Black Warrior River

The Black Warrior River is a waterway in west-central Alabama in the southeastern United States. The river rises in the extreme southern edges of the Appalachian Highlands and flows 178 miles (286 km) to the Tombigbee River, of which the Black Warrior is the primary tributary.[1] The river is named after the Mississippian paramount chief Tuskaloosa, whose name was Muskogean for 'Black Warrior'. The Black Warrior is impounded along nearly its entire course by a series of locks and dams to form a chain of reservoirs that not only provide a path for an inland waterway, but also yield hydroelectric power, drinking water, and industrial water.[1]

| Black Warrior River | |

|---|---|

The Black Warrior River passes by a park in downtown Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The Hugh R. Thomas Bridge is seen in the background | |

Map of the Black Warrior River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Confluence of the Mulberry and Locust forks |

| • location | Jefferson and Walker counties, Alabama, United States |

| • coordinates | 33°33′25″N 87°11′9″W |

| • elevation | 255 ft (78 m) |

| Mouth | Tombigbee River |

• location | Demopolis, Alabama, United States |

• coordinates | 32°31′55″N 87°51′11″W |

• elevation | 125 ft (38 m) |

| Length | 178 mi (286 km) |

| Basin size | 6,275 sq mi (16,250 km2) |

The river flows through the Black Warrior Basin, a region historically important for the extraction of coal and methane. The cities of Tuscaloosa and Northport grew at the historical head of navigation at the fall line between the Appalachian Highlands (specifically, the Cumberland Plateau) and the Gulf Coastal Plain. Birmingham, though not directly on the river, became a manufacturing hub and one of the largest cities in the South through use of the Black Warrior River in a small part for the transportation of goods. Birmingham actually grew up around a major junction of north-south and east-west railroads, just as Atlanta, Georgia, did.

Overall, the watershed of the Black Warrior has an area of 6,275 square miles (16,250 km2).

Course

The Black Warrior River is formed about 22 mi (40 km) west of Birmingham by the confluence of the Mulberry Fork and the Locust Fork of the Warrior River,[2] which join as arms of Bankhead Lake, a narrow reservoir on the upper river formed by the Bankhead Lock and Dam.[1] Bankhead Lake drains directly into Holt Lake, formed by the Holt Lock and Dam, which itself then drains into Oliver Lake, formed by the Oliver Lock and Dam. These three reservoirs encompass the entire course of the river for its upper 60 miles (80 km) stretching southeast into central Tuscaloosa County and Tuscaloosa, the largest city on the river. Past Oliver Dam, immediately west of downtown Tuscaloosa, the Black Warrior flows generally south in a highly meandering course, joining the Tombigbee River from the northeast at Demopolis. The lower 30 miles (48 km) of the river are part of the long, narrow Lake Demopolis.[1]

The Black Warrior River receives its largest tributary, the North River, from the north about one mile (1.6 km) northeast of Tuscaloosa. North River was dammed in 1968 to form Lake Tuscaloosa, and is the main source for drinking water for the cities, towns, and unincorporated areas of Tuscaloosa County.

Crossings

Outside Tuscaloosa County, only three vehicular crossings of the Black Warrior River exist. Within Tuscaloosa County are seven, though none upstream of the Paul Bryant Bridge in Tuscaloosa.

History

Variant names of the river used over time include Apotaka Hacha River, Bance River, Canebrake or Coinbrake River, Chocta River, Pafallaya River, Patagahatche River, Tascaloosa River, Tuskaloosa River, and Warrior River.[3]

Historically, the river was called the Warrior River above Tuscaloosa and the Black Warrior River below Tuscaloosa. Though unofficial, this naming convention is still often used by the public and occasionally by government agencies. However, the official name of the entire river from Bankhead Lake south is the Black Warrior River.

To develop the coal industries of central Alabama, the US government in the 1880s began building a system of locks and dams that concluded in 17 impoundments. The first 16 locks and dams were constructed of sandstone quarried from the banks of the river and the river bed. Huge blocks of stone were hand shaped with hammer and chisel to construct the locks and dams, and a few of these dams were in service until the 1960s. One example of the craftsmanship of the stone locks is at University Park on Jack Warner Parkway in Tuscaloosa. The bank side wall of Lock 3 (Later renumbered Lock 12 and today largely disassembled) is the last remnant of the old dams made of this dressed stone from the 1880s-90s. A concrete dam completed in 1915, Lock 17 (John H. Bankhead Lock and Dam) is the last and only existing of the original dams, and has been modernized over the years with the addition of spillway gates, and replacement of the two-stage lift with a larger single-lift lock. Lock 17 and Holt Lock and Dam also have hydroelectric power plants owned by the Alabama Power Company supplying electricity for west-central Alabama areas.

This lock and dam system made the Black Warrior River navigable along its entire course and it is one of the longest channelized waterways in the United States forming part of the extended system that link the Gulf of Mexico to Birmingham. Birmingham became the "Pittsburgh of the South", shipping iron and steel products via the Black Warrior River through the Panama Canal to the West Coast of the United States and the world. High-grade coal is barged to Mobile and is then shipped throughout the world, making Mobile the largest coal port in the Southeastern states. Coal mining and production in west-central Alabama is one of the larger employers and is likely to continue being important to the energy needs of the world.

Today, a severe threat to the Black Warrior River is sedimentation, or siltation, the primary causes of which are development projects, logging and mining operations, and the building and maintaining of roads.[4]

Bankhead Lock and Dam, impounding Bankhead Lake in Tuscaloosa County

Bankhead Lock and Dam, impounding Bankhead Lake in Tuscaloosa County Holt Lock and Dam, impounding Holt Lake in Tuscaloosa County

Holt Lock and Dam, impounding Holt Lake in Tuscaloosa County Black Warrior River at Riverwalk Park in Tuscaloosa, Alabama

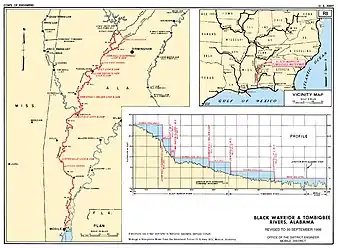

Black Warrior River at Riverwalk Park in Tuscaloosa, Alabama U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Survey of the Black Warrior and Tombigbee Rivers

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Survey of the Black Warrior and Tombigbee Rivers

See also

References

- "Black Warrior | Outdoor Alabama". www.outdooralabama.com. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- "Mulberry Fork | Outdoor Alabama". www.outdooralabama.com. Retrieved 2019-05-28.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Black Warrior River

- "Siltation & Sedimentation". blackwarriorriver.org. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Black Warrior River Black Warrior River

- The Harnessing of the Black Warrior River by Kenneth Willis

- Honoree Fanonne Jeffers. "Tuscaloosa: Riversong" Southern Spaces