Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory

Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory also known as Bromberg DAG AG Factory or DAG Fabrik Bromberg was one of the largest arms factory of Dynamit Nobel during the Third Reich: covering 23 square kilometres (8.9 sq mi), it was the second most extensive DAG factory at the time, after the 35 square kilometres (14 sq mi) Kombinat DAG Alfred Nobel Krzystkowice. Operating from 1939 to 1945 in the south-eastern Bydgoszcz forest, DAG Fabrik Bromberg produced propellants and explosives and realized ammunition handloading.[1]

| Dynamit Nobel AG Factory Bromberg | |

|---|---|

DAG Fabrik Bromberg | |

DAG Fabrik Bromberg | |

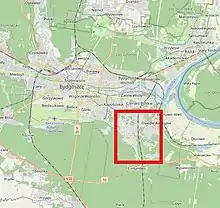

Location of DAG Fabrik in Bydgoszcz | |

| Former names | Alfred Nobel Dynamit Aktien-Gesellschaft in Bromberg |

| General information | |

| Type | Explosive Factory |

| Architectural style | Industrial architecture |

| Address | Ulica Alfreda Nobla, 85-001 Bydgoszcz |

| Town or city | Bydgoszcz |

| Country | Poland |

| Completed | 1939 |

| Owner | City of Bydgoszcz |

| Technical details | |

| Material | brick |

The project included the construction of hundreds of kilometers of roads, railway sidings and thousands of various buildings. After 1945, some of the facilities have been adapted for state chemical enterprises. In 2004, an Industrial and Technological Park was created, covering part of the area, and in 2011, eight building have been converted (approx. 1% of the original factory domain) to comprise the Exploseum, a Museum of Armaments Works from the DAG Fabrik Bromberg together with an open-air museum about German industrial architecture from World War II with an underground tourist route.

Location and structure

The factory ensemble was located and masked in the Bromberg forest, in the south-eastern part of today's Bydgoszcz. The factory area was approximately 23 square kilometres (8.9 sq mi): for communication purposes, tens of kilometers of railway tracks, railway sidings and hundreds of kilometers of concrete slab roads were built. Today, Łęgnowska, Nowotoruńska, Hutnicza, Chemiczna streets and the internal road network of the former Zachem chemical plant run on the ancient DAG factory area. The afforestation and the distance from the city have preserved the facility during and after the war,thus keeping secret the location and the security of the chemical and explosives production activities carried out here.

The plant was divided into two parts, separated by the longitudinal running Upper Silesia-Gdynia coal main, along which the Germans built a second track.[2]

The western part (German: DAG Kaltwasser, Polish: Zimne Wody or cold waters), code name Torf (Peat) was dedicated for the production of gunpowder and its derivatives:

- NC-Betrieb produced nitrocellulose;

- POL-Betrieb for smokeless powder. Shooting and artillery tests could be realized on a ballistic test site, where each batch of manufactured explosives was assessed;

- NGL-Betrieb produced nitroglycerin, which, once mixed with nitrocellulose then dryed gave powder dough.

.jpg.webp)

The Eastern part (German: DAG Brahnau, Polish: Łęgnowo), code name Kohle (Coal) was intended for the production of blasting explosives to be incorporated into missiles, mines and bombs:

- TRI-Betrieb, production of nitro compounds and TNT;

- DI-B-Betrieb, production of dinitrobenzene, used in particular for missile propulsion (e.g. V1). A small firing range for blasting explosives was available on site;

- Füllstelle, ammunition handloading, including aerial bombs, artillery shells, land mines, sapper charges and small caliber ammunition;

- an unfinished area of the plant, manufacturing sulfuric acid was located on the south-eastern edge of the domain.

The two main areas (Kaltwasser and Brahnau) were linked by one road, which ran on a viaduct over the coal main railroad near the station of Bydgoszcz-Żółwin, disused today. Three departments had the largest footprint in the area: POL-Betrieb, DI-B Betrieb and TRI-Betrieb.

Staff was accommodated in housing estates built on purpose, in the northern sector (near today's Kliniczna street) for engineers and in the eastern part for management staff. The latter has survived till this day, in Świetlicowa street (Awaryjne district). A barrack camp for forced workers had been also erected, in the vicinity of current Szpitalna and Hutnicza streets.[3]

The southern portion of the DAG factory network was situated on a vast inland dune field. Such terrain had a beneficial effect on the set-up of factory buildings: small valleys separating sandy ridges ensured the isolation of the edifices, even in case of an accidental explosion. In addition, the dense pine forest provided an efficient masking.[4] Nowadays, this region comprises the Protected Landscape Area of Toruń-Bydgoszcz Basin Dunes which has been under protection since 1991.

History

The DAG Bromberg factory was established between 1939–1944 to support the expansion of the Nazi Germany war machine. The secret plant producing explosive and assembling ammunition, built by forced labor work, belonged to the Dynamit Aktiengesellschaft (DAG) (Dynamit Corporation), based in Troisdorf, Germany, nearby Bonn. DAG's roots go back to the 1860s: it has been established by Alfred Nobel, inventor of dynamite and smokeless powder, founder as well of the Nobel Prize.

Creation and growth of DAG

The history of the DAG company began in 1863, when Alfred Nobel developed a method of producing nitroglycerin on an industrial scale. In 1864, Nobel built the first factory in Vinterviken near Stockholm, and in 1865, it began its expansion into the European market. This year, the first dynamite plant was built in German Empire. By 1875, 14 factories were set up in 12 countries. In 1876, the company was transformed into a joint-stock company, which eventually took the name of Dynamit-Actien Gesellschaft vormals Alfred Nobel & Co. Hamburg (abbreviated as DAG). When Alfred Nobel passed away in 1896, DAG counted 93 factories worldwide.

After Nazis accessed power in 1933, an intense arm production happened, which, from 1935, took the form of a particularly significant expansion of bombing industry. Thus, most of the explosive and gunpowder of the Nazi war machine have been produced by DAG and Westfälisch-Anhaltische Sprengstoff-Actien-Gesellschaft (or WASAG) and their subsidiaries, such as DAG-Verwertchemie and WASAG-Deutsche Sprengchemie.

In 1939–1945, Third Reich numbered a total of 80 explosive factories (32 of which belonged to DAG-Verwertchemie), 27 warfare factories and 241 ammunition production plants. While until 1939, most of the facilities were located only west of Oder river, after the outbreak of the war, plants expanded also east of Oder. In 1944, DAG produced a quarter of the total production of military assets of the Third Reich, with its most productive facilities in Allendorf near Marburg, Hessisch Lichtenau, Krümmel and Clausthal-Zellerfeld. The largest in terms of acreage were the factories in Bydgoszcz[5] and in Krzystkowice near Nowogród Bobrzański. On current Polish territory, one can also mentioned the remains of a Deutsche Sprengchemie, which comprised 2500 employees, in Zasieki.

All necessary investments were carried out with the highest confidentiality, allowing the factories to be referred to by the locals as producing chocolate, praline, cake or textile.

Construction of the Bromberg DAG factories

The Wehrmacht Supreme Military Command had issued, as early as September 1939, a staff order intending to identify places in the Polish annexed territories where to build gunpowder and explosives factories. Three areas were pre-selected: Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poznań and Bydgoszcz. The latter was picked up as having excellent masking conditions in the forest, being close to Vistula river and to railway lines (coal main line Silesia-Gdynia, railway Berlin-Kaliningrad). The work began soon after the occupation of Bydgoszcz by the German army in September 1939, in the forest near Łęgnowo suburb, with measuring and preparatory works. In November 1939, a 35-km long fence was installed, covering roughly a forest area of 25 square kilometres (9.7 sq mi). The size of the planned project required two DAG construction offices to be established: Bauleitung I (western part) and Bauleitung II (eastern part).[6] Construction and assembly works started in full swing in 1940, and two years later the first explosives and ammunition were produced. By the end of 1944, the industrial estate encompassed 1500 buildings, 360 km of roads and 40 km of railway tracks. A newly erected railway station (Bydgoszcz Emilianowo) played a pivotal role in the production sustainement process.

The comprehensive construction program included production, warehouse and workshop buildings, bunkers, laboratories, Fire Brigade facilities, outpatient clinics, administrative and social buildings, guardhouses, surveillance edifices, housing estates (for executives) and barracks camps (for forced laborers). The project incorporated underground and overhead utilities. Underground networks consisted of:[4]

- industrial waterworks;

- drinking water supply (25 wells dwelved);

- three separate sewage networks (acid, post-production and neutral);

- high and low voltage cabling;

- telephone and emergency signaling systems.

Surface pipelines were dedicated for:

- steam distribution;

- condensate and hot water;

- compressed air;

- concentrated mineral acids and hydrocarbons chemically treated.

As far as energy supply was concerned, two combined heat and power plants and two boiler houses were constructed in 1940. Boiler rooms were to supply the lines of denitration and nitric acid concentration with high-pressure steam and also to heat the production buildings.[1] The largest plant (EC III) was equipped with 3 turbine sets. These units were fueled by coal, delivered using a ramp and unloaded via a system of winches; they operated continuously until January 1945.[7]

The spatial organisation of the plant resulted from efforts to minimize the consequences of explosion. Each stage of the production process was taking place in separate, usually small, buildings and the movements between them were realized by means of surface (roads) and underground (tunnels) systems. The buildings were located at different heights from one another and openings were never lined up. This arrangement prevented chain reactions and possible destruction of technological lines in the event of a disruption at any of the prodution stages. In addition, lines were duplicated so as to increase the likelihood of keeping production up in the occurrence breakdowns. Staff could use multi-branches escape tunnels equipped with bunkers. For safety goals, plants were scattered over a large area and masked by earth embankment.

Camouflage was enhanced by planting trees on roofs, painting facilities khaki (including roads and railways) and by using forest roads as communication lines. In spring 1944, a wooden, night-lit mock-up factory was even erected, located 2 to 3 km south of the real plant, in order to confuse allied pilots during air raids. As a matter of fact, only one raid took place on July 23, 1944, without causing major damage.

In order to reduce the effects of a possible explosion, two types of buildings were built: light edifices (mainly warehouses) and bunkers. Light buildings were made of bricks and surrounded by earth embankments: in case of an explosion, the entire blast was directed upwards. On the other hand, bunker-type buildings, used when explosion risk was assessed as high, consisted of quadrilateral edifices with three walls and a thick reinforced concrete ceiling. In this case, the architectural concept directed the blast to the fourth side, i.e. an exhaust wall made of wood and glass, the debris being blocked by the earth embankment located behind. Such reinforced buildings could withstand the burst of the shock wave and not fall apart.[1]

As for the protection and safety of the project, additional efforts were deployed, such as:

- sectorizing factory network accesses to identified employees;

- detailed plant regulations;

- badges;

- personal searches to prevent cigarettes, matches and metal objects;

- fences and gates guarded day and night.

Plant security, employee control and fire service were supervised by the company guards (German: Werkschutz). Their responsibilities included as well banning any contacts between Germans and foreign workers. Eventually, some incidents occurred, especially on May 21, 1943, at the bomb filling station and on January 12, 1944, in the NGL zone.

In 1941, 75% of the production buildings and networks necessary for the plant's operation had been completed. Between 1942 and 1944, a water and sewage system entered into service and the last buildings were constructed. In 1943, a test shooting range for rockets was established in the newly created training area of Kabat, near Solec Kujawski.[8] In 1942, a project was raised to build a reloading station along the Brda river, with a cableway supplying coal, as well as a sewage installation discharging into the Vistula river. These plans, however, were never carried out for financial reasons.

Products

The main product and specialty of DAG Bromberg was smokeless powder (POL), an improved version of ballistite. Nitrocellulose (NC), nitroglycerin (NGL), TNT (TRI) and dinitrobenzene (DI-B) were also manufactured. In the handloading (German: füllstelle) section, metal casings were filled with explosives. The final products were ready-to-use weapons, like aerial bombs, artillery shells or powder charges.

Plant production began in 1941, with the position of director taken over by Adolf Kämpf (1879-1957), an experienced chemist, graduate from the Technical University Stuttgart[5] and the facility integrated on November 1, to the DAG-Verwertchemie complex. In 1942, the first smokeless powder production line was completed and in 1943, dinitrobenzene and TNT lines together with denitration and bomb filling factories established. In the same year, a first line for nitrocellulose was partly set up as well as half of the nitroglycerin department; one power plant and one engine room were put into operation. In February 1944, Wehrmacht High Command commissioned an extension of the existing lines and the construction of new manufactoring capacities for blasting explosives and rocket powders:

- dinitrobenzene;

- TNT;

- RDX;

- NGu;

- powder fittings for missile weapons;

- synthesis of concentrated sulfuric acid.

In October 1944, the threat of Soviet seizing of the complex ground to a halt some of these projects (expansion of TNT, dinitrobenzene and gunpowder zones). It was only in 1944 that the DAG Bromberg reached almost complete autonomy, importing only raw materials (i.e. acids, cellulose, glycerol and other additives) eventhough it was aimed at having the plant entirely self-sufficient by building a sulfuric acid production line, which was never realized.[1]

In 1942, the complex produced 1200 t of gunpowder, 7300 t in 1943 and 13700 t in 1944. Nitrocellulose production started in 1943 (2000 t) to reach 7500 t the following year. In January 1944, nitroglycerin manufacture began in the NGL zone while TNT production zone was established only in January 1945. Although there is no precise data on weapon handloading, it was a strategically important activity: in particular, shells for machine guns were produced in Bydgoszcz metallurgical plants, such as the former Fiebrandt railway signal factory at 32 Grunwaldzka Street. In addition, 250 kilograms (550 lb) and 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) air bombs, mortar and nebelwerfer ammunitions were conveniently tested on the nearby training ground of Kabat.[4] In 1944, the gunpowder produced at POL-Betrieb was also tested on missiles code name Rheinbote in the experimental area, located between Szubin and Łabiszyn.[4]

According to estimates, the production of the DAG Bromberg factory complex amounted for 5% of the Wehrmacht demand for gunpowder and explosives. It is assessed that a 1944 daily production of powder dough from the NGL line was enough to satisfy the manufacture of the following assets:[1]

- 20 million rifle ammunition;

- 26,000 artillery ammunition (75–88 mm caliber) or 9,000 large caliber artillery ammunition.

Workforce

On December 1, 1942, about 10000 people were working in the DAG Bromberg factory. This number jumped to 20000 at the end of the war, encompassing workers, forced laborers and prisoners of war. During the operation of the complex (1939-1945), between 40000 and 50000 POW died at work.

Initially, local labor was employed, then German direction used non-residents and POWs. Among this workforce, over 50% were Poles, others were, by decreasing numbers: Germans (mainly skilled workers coming from the homeland), Russians or Ukrainians (approx. 3000), Czechs, Italians, Yugoslavs, French and English. They were mostly POWs, as well as members of German paramilitary youth organizations, such as Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD). On July 15, 1944, more than 1000 Jewish women from the Stutthof concentration camp were sent to the plant to work on ammunition handloading and at Bydgoszcz East railway station.[4]

To accommodate non-local workers, 18 camps were built, consisting of around 100 wooden and 150 brick barracks (at present day Wojska Polskiego avenue, Hutnicza street and in the Glinki district). In one barrack unit lived about 100 people, 200 if it was a POW barrack. In the vicinity of this camps, 29 large anti-aircraft bunker units were constructed, each one could accommodate from 300 to 500 people. On March 16, 1943, a penal camp (German: Arbeitserziehungslager) and a Reich Labour Service camp were also set up on the factory premises. In the end of 1944, these camps were hosting 5200 people.

Underground activity of the Polish resistance movement

In 1940, a local underground army group (ZWZ or Polish: Związek Walki Zbrojnej) was established at DAG Bromberg, led by Henryk Szymonowicz (aka Marek). Between March and May, 250 people were recruited, allowing to start a cooperation with a group of French and English prisoners. A map of the complex was elaborated by a brigade of Polish electricians (Leszek Jakub Biały, Bronisław Zdzisław Bruski, Zdzisław Henryk Nędzyński) and forwarded to AK headquarters, together with a number of secret documents.[6]

Sabotage also played an important role in the activities of the resistance movement. The most elaborate sabotage action (the largest in Pomerania) was called Operation Krem: carried out on March 23, 1944, it caused an explosion that killed German engineers working on the development of the factory.

Another resistance movement, Darzbór, had been operating from the Zagroda facility located in the forest area of Emilianowo. This group was subordinated to ZWZ (1939-1942), then to the AK (1942-1945). After WWII, it kept its fight against communism under the umbrella of the organisation Freedom and Independence (Polish: Wolność i Niezawisłość) (1945-1948). Darzbór was dealing with the intelligence within the DAG Bromberg complex, helping POWs, sabotaging Bydgoszcz Emilianowo railway station, hiding and transferring RAF officers and running guerrilla activities.[9]

Luftmunitionanstalt 1/11 Bromberg

In addition to the DAG Bromberg site, an aviation ammunition plant (Luftmunitionanstalt 1/11 Bromberg) had been operating in Osowa Góra, on the western outskirts of Bydgoszcz. This factory, established in 1917, had been taken over in 1939 by the Luftwaffe. A few years later, an extension was constructed, with production criteria similar to those in force at DAG Bromberg. The densely wooden conditions allowed perfect masking conditions to these important military facilities.

Communication means was provided by the railway line No. 18 (Bydgoszcz-Piła), to which branch lines with loading ramps were added. The manufacture complex numbered about 100 different buildings, including concrete bunkers and POW camp barracks employed on production lines. In 1941, the Luftmunitionanstalt 1/11 Bromberg employed 1200 people.

The plant was performing handloading for air bombs, manufacturing electrical ballast and fuzes. In a remote and secret part, expanded in 1943- 1944, were developped unprecedented missiles, inflated with compressed air, which blast radius neared 2 kilometres (1.2 mi). These facilities were blown up by retreating German troops in January 1945.[4]

Soviet period after WWII

The factory activity continued until the very last days before the arrival the Soviet and Polish troops. The director himself, Adolf Kämpf, left the plant with the last staff and fled to DAG Malchow in Mecklenburg, according to the devised evacuation plan.[6]

On January 22, 1945, it was decided to stop the production and evacuate German personnel. Technical devices were not smashed but the technical documentation was carried away out of the city with the retreating Germans. Bydgoszcz and the DAG factory complex were seized 2 days later, on January 24–26, by the 2nd Belorussian Front.

After WWII, at the behest of the Soviet War Trophy Commission, all technical equipments were gradually dismantled and transported to USSR by the Red Army. Between 1300 and 1500 railtrucks were necessary to ship the whole DAG equipment, probably to Ukraine: the freight included massive components, such as the CHP plants or the boiler houses. Once stripped of its equipment, the premises were handed over to the Polish authorities on August 31, 1945. Administered by the Central Management of Arms industry in Warsaw, the complex was now watched by the Internal Security Corps or KBW for Korpus Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego.

In 1945, the State Gunpowder Factory was set up in Łęgnowo. In 1948, chemical plants no. 9 and 11 were also established: in the 1950s they were transformed into the Bydgoszcz Zachem Chemical Plant (Polish: Zakłady Chemiczne Zachem w Bydgoszczy). The Zachem plant used part of the existing infrastructure for civilian production, but also carried out secret manufacturing of explosive for the armies of the Warsaw Pact. The increasing demand of production for chemical plants no. 9 and 11 necessitated in 1954 the launch of a combined heat and power plant using the framework of the one previously stripped of equipment by the Soviet soldiers. A plaque commemorating this opening is still visible on the tiles of the ancient engine room.[7]

Most of the German post-industrial buildings had been abandoned since the end of the war, only some were used as production workshop and warehouses. However, in 1952, an accidental detonation on the premises of the plant destroyed a section of a former German production line. The entire premises was kept fenced and inaccessible to outsiders. All in all, the legacy of the DAG Bromberg complex within the Zachem factory was permanent and surrounding. The new Polish premises encompassed:[10]

- 475 buildings from the different production departments (NGL-Betrieb, NC-Betrieb, POL-Betrieb, TRI / DI-B Betrieb, Fülstelle);

- 360 kilometres (220 mi) of concrete or granite roads;

- 40 kilometres (25 mi) of railway tracks with four reloading stations;

- boiler houses feeding 50 megawatt-hours (180 GJ) power plants;

- an industrial water collector to the Vistula River;

- 25 deep drinking water wells.

From 1956 to 1980, several trials were carried out to use the ex-DAG buildings for other chemical productions, but most of them did not turn out successful:[10] while explosives manufacturing was still viable, production lines for nitroglycerin and gunpowder were not used at all. In the 1970s, 150 ha of the ancient POL-Betrieb area were converted to set up a plant for chemical synthesis of plastics. Some of the ex-German buildings not re-used were crushed with explosives and the rubble was removed and tossed into the marshy bed of the Brda river estuary to the Vistula. Over the years, several hundred buildings were overgrown with forest.[10]

Post-soviet Period

For many years, hundreds of buildings, connected by tunnels and masked in Bydgoszcz forest area, were explored in secret by lovers of technology and military history. For long, the entire area of the former factory was surrounded by an aura of mystery.

After 1989, Zachem plant was divided into two independent companies:

- Nitrochem in the eastern part, working on explosives production. It was a certified supplier of the Defense industry. Today Nitrochem is one of the largest TNT producer in Europe and the main TNT supplier for the American ammunition firm ATK;

- Zachem Bydgoszcz in the western part.

On December 30, 2013, Zachem management board filed a bankruptcy petition, confirmed by the court on March the following year. The premises comprised 120 kilometres (75 mi) of roads on area of 30 ha. Sold in parts, the city of Bydgoszcz bought in 2015, 9 km of streets and 19 ha of the domain.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Ten years earlier (2004) , municipal authorities had already established an Industrial and Technological Park on one of Zachem's abandoned plot. The expansion of this park dictated, inter alia, several demolitions of ex-DAG Bromberg buildings. The growing interest for the history of the site, combined with the risk of complete liquidation of the remains of the ancient factory led to the creation in 2005 of two conservation zones:

- POL-Betrieb, with gunpowder production lines located in the central part of the complex;

- NGL-Betrieb with nitroglycerin production lines in the southern part.

In autumn 2007, the NGL-Betrieb area was taken over by the Regional Museum in Bydgoszcz, aiming to organize a museum and tourist facility in the place. The project, co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (5 million PLN), was implemented in 2008–2011. This museum, called Exploseum uses eight renovated buildings from the NGL-Betrieb. The Exploseum showcases an open-air museum of industrial architecture combined with the Museum of Armaments Factory DAG Fabrik in Bydgoszcz. Visitors can walk a route leading through tunnels connecting the different buildings. On the post-factory premises, multimedia and interactive exhibitions expose the history of the DAG complex, the place of the factory in the city and display military armaments and explosives. In addition, various exhibitions explain the abuse of forced labor, the resistance movements with conspiracies and sabotage actions at the time in occupied Bydgoszcz.

In 2018, despite the protest of local conservation associations, several buildings of the POL-Betrieb in a state of threatening ruin were torn down.[12] The preserved piece of the POL-Betrieb department displays a compact but complete gunpowder production line, consisting of 18 buildings standing in a circle, so as to optimize the production process. All types of machinery and tools used in the process are exhibited: rolling mills, extruders, crushers, mixers, transformer stations and warehouses. During the war, five of these buildings housed colossal powder squeezers nicknamed Mamuth, which processed the gunpowder produced in the NGL zone: the powder dough was produced here, then rolled, folded and re-rolled many times to ensure an even combustion when fired.[13] While larger WWII plants still exist in Poland (like the DAG Alfred Nobel complex in Krzystkowice or in Zasieki) only the remains of the DAG Bromberg factory allow partial and safe access to sightseeing for walkers, tourists or curious people.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to DAG Fabrik Bromberg. |

References

- Lachamjer, Jerzy (2007). Technologia nitrogliceryny w zakładach Dynamit Nobel A.G. w Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska XXVIII. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 383–408.

- Weckwerth, Marek (15 January 2010). "Wyprawa do DAG Fabrik". pomorska.pl. Gazeta Pomorska. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Kulesza, Maciej (2 May 2020). "Czy miasto wyburzy historyczne budynki D.A.G. Fabrik Bromberg na Kapuściskach?". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Wyborcza Bydgoszcz. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- Woźny, Jacek (2007). Archeologia bliskiej przeszłości w kontekście niemieckiej architektury militarnej regionu bydgoskiego. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 12. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy. pp. 81–95.

- Pszczółkowski, Michał (2009). Adolf Kampf-dyrektor zakładów DAG Werk Bromberg. Kronika Bydgoska XXXI. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 435–446.

- "History". exploseum.pl. muzeum.bydgoszcz. 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Kulesza, Maciej (12 October 2016). "Zobacz jak wygląda opuszczona elektrociepłownia w Bydgoszczy". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Wyborcza Bydgoszcz. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- Maciej Kulesza, WM (30 August 2018). "Tajemnica wieży na poligonie niedaleko Bydgoszczy. Co tam testowali Niemcy?". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Wyborcza Bydgoszcz. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Szefke, Agnieszka Wiktoria. Leśnictwo Emilianowo k. Bydgoszczy na tle dziejów konspiracji pomorskiej w latach 1939–1948. Bydgoszcz: Instytucie Historii i Stosunków Międzynarodowych Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego w Bydgoszczy. pp. 1–132.

- Gruszka, Zbigniew (2011). "Zakłady Nobla w Bydgoszczy 1939-1945 r." ioh.pl. inne oblicza historii. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Czajkowska, Małgorzata (21 December 2015). "Bydgoszcz kupuje dziewięć kilometrów ulic na terenie Zachemu". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Wyborcza. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Kulesza, Maciej (23 March 2018). "Bydgoski krąg walcarek z II wojny światowej ma zostać zburzony". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Wyborcza. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Lewińska, Aleksandra (26 January 2017). "Unikalny obiekt zagrożony. Społecznicy rozpoczynają walkę". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Wyborcza. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

External links

- Exploseum

- Nitrochem site

- (in Polish) Article about D.A.G. fabrik Bromberg tokens

- (in Polish) Article about DAG fabrik Bromberg

Bibliography

- (in Polish) Youtube film - remaining buildings on the ex-Dynamit Nobel AG Factory site

- (in Polish) Youtube film by UKW stydents on Exploseum site

- (in Polish) The Nobel Factory in Bydgoszcz 1939-1945

- (in Polish) Lachamjer, Jerzy (2007). Technologia nitrogliceryny w zakładach Dynamit Nobel A.G. w Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska XXVIII. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 383–408.

- (in Polish) Pszczółkowski, Michał (2009). Adolf Kampf-dyrektor zakładów DAG Werk Bromberg. Kronika Bydgoska XXXI. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 435–446.

- (in Polish) Woźny, Jacek (2007). Archeologia bliskiej przeszłości w kontekście niemieckiej architektury militarnej regionu bydgoskiego. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 12. Bydgoszcz: Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy. pp. 81–95.