Battleford Industrial School

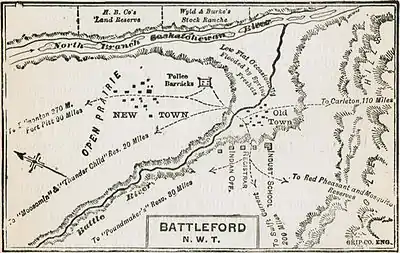

The Battleford Industrial School was a Canadian residential school for First Nations children in Battleford, Northwest Territories from 1883-1914. After its closure, many Indigenous children from around the Battlefords were sent to different schools in Saskatchewan, including Thunderchild Residential School at Delmas.

Old Government House, built in 1878–1879, was the seat of the Territorial Government from 1878 to 1883 of the Northwest Territories. It became one of the first modern Residential Schools in Canada, opened with the specific aim of assimilating Indigenous people into the society of the settlers. Battleford Industrial School was the first Residential School in Saskatchewan.

The Northwest Territories Act of 1875 had a significant effect on the region. The Lieutenant Governor was granted the authority to create electoral districts, appoint Justices of the Peace, issue liquor permits, direct the disposition of the North West Mounted Police, and report on the proceedings in territorial courts.[1]

The school was one established and subsidized as an early residential school, referred to as an "industrial school" and implemented using funding from the federal government of Canada. The senior officials of the Department of Indian Affairs arranged for various religious denominations to administer and operate the schools.[2] The federal government delegated responsibility for the residential school at Battleford to the Anglican Bishop of Saskatchewan.

History

Indigenous people damaged the interior of the school in the Looting of Battleford during the North West Rebellion of 1885. Later that year on November 27 the students were taken to Fort Battleford to witness the hanging of eight Indigenous men convicted of murder during the uprising.[3] Most of the students were from the Ahtahkakoop, Mistawasis and John Smith reserves.[4]

The school had less than 30 students when it first opened. They were taught trades related to agriculture, carpentry and blacksmithing. Academic courses were reading, writing and English.[4]

A new east wing was added in 1889.[5]

Later use of the building

The building then became the Seventh-day Adventist Battleford Academy from 1916 to 1931 with enrolments of between 114 and 160 students. A farm of 565 acres (229 ha) was attached.[6]

From 1932 to 1972 it was the Oblate House of Studies and the St. Charles Scholasticate (seminary) which closed in 1972. The Oblates left the building in 1984. Old Government House was designated a national historic site of Canada in 1973. The building was destroyed by fire in 2003.[7][8]

Cemetery

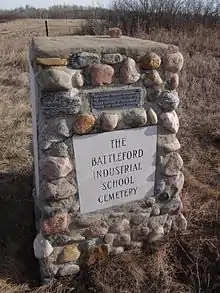

The Battleford Industrial School has a cemetery located seven-hundred metres due south of the site of the school. A 1974 excavation of the site revealed that seventy-two people were buried in the cemetery.[9] The Battleford Industrial School Cemetery was marked with a cairn, chain fences, and numbered grave markers on August 31, 1975.[10] The Battleford Industrial School cemetery was noted at page 119 in Volume 4 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada final reports:

When the Battleford school closed in 1914, Principal E. Matheson reminded Indian Affairs that there was a school cemetery that contained the bodies of seventy to eighty individuals, most of whom were former students. He worried that unless the government took steps to care for the cemetery, it would be overrun by stray cattle. Matheson had good reason for wishing to see the cemetery maintained: several of his family members were buried there. These concerns proved prophetic, since the location of this cemetery is not recorded in the available historical documentation, and neither does it appear in an internet search of Battleford cemeteries.[11]

Notable alumni

Alex Decoteau was born at Red Pheasant First Nation near the Battlefords. He became a student at the Battleford Industrial School following his father's death in 1891. He was an Olympic athlete and the first Indigenous police officer in Canada, joining the Edmonton Police Service in 1911. He died serving in World War I in 1917.[12] Edmonton has named a park and neighbourhood after Decoteau.

References

- Wasylow, Walter Julian. "History of Battleford Industrial School for Indians" (PDF). Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Walter Julian Wasylow (1972). "History of Battleford Industrial School for Indians" (PDF). Graduate Thesis. College of Education - University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- "Battleford Hangings". SASKATCHEWAN INDIAN v03 n07 p05. July 1972. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- James Rodger Miller (1996). Shingwauk's Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools. University of Toronto Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8020-7858-2.

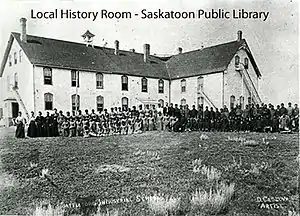

- "Students and staff in front of the Indian Industrial School". Saskatoon Public Library. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- J. Ernest Monteith (1983). "Battleford Academy" (PDF). The Lord is My Shepherd. Canadian Union Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Old Government House / Saint-Charles Scholasticate. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- Government House, Battleford. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- Colette Janelle Hopkins (2004). "THE FORGOTTEN CEMETERY OF THE ST. VITAL PARISH (1879-1885): A DOCUMENTARY AND MORTUARY ANALYSIS" (PDF). Thesis at page 170. University of Saskatchewan - Department of Archaeology. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Saskatchewan Indian (30 September 1975). "Burial Ground Re-Consecrated". Newspaper or Magazine. Saskatchewan Indian. Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). "Canada's Residential Schools: Missing Children and Unmarked Burials" (PDF). Government Report. McGill Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Edmonton Police Service (2016). "Legacy of Heroes - Who Was Alex Decoteau?". Comic Book. Edmonton Police Service. Retrieved 7 April 2017.