Belacqua

Belacqua is a minor character in Dante's Purgatorio, Canto IV. He is considered the epitome of indolence and laziness.

Most contemporary commentary on Belacqua is by way of Samuel Beckett's strong interest in him.

Dante's Belacqua

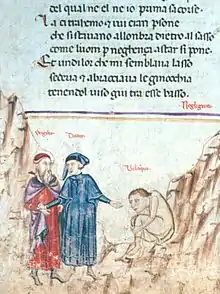

Belacqua is found by Dante and Virgil sitting in a fetal position under a large rock with other dead souls. They are condemned to wait in Ante-Purgatory as long as they waited in life to repent and turn to God. Dante recognizes Belacqua as his friend, and has a witty exchange with him.

"Belacqua" was identified by early commentators as the nickname of Duccio di Bonavia, a Florentine musician, a maker of musical instruments, and a friend of Dante. He had a reputation for extreme laziness. Records exist that state he was alive in 1299 and dead in 1302. Since Dante's visit to Purgatory is set in 1300, it is assumed di Bonavia had just died.

Beckett's Belacqua

Samuel Beckett, whose favorite reading was Dante, closely identified with Belacqua and his indolence.

Beckett introduced ‘Belacqua Shuah’ as the main character in his first novel Dream of Fair to Middling Women. Unpublishable at the time, Beckett tried again, with More Pricks Than Kicks, a collection of ten interrelated short stories on the life and death of Belacqua, and this was published, although a very poor seller. Beckett makes the Dante connection explicit in the first story, ‘Dante and the Lobster’: Belacqua is studying Dante. An eleventh story, ‘Echo's Bones’ was unpublishable at the time. It tells of the indolent afterlife of Belacqua, trying to sit in a fetal position as much as possible, and being interrupted by visitors.

In later fiction, Beckett would sometimes refer to Dante's Belacqua. The title character of Murphy has a Belacqua fantasy. The narrator of How It Is describes one of his sleeping postures in terms of Belacqua. Company's narrator refers to the ‘old lutist cause of Dante's first quarter-smile’ and wonders if the old lutist has made it to Paradise by now. At the beginning of Molloy, the narrator, who is doing nothing but watching passers, likens himself to Belacqua or Sordello as he crouches to avoid being detected.

General references

Dante related

- George D. Economon (2011). "Belacqua". In Richard Lansing (ed.). The Dante Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 9781136849725.

- Ralph Hayward Keniston (1912). "The Dante Tradition in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries". Annual Reports of the Dante Society (31): 45. JSTOR 40178473.

- Fernando Salsano (1970). "Belacqua". In Bosco, Umberto; Petrocchi, Giorgio (eds.). Enciclopedia Dantesca (in Italian). Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 2014-09-16.

- Charles S. Singleton (1973). The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri. volume II part 2. Princeton University Press. pp. 88–91. ISBN 9780691019109.

- Paget Toynbee (1898). "Belacqua". A Dictionary of Proper Names and Notable Matters in the Works of Dante. Oxford at the Clarendon Press. p. 74.

Beckett related

- Julie Campbell (2001). ""Echo's Bones" and Beckett's Disembodied Voices". Samuel Beckett Today/Aujourd'hui. 11: 454–60. JSTOR 25781397.

- Daniela Caselli (2000). ""The Florentia Edition in the Ignoble Salani Collection": A Textual Comparison". Journal of Beckett Studies. New Series. 9 (2): 1–20. doi:10.3366/jobs.2000.9.2.2.

- Daniela Caselli (2006). Beckett's Dantes: Intertextuality in the fiction and criticism. Manchester University Press.

- Daniela Caselli (2013). "Italian Literature". In Anthony Uhlmann (ed.). Samuel Beckett in Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 241–252. ISBN 9781107017030.

- Caroline Mannweiler (2010). "Becketts Belacqua: Lob und Tadel einer Anti-Haltung". In Klaus Ley (ed.). Dante Alighieri und sein Werk in Literatur, Musik und Kunst bis zur Postmoderne. Tübingen: Francke. pp. 151–68.

- Walter A. Strauss (Summer 1959). "Dante's Belacqua and Beckett's Tramps". Comparative Literature. 11 (3): 250–261. doi:10.2307/1768359. JSTOR 1768359.