Bistability

In a dynamical system, bistability means the system has two stable equilibrium states.[1] Something that is bistable can be resting in either of two states. An example of a mechanical device which is bistable is a light switch. The switch lever is designed to rest in the "on" or "off" position, but not between the two. Bistable behavior can occur in mechanical linkages, electronic circuits, nonlinear optical systems, chemical reactions, and physiological and biological systems.

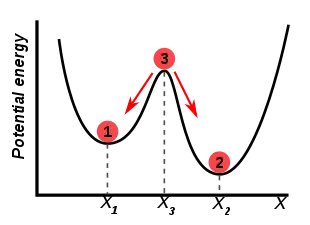

In a conservative force field, bistability stems from the fact that the potential energy has two local minima, which are the stable equilibrium points.[2] These rest states need not have equal potential energy. By mathematical arguments, a local maximum, an unstable equilibrium point, must lie between the two minima. At rest, a particle will be in one of the minimum equilibrium positions, because that corresponds to the state of lowest energy. The maximum can be visualized as a barrier between them.

A system can transition from one state of minimal energy to the other if it is given enough activation energy to penetrate the barrier (compare activation energy and Arrhenius equation for the chemical case). After the barrier has been reached, the system will relax into the other minimum state in a time called the relaxation time.

Bistability is widely used in digital electronics devices to store binary data. It is the essential characteristic of the flip-flop, a circuit which is a fundamental building block of computers and some types of semiconductor memory. A bistable device can store one bit of binary data, with one state representing a "0" and the other state a "1". It is also used in relaxation oscillators, multivibrators, and the Schmitt trigger. Optical bistability is an attribute of certain optical devices where two resonant transmissions states are possible and stable, dependent on the input. Bistability can also arise in biochemical systems, where it creates digital, switch-like outputs from the constituent chemical concentrations and activities. It is often associated with hysteresis in such systems.

Mathematical modelling

In the mathematical language of dynamic systems analysis, one of the simplest bistable systems is

This system describes a ball rolling down a curve with shape , and has three equilibrium points: , , and . The middle point is unstable, while the other two points are stable. The direction of change of over time depends on the initial condition . If the initial condition is positive (), then the solution approaches 1 over time, but if the initial condition is negative (), then approaches −1 over time. Thus, the dynamics are "bistable". The final state of the system can be either or , depending on the initial conditions.[3]

The appearance of a bistable region can be understood for the model system which undergoes a supercritical pitchfork bifurcation with bifurcation parameter .

In biological and chemical systems

Bistability is key for understanding basic phenomena of cellular functioning, such as decision-making processes in cell cycle progression, cellular differentiation,[5] and apoptosis. It is also involved in loss of cellular homeostasis associated with early events in cancer onset and in prion diseases as well as in the origin of new species (speciation).[6]

Bistability can be generated by a positive feedback loop with an ultrasensitive regulatory step. Positive feedback loops, such as the simple X activates Y and Y activates X motif, essentially links output signals to their input signals and have been noted to be an important regulatory motif in cellular signal transduction because positive feedback loops can create switches with an all-or-nothing decision.[7] Studies have shown that numerous biological systems, such as Xenopus oocyte maturation,[8] mammalian calcium signal transduction, and polarity in budding yeast, incorporate temporal (slow and fast) positive feedback loops, or more than one feedback loop that occurs at different times.[7] Having two different temporal positive feedback loops or “dual-time switches” allows for (a) increased regulation: two switches that have independent changeable activation and deactivation times; and (b) linked feedback loops on multiple timescales can filter noise.[7]

Bistability can also arise in a biochemical system only for a particular range of parameter values, where the parameter can often be interpreted as the strength of the feedback. In several typical examples, the system has only one stable fixed point at low values of the parameter. A saddle-node bifurcation gives rise to a pair of new fixed points emerging, one stable and the other unstable, at a critical value of the parameter. The unstable solution can then form another saddle-node bifurcation with the initial stable solution at a higher value of the parameter, leaving only the higher fixed solution. Thus, at values of the parameter between the two critical values, the system has two stable solutions. An example of a dynamical system that demonstrates similar features is

where is the output, and is the parameter, acting as the input.[9]

Bistability can be modified to be more robust and to tolerate significant changes in concentrations of reactants, while still maintaining its "switch-like" character. Feedback on both the activator of a system and inhibitor make the system able to tolerate a wide range of concentrations. An example of this in cell biology is that activated CDK1 (Cyclin Dependent Kinase 1) activates its activator Cdc25 while at the same time inactivating its inactivator, Wee1, thus allowing for progression of a cell into mitosis. Without this double feedback, the system would still be bistable, but would not be able to tolerate such a wide range of concentrations.[10]

Bistability has also been described in the embryonic development of Drosophila melanogaster (the fruit fly). Examples are anterior-posterior [11] and dorso-ventral [12][13] axis formation and eye development.[14]

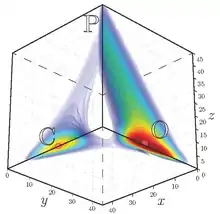

A prime example of bistability in biological systems is that of Sonic hedgehog (Shh), a secreted signaling molecule, which plays a critical role in development. Shh functions in diverse processes in development, including patterning limb bud tissue differentiation. The Shh signaling network behaves as a bistable switch, allowing the cell to abruptly switch states at precise Shh concentrations. gli1 and gli2 transcription is activated by Shh, and their gene products act as transcriptional activators for their own expression and for targets downstream of Shh signaling.[15] Simultaneously, the Shh signaling network is controlled by a negative feedback loop wherein the Gli transcription factors activate the enhanced transcription of a repressor (Ptc). This signaling network illustrates the simultaneous positive and negative feedback loops whose exquisite sensitivity helps create a bistable switch.

Bistability can only arise in biological and chemical systems if three necessary conditions are fulfilled: positive feedback, a mechanism to filter out small stimuli and a mechanism to prevent increase without bound.[6]

Bistable chemical systems have been studied extensively to analyze relaxation kinetics, non-equilibrium thermodynamics, stochastic resonance, as well as climate change.[6] In bistable spatially extended systems the onset of local correlations and propagation of traveling waves have been analyzed.[16][17]

Bistability is often accompanied by hysteresis. On a population level, if many realisations of a bistable system are considered (e.g. many bistable cells (speciation)[18]), one typically observes bimodal distributions. In an ensemble average over the population, the result may simply look like a smooth transition, thus showing the value of single-cell resolution.

A specific type of instability is known as modehopping, which is bi-stability in the frequency space. Here trajectories can shoot between two stable limit cycles, and thus show similar characteristics as normal bi-stability when measured inside a Poincare section.

In mechanical systems

Bistability as applied in the design of mechanical systems is more commonly said to be "over centre"—that is, work is done on the system to move it just past the peak, at which point the mechanism goes "over centre" to its secondary stable position. The result is a toggle-type action- work applied to the system below a threshold sufficient to send it 'over center' results in no change to the mechanism's state.

Springs are a common method of achieving an "over centre" action. A spring attached to a simple two position ratchet-type mechanism can create a button or plunger that is clicked or toggled between two mechanical states. Many ballpoint and rollerball retractable pens employ this type of bistable mechanism.

An even more common example of an over-center device is an ordinary electric wall switch. These switches are often designed to snap firmly into the "on" or "off" position once the toggle handle has been moved a certain distance past the center-point.

A ratchet-and-pawl is an elaboration—a multi-stable "over center" system used to create irreversible motion. The pawl goes over center as it is turned in the forward direction. In this case, "over center" refers to the ratchet being stable and "locked" in a given position until clicked forward again; it has nothing to do with the ratchet being unable to turn in the reverse direction.

See also

- ferroelectric, ferromagnetic, hysteresis, bistable perception

- astable multivibrator, monostable multivibrator.

- Schmitt trigger

- strong Allee effect

- Multistable perception describes the spontaneous or exogenous alternation of different percepts in face of the same physical stimulus.

- Interferometric modulator display, a bistable reflective display technology found in mirasol displays by Qualcomm

References

- Morris, Christopher G. (1992). Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology. Gulf Professional publishing. p. 267. ISBN 978-0122004001.

- Nazarov, Yuli V.; Danon, Jeroen (2013). Advanced Quantum Mechanics: A Practical Guide. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-1139619028.

- Ket Hing Chong; Sandhya Samarasinghe; Don Kulasiri & Jie Zheng (2015). "Computational techniques in mathematical modelling of biological switches". MODSIM2015: 578–584. For detailed techniques of mathematical modelling of bistability, see the tutorial by Chong et al. (2015) http://www.mssanz.org.au/modsim2015/C2/chong.pdf The tutorial provides a simple example illustration of bistability using a synthetic toggle switch proposed in Collins, James J.; Gardner, Timothy S.; Cantor, Charles R. (2000). "Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli". Nature. 403 (6767): 339–42. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..339G. doi:10.1038/35002131. PMID 10659857.. The tutorial also uses the dynamical system software XPPAUT http://www.math.pitt.edu/~bard/xpp/xpp.html to show practically how to see bistability captured by a saddle-node bifurcation diagram and the hysteresis behaviours when the bifurcation parameter is increased or decreased slowly over the tipping points and a protein gets turned 'On' or turned 'Off'.

- Kryven, I.; Röblitz, S.; Schütte, Ch. (2015). "Solution of the chemical master equation by radial basis functions approximation with interface tracking". BMC Systems Biology. 9 (1): 67. doi:10.1186/s12918-015-0210-y. PMC 4599742. PMID 26449665.

- Ghaffarizadeh A, Flann NS, Podgorski GJ (2014). "Multistable switches and their role in cellular differentiation networks". BMC Bioinformatics. 15: S7+. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-15-s7-s7. PMC 4110729. PMID 25078021.

- Wilhelm, T (2009). "The smallest chemical reaction system with bistability". BMC Systems Biology. 3: 90. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-3-90. PMC 2749052. PMID 19737387.

- O. Brandman, J. E. Ferrell Jr., R. Li, T. Meyer, Science 310, 496 (2005)

- Ferrell JE Jr.; Machleder EM (1998). "The biochemical basis of an all-or-none cell fate switch in Xenopus oocytes". Science. 280 (5365): 895–8. Bibcode:1998Sci...280..895F. doi:10.1126/science.280.5365.895. PMID 9572732. S2CID 34863795.

- Angeli, David; Ferrell, JE; Sontag, Eduardo D (2003). "Detection of multistability, bifurcations, and hysteresis in a large calss of biological positive-feedback systems". PNAS. 101 (7): 1822–7. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.1822A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308265100. PMC 357011. PMID 14766974.

- Ferrell JE Jr. (2008). "Feedback regulation of opposing enzymes generates robust, all-or-none bistable responses". Current Biology. 18 (6): R244–R245. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.035. PMC 2832910. PMID 18364225.

- Lopes, Francisco J. P.; Vieira, Fernando M. C.; Holloway, David M.; Bisch, Paulo M.; Spirov, Alexander V.; Ohler, Uwe (26 September 2008). "Spatial Bistability Generates hunchback Expression Sharpness in the Drosophila Embryo". PLOS Computational Biology. 4 (9): e1000184. Bibcode:2008PLSCB...4E0184L. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000184. PMC 2527687. PMID 18818726.

- Wang, Yu-Chiun; Ferguson, Edwin L. (10 March 2005). "Spatial bistability of Dpp–receptor interactions during Drosophila dorsal–ventral patterning". Nature. 434 (7030): 229–234. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..229W. doi:10.1038/nature03318. PMID 15759004.

- Umulis, D. M.; Mihaela Serpe; Michael B. O’Connor; Hans G. Othmer (1 August 2006). "Robust, bistable patterning of the dorsal surface of the Drosophila embryo". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (31): 11613–11618. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10311613U. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510398103. PMC 1544218. PMID 16864795.

- Graham, T. G. W.; Tabei, S. M. A.; Dinner, A. R.; Rebay, I. (22 June 2010). "Modeling bistable cell-fate choices in the Drosophila eye: qualitative and quantitative perspectives". Development. 137 (14): 2265–2278. doi:10.1242/dev.044826. PMC 2889600. PMID 20570936.

- Lai, K., M.J. Robertson, and D.V. Schaffer, The sonic hedgehog signaling system as a bistable genetic switch. Biophys J, 2004. 86(5): p. 2748-57.

- Elf, J.; Ehrenberg, M. (2004). "Spontaneous separation of bi-stable biochemical systems into spatial domains of opposite phases". Systems Biology. 1 (2): 230–236. doi:10.1049/sb:20045021. PMID 17051695. S2CID 17770042.

- Kochanczyk, M.; Jaruszewicz, J.; Lipniacki, T. (July 2013). "Stochastic transitions in a bistable reaction system on the membrane". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 10 (84): 20130151. doi:10.1098/rsif.2013.0151. PMC 3673150. PMID 23635492.

- Nielsen; Dolganov, Nadia A.; Rasmussen, Thomas; Otto, Glen; Miller, Michael C.; Felt, Stephen A.; Torreilles, Stéphanie; Schoolnik, Gary K.; et al. (2010). Isberg, Ralph R. (ed.). "A Bistable Switch and Anatomical Site Control Vibrio cholerae Virulence Gene Expression in the Intestine". PLOS Pathogens. 6 (9): 1. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001102. PMC 2940755. PMID 20862321.