Bryant & May

Bryant & May was a British company created in the mid-19th century specifically to make matches. Their original Bryant & May Factory was located in Bow, London. They later opened other match factories in the United Kingdom and Australia, such as the Bryant & May Factory, Melbourne, and owned match factories in other parts of the world.

Formed in 1843 by two Quakers, William Bryant and Francis May, Bryant & May survived as an independent company for over seventy years, but went through a series of mergers with other match companies and later with consumer products companies; and were taken over.

The registered trade name Bryant & May still exists and it is owned by Swedish Match, as are many of the other registered trade names of the other, formerly independent, companies within the Bryant & May group.

Formation

The match-making company Bryant & May was formed in 1843 by two Quakers, William Bryant and Francis May, to trade in general merchandise. In 1850 the company entered into a relationship with the Swedish match maker Johan Edvard Lundström in order to capture part of the market of the 250 million matches that used in Britain each day. Their first order was for 10 or 15 cases of 720,000 matches (each case held 50 gross boxes, with a box holding 100 matches). The next order was for 50 cases; and later orders for 500 cases. This partnership was successful, so Francis May and William Bryant decided to merge the partnership with Bryant's company, Bryant and James, which was based in Plymouth.[1] The company began production after purchasing the rights in Britain for £100.[2][3][lower-alpha 1] In line with their religious beliefs, Bryant and May decided to produce only safety matches, rather than lucifers.[5] In 1850 the company sold 231,000 boxes; by 1855 this had risen to 10.8 million boxes and to 27.9 million boxes in 1860.[3] Market preference in the UK was for the familiar lucifer match, and by 1880 Bryant & May were also producing them.[2] The same year the company began exporting their goods; in 1884 they became a publicly-listed company. Dividends of 22.5 per cent in 1885 and 20 per cent in 1886 and 1887 were paid.[6]

In 1861 Bryant relocated the business to a three-acre site, on Fairfield Road, Bow, East London. The building, an old candle factory, was demolished and a model factory was built in the mock-Venetian style popular at the time. The factory was heavily mechanised and included twenty-five steam engines to power the machinery. On nearby Bow Common, the company built a lumber mill to make splints from imported Canadian pine.[7][8] Bryant & May were aware of phossy jaw. If a worker complained of having toothache, they were told to have the teeth removed immediately or be sacked.[9]

In the 1880s Bryant & May employed nearly 5,000 people, most of them female and Irish, or of Irish descent;[8] by 1895 the figure was 2,000 people of which between 1,200 and 1,500 were women and girls.[10] The workers were paid different rates for completing a ten-hour day, depending on the type of work undertaken.[11] The frame-fillers were paid 1 shilling per 100 frames completed; the cutters received 23⁄4 d for three gross of boxes, and the packers got 1s 9d per 100 boxes wrapped up. Those under 14 years-of-age received a weekly wage of about 4 s.[12] Most workers were lucky if they took the full amounts home, as a series of fines were levied by the foremen, with the money deducted directly from wages. The fines included 3 d for having an untidy workbench, talking or having dirty feet—many of the workers were bare-footed as shoes were too expensive; 5 d was deducted for being late; and a shilling for having a burnt match on the workbench. The women and girls involved in boxing up the matches, they had to pay the boys who brought them the frames from the drying ovens, and had to supply their own glue and brushes. One girl who dropped a tray of matches was fined 6 d.[13][14]

The match boxes were made through domestic outwork under a sweating system.[lower-alpha 2] Such a system was preferred because the workers were not covered under the Factory Acts. Such workers received 21⁄4 to 21⁄2 d per gross of boxes. The workers had to provide glue and string from their own funds.[16][17]

In 1861, at the Fairfield Works, a dilapidated site that had once been used for the manufacture of candles, crinoline and rope, close to the River Lea in Bow, they began to manufacture their own safety matches and "other chemical lights". This site was gradually expanded as a model factory. The public were initially unwilling to buy the more expensive safety matches so they also made the more profitable traditional Lucifer Matches.[18]

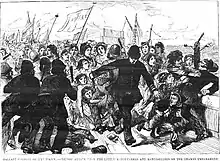

In 1871 Robert Lowe, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, attempted to introduce a tax of 1⁄2 d per hundred matches.[5][19] The Times, in a leader on the proposal, opined that the tax was "a singularly reactionary proposal" that would affect the poor more heavily.[19] Match-making companies complained about the new levy and arranged a mass-meeting at Victoria Park, London on Sunday 23 April; 3,000 match workers attended, the majority of whom were from Bryant & May. It was resolved to march on the following day to the Houses of Parliament to present a petition. Several thousand match-makers set off from Bow Road in an orderly fashion.[20][21]

The demonstration comprised mostly girls between the ages of thirteen and twenty,[22] and were described in The Times as "beyond doubt of the working classes. They ... were accompanied by men and women of their own class, without any admixture of the usual agitators."[23] The marchers were harassed along the way before their progress was blocked by police at Mile End Road.[21] Much of the march progressed through the police line, but parts were split off and made their way via alternative routes to the Westminster, by which time the march numbered approximately 10,000.[22] Clashes ensued, and The Time described that the police had "by their hard usage of the matchmakers and spectators, converted what was before not an ill-behaved gathering into a resisting, howling mob".[23] The Manchester Guardian described that "policemen, strong in their sense of officialism, and bullying in their strength, approached the verge of brutality".[22]

On the same day as the meeting in Victoria Park, Queen Victoria wrote to the prime minister, William Gladstone, to protest about the tax:

it is difficult not to feel considerable doubt as to the wisdom of the proposed tax on matches ... [which] will be felt by all classes to whom matches have become a necessity of life. ... this tax which is intended should press on all equally will in fact only be severely felt by the poor which would be very wrong and most impolitic at the present moment.[24]

The day following the march, Lowe announced in the House of Commons that the proposed tax was being withdrawn.[25]

Bryant and May was involved in three of the most divisive industrial episodes of the 19th century, the sweating of domestic out-workers, the wage "fines" that led to the London matchgirls strike of 1888 and the scandal of "phossy-jaw". The strike won important improvements in working conditions and pay for the mostly female workforce working with the dangerous white phosphorus.[18]

Mergers with other match makers

To protect its position Bryant & May merged with or took over its rivals. These were:

- Bell and Black

In 1885 - factories in Stratford, Manchester, York and Glasgow.[18]

- Diamond Match

In 1901 the American match maker the Diamond Match Company bought an existing match factory in the United Kingdom, at Litherland, near Liverpool, and installed a continuous match making machine that could produce 600,000 matches per hour. Their matches were sold under the Captain Webb, Puck and Swan Vesta brand names. Bryant & May could not compete, so in 1905 they bought the assets and goodwill of the British Diamond Match Company; and the (American) Diamond Match Company acquired 54.5 percent of the share capital of Bryant & May.

- S. J. Moreland and Sons

In 1913 Bryant & May also took over the Gloucester match maker S.J. Moreland and Sons, who made and sold matches under the trade name England's Glory.

- Swedish Match

In 1927 Bryant & May combined with J. John Masters & Co. Ltd (match importers and owners of the Abbey Match Works, Barking, Essex) and the Swedish Match Company's interests in the British Empire (except for major plant in India and elsewhere in Asia) to become the British Match Corporation.[26]

- Albright and Wilson

In 1929, the British Match Corporation set up a jointly-owned company with another Quaker company Albright and Wilson: The A & W Match Phosphorus Company. It took over that part of Albright and Wilson's Oldbury site which was manufacturing amorphous phosphorus and phosphorus sesquisulfide, as these two chemicals were used in safety matches and strike-anywhere matches, respectively.[27]

Merger with Wilkinson Sword

In 1973 the British Match Corporation merged with Wilkinson Sword to form the new company Wilkinson Match.

Wilkinson Match's shares were acquired by US company Allegheny International from 1978 with Allegheny taking full ownership in 1980. In 1987 Allegheny filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and Swedish Match re-acquired the company. In 1990 Swedish Match sold the Wilkinson Sword business, retaining the match business.[28]

Closure

In 1971 the Northern Ireland factory, Maguire & Patterson closed down following a terrorist attack. The original Bow match factory was closed in 1979, when it still employed 275 people; unlike some of the other match factories little recent investment had taken place. The Bow factory site consisted of a number of listed buildings, which have subsequently been converted into the Bow Quarter flats complex.[29]

In the 1980s, factories in Gloucester and Glasgow closed too leaving Liverpool as the last match factory in the UK. This continued until December 1994.[30] The premises survive today as 'the Matchworks' (grade 2 listed building) and the Matchbox all using the existing buildings with renovations done by Urban Splash.

The former Australian match factory, in Melbourne, closed in the mid-1980s. This was converted into offices in 1989.[31]

The British match brands continue to survive as brands of Swedish Match and are made outside the UK. Other parts of the merged company involved in shaving products survive, and still use the trade name Wilkinson Sword in Europe, and the Schick trade name elsewhere. However, the shaving products are made in Germany.

Products

Vitafruit

Vitafruit was a confectionery manufactured by the Bryant & May group in 1988. There were three varieties including tropical fruit flavour (Vitafruit), mint (Vitamint) and a throat soother (Vitasooth).

When Swedish Match acquired Bryant & May the confectionery arm of the business was sold and eventually the new owners stopped production of Vitafruit.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- £100 in 1850 equates to approximately £10,772 in 2021 pounds, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[4]

- The Fifth Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Sweating System defined "sweating" as "the evils known by that name are ...:

- A rate of wages inadequate to the necessities of the workers or disproportionate to the work done.

- Excessive hours of labour.

- The insanitary state of the houses in which the work is carried out."[15]

References

- Beaver 1985, p. 25.

- Emsley 2000, pp. 80–81.

- Arnold 2004, p. 5.

- Clark 2019.

- Arnold 2004, p. 6.

- Satre 1982, p. 11.

- Emsley 2000, p. 83.

- Arnold 2004, p. 7.

- Raw 2011, p. 93.

- Satre 1982, p. 12.

- Arnold 2004, p. 9.

- Beaver 1985, p. 39.

- Emsley 2000, pp. 92–93.

- Beer 1983, p. 32.

- House of Lords Report on the Sweating System. 1890.

- Emsley 2000, pp. 88–89.

- Satre 1982, p. 10.

- Arnold 2004.

- "Leader". The Times.

- Beaver 1985, p. 48.

- Raw 2011, p. 144.

- "The Matchmakers' Demonstration". The Guardian.

- "The Government and the Matchmakers". The Times.

- Beaver 1985, p. 47.

- Beaver 1985, p. 51.

- "J. John Masters". The National Archives. Richmond, Surrey. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Threfall (1951).

- Competition Commission Reports 1987: Bryant & May and Wilkinson Sword

- Building, 11 June 1993

- The Times, 23 December 1994.

- Sunday Age, 3 December 1995.

Books

- Beaver, Patrick (1985). The Match Makers: The Story of Bryant & May. London: Henry Melland. ISBN 978-0-907929-11-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beer, Reg (1983). The Match Girls Strike, 1888. London: The Labour Museum. OCLC 16612310.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Emsley, John (2000). The Shocking History of Phosphorus: A Biography of the Devil's Element. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-76638-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raw, Louise (2011). Striking a Light: The Bryant and May Matchwomen and their Place in History. London: Continuum International. ISBN 978-1-4411-1426-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Official reports

- Fifth Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Sweating System (Report). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1890. OCLC 976630092.

News articles

- "The Government and the Matchmakers". The Times. 25 April 1871. p. 10.

- "Leader". The Times. 21 April 1871. p. 9.

- "The Matchmakers' Demonstration". The Guardian. 26 April 1871. p. 6. -->

Journals

Internet and audio visual media

- Arnold, A. J. (2004). "'Ex luce lucellum'? Innovation, class interests and economic returns in the nineteenth century match trade" (PDF). University of Exeter. ISSN 1473-2904. Retrieved 30 May 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Gregory (2019). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 28 January 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)