Bug (engineering)

In engineering, a bug is a defect in the design, manufacture or operation of machinery, circuitry, electronics, hardware, or software that produces undesired results or impedes operation. It is contrasted with a glitch which may only be transient. Sometimes what might be seen as unintended or defective operation can be seen as an feature.

History

The Middle English word bugge is the basis for the terms "bugbear" and "bugaboo" as terms used for a monster.[1]

The term "bug" to describe defects has been a part of engineering jargon since the 1870s and predates electronic computers and computer software; it may have originally been used in hardware engineering to describe mechanical malfunctions. For instance, Thomas Edison wrote the following words in a letter to an associate in 1878:

It has been just so in all of my inventions. The first step is an intuition, and comes with a burst, then difficulties arise—this thing gives out and [it is] then that "Bugs"—as such little faults and difficulties are called—show themselves and months of intense watching, study and labor are requisite before commercial success or failure is certainly reached.[2]

In a comic strip printed in a 1924 telephone industry journal, a naive character hears that a man has a job as a "bug hunter" and gives a gift of a backscratcher. The man replies "don't you know that a 'bug hunter' is just a nickname for a repairman?"[3]

Baffle Ball, the first mechanical pinball game, was advertised as being "free of bugs" in 1931.[4] Problems with military gear during World War II were referred to as bugs (or glitches).[5] In the 1940 film, Flight Command, a defect in a piece of direction-finding gear is called a "bug". In a book published in 1942, Louise Dickinson Rich, speaking of a powered ice cutting machine, said, "Ice sawing was suspended until the creator could be brought in to take the bugs out of his darling."[6]

Isaac Asimov used the term "bug" to relate to issues with a robot in his short story "Catch That Rabbit", published in 1944.

The term "bug" was used in an account by computer pioneer Grace Hopper, who publicized the cause of a malfunction in an early electromechanical computer.[7] A typical version of the story is:

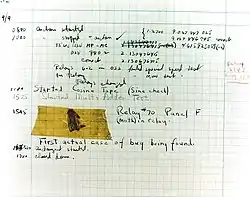

In 1946, when Hopper was released from active duty, she joined the Harvard Faculty at the Computation Laboratory where she continued her work on the Mark II and Mark III. Operators traced an error in the Mark II to a moth trapped in a relay, coining the term bug. This bug was carefully removed and taped to the log book. Stemming from the first bug, today we call errors or glitches in a program a bug.[8]

Hopper did not find the bug, as she readily acknowledged. The date in the log book was September 9, 1947.[9][10][11] The operators who found it, including William "Bill" Burke, later of the Naval Weapons Laboratory, Dahlgren, Virginia,[12] were familiar with the engineering term and amusedly kept the insect with the notation "First actual case of bug being found." Hopper loved to recount the story.[13] This log book, complete with attached moth, is part of the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.[10]

The related term "debug" also appears to predate its usage in computing: the Oxford English Dictionary's etymology of the word contains an attestation from 1945, in the context of aircraft engines.[14]

"It's not a bug, it's a feature"

Some user bugs work as the designer intended, reflecting a mismatch between the specifications and user expectations. Sometimes the behavior in question is written in user documentation or is billed as an undocumented feature, which is captured by the catchphrase "It's not a bug, it's a feature" (INABIAF).[15] This quip is recorded in The Jargon File dating to 1975 and may predate that.

See also

References

- Computerworld staff (September 3, 2011). "Moth in the machine: Debugging the origins of 'bug'". Computerworld. Archived from the original on August 25, 2015.

- Edison to Puskas, 13 November 1878, Edison papers, Edison National Laboratory, U.S. National Park Service, West Orange, N.J., cited in Hughes, Thomas Parke (1989). American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870-1970. Penguin Books. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-14-009741-2.

- Cy Meyn, Hattie the Hello Girl, The Mountain States Monitor Vol. XIX, No. 1 (Jan, 1924), Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Co.; page 34, bottom.

- "Baffle Ball". Internet Pinball Database.

(See image of advertisement in reference entry)

- "Modern Aircraft Carriers are Result of 20 Years of Smart Experimentation". Life. June 29, 1942. p. 25. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- Dickinson Rich, Louise (1942), We Took to the Woods, JB Lippincott Co, p. 93, LCCN 42024308, OCLC 405243, archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- FCAT NRT Test, Harcourt, March 18, 2008

- "Danis, Sharron Ann: "Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper"". ei.cs.vt.edu. February 16, 1997. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- "Bug Archived March 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine", The Jargon File, ver. 4.4.7. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- "Log Book With Computer Bug Archived March 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine", National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- "The First "Computer Bug", Naval Historical Center. But note the Harvard Mark II computer was not complete until the summer of 1947.

- IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol 22 Issue 1, 2000

- James S. Huggins. "First Computer Bug". Jamesshuggins.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society. 49, 183/2, 1945 "It ranged ... through the stage of type test and flight test and 'debugging' ..."

- Nicholas Carr. "'IT'S NOT A BUG, IT'S A FEATURE.' TRITE—OR JUST RIGHT?". Wired.