Caguax

Caguax was a Taíno cacique who lived on the island of Borikén (Taíno name for Puerto Rico) before and during the Spanish colonization of the Americas. His yucayeque or Taino village's name was Turabo, it included the lands in the Caguas Valley and surrounding mountains.[1] This area included the modern municipalities of Caguas, Aguas Buenas, Gurabo, and portions of San Lorenzo, Juncos and Las Piedras in east-central Puerto Rico.[2] Guaybanex Caguax was an early convert to the Catholic faith adopting the Spanish name Francisco at the time of his baptism. His high rank in Taino society allowed him to retain his Taino name: Gaybanex along with his surname: Caguax. [3] Francisco Guaybanex Caguax sought to avoid conflict with the Spanish, as a powerful chief in the northern slopes and plains of the island he understood the heavy toll his people would suffer if they oppose the Spanish rule. Seeking peaceful ways to deal with the situation. As early as 1508 Caguax cooperated with the colonists request for labor and food supply. In 1511 he was one of only two chiefs accepting the peace offered by the Spanish just a few months after the Taino Revolt started. Caguax was taken captive to Hacienda del Toa in 1512. There he was humiliated before his nitainos as he was forced to be the governor's personal servant. Caguax died in captivity in 1518 or early 1519. He was succeeded by his daughter Maria Bagaaname.[4]

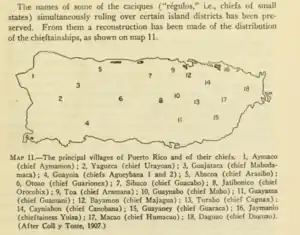

Late in 1508 Juan Ponce de León, commissioned by Nicolás de Ovando to colonize the island of San Juan Bautista, arrived in the territory of cacique Agüeybaná I in southwest Puerto Rico. There, both leaders performed the Guaytiao ceremony in which they exchanged names as a promise not to hurt each other. This sort of peace treaty allowed Ponce de León to settle the island and receive cooperation from Agüeybaná I's cacique allies to grow the yuca needed to feed the Spanish settlers.[5]

Caguax was among those allies willing to use his authority to organize his nitainos or "captains", as the Spanish called them, to direct the labor of naborias under them for such endeavor.[6] Products such as yuca and peppers were grown in Caguax's domain for colonists Francisco Robledo and Juan de Castellanos. In 1510 this production had a value of 255 gold pesos. Robledo and Castellanos not only had rights over the production but also over the Indians that would provide the labor in the fields or conucos in Taino language. [7] When gold was discovered in the Turabo River the same Taino power structure was again used to force them to work the mines and rivers in search of gold.[2]

By 1511 the growing tensions between the Spanish and the Taino exploded in revolts around the island that lasted into 1518. After Ponce de León won the first battles early in 1511 peace was offered to the island caciques. Only two accepted: Caguax and Otoao.[8] During this time of great distress Ponce de León was replaced, as the island governor, by Juan Cerón and Nicolás de Ovando was replaced in Santo Domingo by Diego Colón. Up until this time Caguax, his family, nitainos and naborias lived in their own yucayeque in the Caguas Valley near the Caguitas River. Archaeologist Carlos A. Pérez Merced, excavating in the area, found ceramic and pottery from three different indigenous periods: Igneri, pre-Taino and Taino. This indicates the existence of an ancient indigenous settlement at the site.

Early in 1512 Cerón redistributed Ponce de León's caciques among his friends and banished Caguax his relatives and entourage to Hacienda del Toa in the northern coastal plain, west of Caparra, the first Spanish settlement on the island. His mother, siblings, wives and children have been identified using early records sent to la Real Hacienda to account for the distribution of clothes and other goods, call the "cacona", given to the Indians in captivity once a year between 1513-1519.[9] [10] Historians Raquel Rosario Rivera and Jalil Sued Badillo among others state Cacica Yayo is Caguax mother, therefore she is the ranking cacica through which Turabo chiefs would be born. Her daughter Catalina, Caguax's sister, should have born the next cacique or cacica to reign after Caguax. but at the time of her death in captivity no heirs were alive as it was also the case of her sister Maria. Their brother: Juan Comerio could not inherit the line of succession. Cacica Catalina died soon after being taken to el Toa. Caguax death came later between the end of 1518 and the beginning of 1519. With no line of succession María Bagaaname, Caguax's eldest daughter,[11][12] was ceded the right to bear the successor. Comerio and Isabel Taya were Caguax's two other children. It is unclear which of his three children were from either of his two wives: María or Leonor. Around 1524 Maria Bagaaname married Diego Muriel an overseer in Hacienda del Toa's. This marriage was approved by the authorities and bore descendants.[13] As for the nitainos forced to move with Caguax to oversee the work in Hacienda del Toa records show Aguayayex, Guayex, Caguas, Juanico Comerio, Juan Acayaguana, Diego Barrionuevo, Esteban directing agricultural tasks and Pedro in charge of the mines. They directed 230 naborias from Caguax's yukayeque taken there to work the conucos and the mines.[14] Cerón forced Caguax to be his personal servant as his nitainos and naborias were forced to work the conucos and gold mines.[2]

The city and municipality of Caguas, Puerto Rico derives its name from him. A neighborhood there is named after him.[15]

See also

- List of Puerto Ricans

- List of Tainos

References

- "Dictionary of the Taino Language". taino-tribe.org (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Rosario Rivera, Raquel. Primeros pobladores de Caguas (in Spanish). Departamento de Desarrollo Cultural, Municipio Autonomo de Caguas.

- Sued Badillo, Jalil. La mujer indigena y su sociedad. San Juan, Editorial Cultural, 2002.

- Raquel Rosario Rivera. Primeras familias pobladoras de Caguas. Departamento de Desarrollo Cultural, Municipio Autónomo de Caguas, 2005

- Vicente Murga Sanz, Historia Documental de Puerto Rico, Volumen II (1519-1520) (Rio Piedras: Editorial Plus Ultra, 1956)

- Francisco Moscoso, Agricultura y sociedad en Puerto Rico, siglos 16 al 18:un acercamiento desde la historia. (San Juan: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña y Colegio de Agrónomos de Puerto Rico, 1999)

- Raquel Rosario Rivera. Primeras familias pobladoras de Caguas. Departamento de Desarrollo Cultural, Municipio Autónomo de Caguas, 2005

- Ricardo E. Alegría. Descubrimiento, conquista y colonización de Puerto Rico, 1493-1599 (San Juan: Colección de Estudios Puertorriqueños, 1969)

- Vicente Murga Sanz, Historia Documental de Puerto Rico, Volumen II, 1519-1520 Rio Piedras: Editorial Plus Ultra, 1956.

- Tadoni, Aurelio:Documentos de la real Hacienda de Puerto Rico, Vol I, Rio Piedras: Centro de Investigaciones Historicas de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, 1971

- Raquel Rosario Rivera. Primeras familias... pag.67

- Moscoso, Francisco: Caguas en la conquista española, Siglo 16. Caguas: Gobierno Municipal de Caguas, 1998

- Sued Badillo, Jalil La mujer indigena y su sociedad. San Juan, Editorial Cultural, 2002

- Raquel Rosario Rivera. Primeras familias pobladoras de Caguas. Departamento de Desarrollo Cultural, Municipio Autónomo de Caguas, 2005

- "Bulletin : Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of American Ethnology". Internet Archive. 23 October 1901. p. 540. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2019.