Billy Frank Jr.

Billy Frank Jr. (March 9, 1931 – May 5, 2014) was a Native American environmental leader and treaty rights activist. A Nisqually tribal member, Frank led a grassroots campaign for fishing rights on the tribe's Nisqually River, located in Washington state, in the 1960s and 1970s. As a lifelong activist and the chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission for over thirty years, Frank promoted cooperative management of natural resources.[1]

Billy Frank Jr. | |

|---|---|

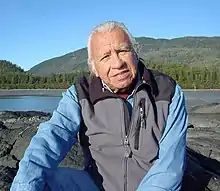

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Billy Frank Jr. at the 2012 Ecotrust Indigenous Leadership Award ceremony in Portland, Oregon | |

| Born | March 9, 1931 Nisqually, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | May 5, 2014 (aged 83) Nisqually, Washington, U.S. |

| Nationality | Nisqually Indian |

| Occupation | Native American rights activist |

| Years active | 1960-2014 |

| Known for | Advocate of tribal fishing rights, leader of "fish-ins" during Fish Wars |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom |

Frank advocated for tribal fishing rights during the Fish Wars by hosting a series of “fish-ins” where his actions culminated in the Boldt Decision, which affirmed that Washington state tribes’ were entitled to half of each year’s fish harvest.[2]

Frank was posthumous awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in November 2015.[3] The Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge was renamed in his honor in December 2015.[4][5][6] Billy Frank Jr. was and continues to be an important bridge between Western and Native American societies in a time where environmental sustainability affects us all, regardless of differences in cultural background and beliefs.[7]

Early life

Billy Frank Jr. was born in Nisqually, Washington in 1931 to Willie and Angeline Frank. His father Willie, born Qui-Lash-Kut, lived to 102 years and his mother Angeline lived into her 90's.[8] He grew up on six acres on the Nisqually River known as Frank’s Landing, land purchased by his father "after the expansion of an Army base nearby drove them from their reservation."[9] His formal education ended after he finished the ninth grade in Olympia and went on to work in construction by day, fishing at night.[8]

In 1952, Frank joined the US Marine Corps at age 21 and served for two years.[8]

Activism

Frank was first arrested at age fourteen while fishing on the Nisqually River,[2] following a run in with game wardens in 1945. The teenager had been fishing for salmon, and, while emptying his net, he was accosted by two wardens who shoved his face into the mud as he struggled. The tensions from the declining fish populations in the 1940s had begun to boil over. The unregulated commercial boats and development of hydroelectric equipment had begun to take its toll on the salmon, and the white sportsmen laid the blame at the Native's feet. As the numbers of salmon continued to decline, in 1965 the pressure between Native and non-Native fishermen turned violent as women and children of the Nisqually tribe protested alongside the fishermen and several Natives were bloodied. For Frank, the battle for the salmon was personal, treaty rights had to be recognized for not only the Native right to fish a guaranteed number of the salmon population, but the right to maintain ecosystems that would continue to guarantee a healthy yield of fish year after year.[10][11]

The tribal nations in western Washington reserved the right to fish at all their usual and accustomed places in common with all citizens of the United States, and to hunt and gather shellfish in treaties with the U.S. government negotiated in the mid-1850s.[12] But when tribal members tried to exercise those rights off-reservation they were arrested for fishing in violation of state law.

In 1963, Frank began a long partnership with Native Rights activist and strategist Hank Adams.[13]Frank was arrested more than 50 times in the Fish Wars of the 1960s and 1970s because of his intense dedication to the treaty fishing rights cause. The tribal struggle was taken to the courts in U.S. v. Washington, with federal judge George Hugo Boldt issuing a ruling in favor of the native tribes in 1974. The Boldt Decision established the 20 treaty Indian tribes in western Washington as co-managers of the salmon resource with the State of Washington, and re-affirmed tribal rights to half of the harvestable salmon returning to western Washington.[14]

What started as a war over numbers morphed into a fight for conservation and habitat protection. Because of the trail blazing achieved by Frank's activism, tribes worked more closely with government officials in a joint effort to conserve natural resources. The foundations established by Frank, in conjunction with the acknowledgement of tribal rights as defined in their treaties with the United States of America, encouraged the development of an inter-government partnership between the two groups.[15][16][17]

Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

The Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission (NWIFC) was created in 1975 to support the natural resource management activities of the 20 treaty Indian tribes in western Washington. The NWIFC is based in Olympia, Washington, with satellite offices in Forks and Mount Vernon. Frank chaired the NWIFC since for over thirty years, from 1981 until his death on May 5, 2014.[18] The commission's 65-person staff supports member tribes in efforts ranging from fish health to salmon management planning and habitat protection. The NWIFC serves as a forum for tribes to address issues of mutual concern, and as a mechanism for tribes to speak with a unified voice in Washington, D.C.[14]

Titles

Frank has held several different titles his career.

- 1975–1988 - Fisheries Manager, Nisqually Indian Tribe.

- 1977, 1981–2014 - Chairman, Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission (NWIFC).

- 1977–2014 - Commissioner, Medicine Creek Treaty Area in the NWIFC.

- 1996–2003 - Member of Board of Trustees of The Evergreen State College.[19]

- 2003–2014 - Founding Board Member, Salmon Defense (a 501(c)3 whose mission is to "protect and defend Pacific Northwest salmon and salmon habitat.")

Honors and awards

- Common Cause Award (1985), for his human rights efforts

- Washington State Environmental Excellence Award (1987), on behalf of the State Ecological Commission and other tribes.

- American Indian Distinguished Service Award (1989)

- Martin Luther King Jr. Distinguished Service Award (1990), for humanitarian achievement

- Albert Schweitzer Prize for Humanitarianism (1992)[9]

- American Indian Visionary Award (2004), from Indian Country Today for "exceptional contributions to Indian American freedom."[19]

- Dan Evans Stewardship Award (2006)

- Native American Leadership Award (2011), from National Congress of American Indians

- Seattle Aquarium Medal (2011)

- Washington state Medal of Merit (2015)[20]

- In November 2015, Frank was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in a ceremony at the White House.[21]

References

- "Interior Secretary Norton Honors Cooperative Conservation Partnership at Nisqually River Watershed." Interior Department. 25 Aug. 2005

- Lerman, Rachel (November 16, 2015). "Billy Frank Jr. and Ruckelshaus to receive Medal of Freedom". Seattle Times. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- "President Obama Names Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". The White House. November 16, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- "Statement by the Press Secretary on H.J.Res. 76, H.R. 2270, H.R. 2297, H.R. 2693, H.R. 2820, H.R. 3594, H.R. 3831, H.R. 4246, S. 614, S. 808, S. 1090 and S. 1461" (Press release). White House Press Secretary. December 18, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- "Nisqually wildlife refuge to be renamed for activist Billy Frank Jr". The Seattle Times. December 14, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- Connelly, Joel (December 14, 2015). "Senate passes legislation to rename Nisqually Wildlife Refuge for Billy Frank Jr". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- Nielsen, Larry A. (2017). Nature's Allies: Eight Conservationists who Changed our World. Washington DC: Island Press. p. 149. ISBN 9781610917957.

- Marritz, Robert O. (March 10, 2009). "Frank, Billy Jr. (1931-2014)". History Link. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- Yardley, William (May 9, 2014). "Billy Frank Jr., 83, Defiant Fighter for Native Fishing Rights (Published 2014)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- Reyes, Lawney (2016). The Last Fish War: Survival on the Rivers. Seattle, Washington: Chin Music Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1634050029.

- Wilkinson, Charles (2000). Messages from Frank's Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295985933.

- http://nwtreatytribes.org/treaties/

- Mapes, Lynda V. (December 28, 2020). "Hank Adams, champion for American Indian sovereignty, treaty rights, dies at 77". Seattle Times. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- "Billy Frank Jr." Institute for Tribal Government. Portland State University. 2 Dec. 2008 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 4, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Preserving Salmon Habitat Paramount 30 Years After Boldt Decision". Native Voice. 3 (4): D3. March 2004.

- Brown, Jovana (Autumn 1994). "Treaty Rights Twenty Years After the Boldt Decision". The Wicazo SA Review. 10 (2): 1–16. doi:10.2307/1409130. JSTOR 1409130.

- Blumm, Michael (March 2017). "Indian Treaty Fishing Rights and the Environment: Affirming the Right to Habitat Protection and Restoration". Washington Law Review. 92 (1): 1–38 – via HeinOnline Law Journal Library.

- Welch, Craig (May 5, 2014). "Billy Frank Jr., Nisqually elder who fought for treaty rights, dies". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- "Biography- Billy Frank Jr." American Indian Law. The Evergreen State College. 3 Dec. 2008 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved December 4, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "State Presents Medal of Merit, Medal of Valor". Washington Secretary of State's Office. March 18, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- Phil Helsel - "Obama honoring Spielberg, Streisand and more with medal of freedom," NBC News, November 24, 2015. Retrieved 2015-11-25

Further reading

Trova Heffernan, Where the Salmon Run: The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr., University of Washington Press, 2013. ISBN 9780295993409.

Charles Wilkinson, Messages from Frank's Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way, University of Washington Press, 2006. ISBN 9780295985930.