also encourage them to change attitudes, and consequent behavior in order to adapt to group customs.[29]

Businesses could interact with customers on social media, because not only they spend more time there, but also listen to recommendations from friends and family more than advertisers. Companies could reward customers for recommending products. Digital applications could include features that will allow them to share reviews or feedbacks on social media etc.[25]

See also

|

|

|

References

- Benway, J. P.; Lane, D. M. (1998). "Banner Blindness: Web Searchers Often Miss 'Obvious' Links" (PDF). Internet Technical Group, Rice University. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- O'Donnell, K., & Cramer, H. (2015, May). People's perceptions of personalized ads. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 1293-1298). ACM.

- Lapa, C. (2007). Using eye tracking to understand banner blindness and improve website design.

- Cho, C. H., & as-, U. O. T. A. A. I. A. (2004). Why do people avoid advertising on the internet?. Journal of advertising, 33(4), 89-97.

- Lee, J., & Ahn, J. H. (2012). Attention to banner ads and their effectiveness: An eye-tracking approach. International Journal of Electronic Commerce,17(1), 119-137.

- Pagendarm, M.; Schaumburg, H. (2001). "Why Are Users Banner-Blind? The Impact of Navigation Style on the Perception of Web Banners". Journal of Digital Information. 2 (1).

- Hervet, G.; Guerard, K.; Tremblay, S.; Chtourou, M. S. (2011). "Is Banner Blindness Genuine? Eye Tracking Internet Text Advertising". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 25 (5): 708–716. doi:10.1002/acp.1742.

- [null Drèze, X., & Hussherr, F. X. (2003). Internet advertising: Is anybody watching?. Journal of interactive marketing, 17(4), 8-23.]

- Djamasbi, S., Hall-Phillips, A., & Yang, R. R. (2013). An Examination of Ads and Viewing Behavior: An Eye Tracking Study on Desktop and Mobile Devices.

- de Ternay, Guerric (2016). "Purposeful Blindness: How Customers Dodge Your Ads". BoostCompanies. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- Ortiz-Chaves, L.; et al. (2014). "AdWords, images, and banner blindness: an eye-tracking study". El Profesional de la Información. 23 (3): 279–287. doi:10.3145/epi.2014.may.08.

- Idemudia, E. C., & Jones, D. R. (2015). An empirical investigation of online banner ads in online market places: the cognitive factors that influence intention to click. International Journal of Information Systems and Management, 1(3), 264-293.

- Resnick, M., & Albert, W. (2014). The impact of advertising location and user task on the emergence of banner ad blindness: An eye-tracking study. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 30(3), 206-219.

- Goldstein, D. G., Suri, S., McAfee, R. P., Ekstrand-Abueg, M., & Diaz, F. (2014). The economic and cognitive costs of annoying display advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(6), 742-752.

- Jay, C., Brown, A., & Harper, S. (2013). Predicting whether users view dynamic content on the world wide web. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 20(2), 9.

- Lee, J.; Ahn, J. H.; Park, B. (2015). "The effect of repetition in Internet banner ads and the moderating role of animation". Computers in Human Behavior. 46: 202–209. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.008

- Kindermann, H. (2016, July). A Short-Term Twofold Impact on Banner Ads. In International Conference on HCI in Business, Government and Organizations(pp. 417-426). Springer International Publishing.

- Robinson, H., Wysocka, A., & Hand, C. (2007). Internet advertising effectiveness: the effect of design on click-through rates for banner ads.International Journal of Advertising, 26(4), 527-541.

- Porta, M., Ravarelli, A., & Spaghi, F. (2013). Online newspapers and ad banners: an eye-tracking study on the effects of congruity. Online Information Review, 37(3), 405-423.

- Beating Banner Blindness: What the Online Advertising ... (n.d.). Retrieved October 23, 2016, from http://resources.infolinks.com/static/eyetracking-whitepaper.pdf

- Higgins, E., Leinenger, M., & Rayner, K. (2014). Eye movements when viewing advertisements. Frontiers in Psychology, 5.

- Hervet, G., Guérard, K., Tremblay, S., & Chtourou, M. S. (2011). Is banner blindness genuine? Eye tracking internet text advertising. Applied cognitive psychology, 25(5), 708-716.

- Bang, H., & Wojdynski, B. W. (2016). Tracking users' visual attention and responses to personalized advertising based on task cognitive demand.Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 867-876.

- Koster, M.; Ruth, M.; Hambork, K. C.; Kaspar, K. C. (2015). "Effects of Personalized Banner Ads on Visual Attention and Recognition Memory". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 29 (2): 181–192. doi:10.1002/acp.3080.

- "How to combat banner blindness in digital advertising". Marketing Tech News. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- "Banner Blindness, Viewability, Ad Blockers and Other Ad Optimization Tricks". Business 2 Community. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- Zouharová, M., Zouhar, J., & Smutný, Z. (2016). A MILP approach to the optimization of banner display strategy to tackle banner blindness. Central European Journal of Operational Research, 24(2), 473-488.

- "Online Consumers Fed Up with Irrelevant Content on Favorite Websites, According to Janrain Study | Janrain". Janrain. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- Margarida Barreto, A. (2013). Do users look at banner ads on Facebook?. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 7(2), 119-139.