Bath Oliver

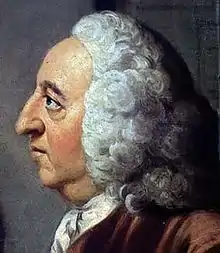

A Bath Oliver is a hard, dry biscuit or cracker[1] made from flour, butter, yeast and milk; often eaten with cheese. It was invented by physician William Oliver of Bath, Somerset around 1750, giving the biscuit its name.

| |

| Type | Biscuit |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | England |

| Region or state | Bath, Somerset |

| Created by | William Oliver |

| Main ingredients | Flour, butter, yeast, milk |

History

When Oliver died, he bequeathed to his coachman, Mr. Atkins, the recipe for the Bath Oliver biscuit, together with £100 and ten sacks of the finest wheat-flour. Atkins promptly set up his biscuit-baking business and became rich. Later the business passed to a man named Norris, who sold out to a baker called Carter, although it is possible that several Bath bakers were producing the biscuit in competition. During the nineteenth century the Bath Oliver biscuit recipe passed to James Fortt.[2] The company continued to produce the biscuit well into the second half of the twentieth century.

In October 2020 United Biscuits temporarily suspended production of Bath Olivers owing to COVID-19 disruption, without a prior announcement made. A run of production occurred in December 2020.[3]

In popular culture

The reference to Bath Oliver biscuits by Mary Norton in 'The Borrowers' 1952 evokes an Edwardian gentility: ". . . and it would comfort him to see, each evening at dusk, Mrs. Driver appear at the head of the stairs and cross the passage carrying a tray for Aunt Sophy with Bath Oliver biscuits and the tall, cut-glass decanter of Fine Old Pale Madeira."

Similarly, Bath Oliver biscuits seem to evoke a nostalgic, very English, idyll in the first chapter of Puck of Pook's Hill by Rudyard Kipling: "[the child heroes of the story] were not, of course, allowed to act on Midsummer Night itself, but they went down after tea on Midsummer Eve, when the shadows were growing, and they took their supper—hard-boiled eggs, Bath Oliver biscuits, and salt in an envelope—with them. [...] Everything else was a sort of thick, sleepy stillness smelling of meadow-sweet and dry grass." Also the biscuits are a favourite of Inspector Lestrade in the M. J. Trow mystery series.

| Look up Bath Oliver in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

In The Pound Era by Hugh Kenner, Ezra Pound associates the cracker with a receding world of manners when he remembers "Men of my time have witnessed 'parties' in London gardens where, as I recall it, everyone else (male) wore grey 'toppers' . . . Men have witnessed the dinner ceremony on flagships, where the steward still called it 'claret' and a Bath Oliver appeared with the cheese. (Stilton? I suppose it must have been Stilton.)"

In Hamlet, Revenge! (1937), part III, chapter one, mystery writer Michael Innes places Bath Olivers among the standard amenities of a country house bedroom in the 1930s. As the house steward explains to Inspector Appleby, "Two Bath Olivers, two Richtea, and two digestive in every room. Replenished daily and changed three times a week. The Bath Olivers go to Mr. Bagot [the butler]—he has a Partiality for Them—and the others to the servants' hall." In 'Rebecca' the narrator "steals" six Bath Olivers from the dining room sideboard before exploring Manderley by herself for the first time.

During World War II, the Crown Jewels were hidden in a secret chamber deep beneath Windsor Castle. The royal archivist pried out all of the major stones from the regalia and placed them inside a Bath Oliver tin so that most important part of the Crown jewels could be quickly removed and hidden, should the Germans invade.

Evelyn Waugh mentions Bath Oliver biscuits in his novel, Brideshead Revisited, as Sebastian Flyte and Charles Ryder nibble on the biscuits while indulging in a night of extravagant wine tasting.

References

- Osler, W.; Library, Osler (1969). Bibliotheca Osleriana: A Catalogue of Books Illustrating the History of Medicine and Science. Microfiche project - Hannah Institute of Medical Studies. MQUP. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-7735-9050-2. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- "Oliver". Bath Clinical Society. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- The Bath Oliver Preservation Society