Bikenibeu

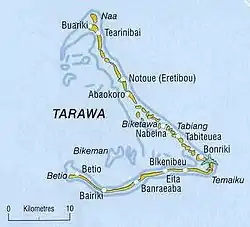

Bikenibeu is a settlement in Kiribati. It is located close to the southeastern corner of the Tarawa atoll, part of the island country of Kiribati. It is part of a nearly continuous chain of settlements along the islands of South Tarawa, which are now linked by causeways. The low-lying atoll is vulnerable to sea level rise. Rapid population growth has caused some environmental problems. Kiribati's main government high school, King George V and Elaine Bernachi School, is located in Bikenibeu,[2] as well as the Ministries of Environment and Education.

Bikenibeu | |

|---|---|

Cultural Museum in Bikenibeu | |

| |

Bikenibeu  Bikenibeu | |

| Coordinates: 1.367°N 173.126°E | |

| Country | |

| Island group | Gilbert Islands |

| Atoll | Tarawa |

| Locality | South Tarawa |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.81 km2 (0.70 sq mi) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 6,568 |

| • Density | 3,600/km2 (9,400/sq mi) |

Location

Bikenibeu is one of the three main urban centres in South Tarawa, the others being Betio and Teaoraereke.[2] Starting in 1963, causeways began to be built between the islands of the atoll to make communications easier.[3] The causeways connected Bairiki to Bikenibeu by 1963, and extended from Bikenibeu to Bonriki by 1964, when flights began from the new airport to Fiji.[4]

Bikenibeu island lies between the Tarawa Lagoon to the north, with a maximum depth of 25 metres (82 ft), and the Pacific Ocean to the south, with a depth of up to 4,000 metres (13,000 ft).[5]

The island has been built from sediments from the lagoon.[6]

The process of soil accumulation is driven by the dominant easterly trade winds, and can be reversed during extended periods of westerly winds during El Niño–Southern Oscillations.[7]

Bikenibeu is an average of 3.25 metres (10.7 ft) above sea level on the ocean side, and 2.38 metres (7 ft 10 in) at the lagoon side.[8] Tidal flats on the ocean side extend for 160 metres (520 ft).[5]

ACLR (Accelerated Sea-Level Rise) is a serious concern. In a scenario where a sea level rise of .5 metres (1 ft 8 in) occurs, 71% of Bikenibeu would be flooded by a spring high tide. With a rise of .95 metres (3 ft 1 in) the tide would flood the entire island.[7]

As of 2000, the lagoon away from the shore was still relatively free of human contaminants.[9] However, the causeways linking the islands of South Tarawa have contributed to increasing pollution in the lagoon.[10]

The coral reefs provide natural protection to the coastline, important if sea levels rise.[7] A 2000 report noted large numbers of dead corals on the reef flats on the ocean side, apparently due to past discharges of sewerage. The causeways and land reclamation have also affected the reef environment.[11]

Other environmental problems caused by the growing population include over-fishing and reduction of useful plants and trees such as coconuts.[10]

Population

As of 1996, South Tarawa was almost continuously settled from the Bonriki International Airport through Bikenibeu to Bairiki in the west.[2]

In 1996, there were 4,885 people living on Bikenibeu island, with an area of 1.81 square kilometres (0.70 sq mi).[12]

As of 2005, the population was 6,170, living in 831 households.[13]

By 2010, the population had grown to 6,568.[1]

Migration and population pressure has caused a number of families to build homes on vacant land, becoming squatters.[14]

Facilities

In 1953, the decision was made to build facilities for the medical and education departments at Bikenibeu.[3]

A permanent hospital was built at Bikenibeu in 1956.[15]

Several ministries are based in the settlement. These include the Ministry of Education,[16] and the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Agricultural Development. The Ministry of Health and the nursing school are now housed in a new hospital in the neighbouring village of Nawerewere that was built in 1991 with aid from Japan.[10] This is the country's main hospital for medicine, surgery and anaesthetics, paediatrics, obstetrics and gynaecology, and psychiatry, and includes a laboratory, pharmacy and x-ray facility.[17] The general hospital has 160 beds. There is also a dental clinic.[18]

A power plant in Bikenibeu provides a mains electrical service;[2] the hospital at Nawerewere is supplied by the grid, and also had back-up power for essential services.

After a cholera epidemic in 1977 a reticulated sewerage system was installed, using sea water as the conveyance medium.[lower-alpha 1][10]

The King George V school was moved from temporary buildings at Abemama and established in a new building in Bikenibeu in June 1953.[20]

The Elaine Bernacchi Secondary School for girls opened 1959, named after the wife of the Resident Commissioner at the time, Michael Bernacchi.[21]

Also in the late 1950s, the Tarawa Teacher's College began to operate in Bikenibeu.

The two Bikenibeu secondary schools began to be integrated from 1965.[3] They are now a single co-educational school run by the government – KGV/EBS.[10]

Education in Kiribati is compulsory and free from age six to fourteen (year 9).

Church missions provide secondary education for year 10–13 pupils who fail to be admitted to KGV/EBS.[22]

Preachers of the Baháʼí Faith came to Kiribati in 1954, setting up their first centre in Abaiang. The Baháʼí Faith was recognised as a legal religion in 1955.[23] The Baháʼís moved to Bikenibeu in 1957, where they established a centre and housing for resident or travelling teachers. In 1967, the Kiribati Baháʼís set up an independent National Spiritual Assembly with headquarters in Bikenibeu. The Baháʼí Faith in Kiribati claimed 4,000 members in 1985.[24]

There is also a Catholic church dedicated to Saint Peter, and a number of smaller Catholic and Protestant churches and maneaba.

Located on the lagoon side of the island, Otintaai is the only hotel in Bikenibeu with modern amenities.[25]

Te Umanibong, a cultural centre that features local artefacts, is open weekdays.[26]

Bikenibeu Post Office opened on 1 July 1958.[27]

Notable people

- Bikenibeu Paeniu – Prime Minister of Tuvalu for two terms

References

Notes

- Use of seawater to transport sewage can be a viable and cost-effective option in island communities such as Tarawa where potable water is in short supply – and even in larger cities such as Hong Kong.[19]

Citations

- Kiribati Census 2010.

- "6. South Tarawa" (PDF). Office of Te Beretitent – Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series. 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Talu & 24 others 1984, p. 99.

- MacDonald 2001, p. 177.

- Martin 2000, p. 152.

- Schofield 1977, p. 533.

- Chaoxiong 2001, p. 6.

- Chaoxiong 2001, p. 5.

- Martin 2000, p. 160.

- Trease 1993, p. 127.

- Hopley 2011, p. 64.

- Martin 2000, p. 115-116.

- Kiribati 2005 Census, p. 2.

- Mason & Hereniko 1987, p. 208.

- Talu & 24 others 1984, p. 100.

- "About Us." Ministry of Education (Kiribati). Retrieved on 6 July 2018.

- Trease 1993, p. 251.

- Hinz & Howard 2006, p. 348.

- Wells & Rose 2006, p. 1.

- MacDonald 2001, p. 169.

- Trease 1993, p. 135.

- Trease 1993, p. 242.

- Finau, Ieuti & Langi 1992, p. 101.

- Finau, Ieuti & Langi 1992, p. 102.

- Thompson 2002, p. 19.

- Hunt 2000, p. 239.

- Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

Sources

- Chaoxiong, He (December 2001). "Assessment of the Vulnerability of Bairiki and Bikenibeu, South Tarawa, Kiribati, to Accelerated Sea-Level Rise" (PDF). SOPAC Secretariat. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finau, Makisi; Ieuti, Teeruro; Langi, Jione (1992). Island Churches: Challenge and Change. [email protected]. ISBN 978-982-02-0077-7. Retrieved 20 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hinz, Earl R.; Howard, Jim (1 May 2006). Landfalls of Paradise: Cruising Guide to the Pacific Islands. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3037-3. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hopley, David (19 January 2011). Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs: Structure, Form and Process. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-2638-5. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunt, Errol (April 2000). South Pacific. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-0-86442-717-5. Retrieved 20 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Kiribati 2005 Census of Population and Housing: Provisional Tables" (PDF). Prism. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- "Kiribati Census 2010 Volume 1" (PDF). Statistics office, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Government of Kiribati. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2014.

- MacDonald, Barrie (2001). Cinderellas of the Empire: Towards a History of Kiribati and Tuvalu. [email protected]. ISBN 978-982-02-0335-8. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martin, Ronald E. (2000). Environmental Micropaleontology: The Application of Microfossils to Environmental Geology. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-46232-0. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mason, Leonard Edward; Hereniko, Pat (1987). In Search of a Home. [email protected]. ISBN 978-982-01-0016-9. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schofield, J.C. (1977). "Effect of Late Holocene Sea-Level Fall on Atoll Development". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. Royal Society of New Zealand. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Talu, Sr Alaima; 24 others (1984). Kiribati: Aspects of History. [email protected]. ISBN 978-982-02-0051-7. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Chuck (1 December 2002). Twenty-five Best World War 2 Sites. ASDavis Media Group. ISBN 978-0-9666352-6-3. Retrieved 20 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trease, Howard Van (1993). Atoll Politics: The Republic of Kiribati. [email protected]. ISBN 978-0-9583300-0-8. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wells, C.D.; Rose, P.D. (2006). "Treating Saline Domestic Wastewater in an Integrated Algal Ponding System (IAPS)" (PDF). eWISA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)