Cairngorm Plateau disaster

The Cairngorm Plateau disaster (also known as the Feith Buidhe disaster) occurred in November 1971 when six fifteen-year-old Edinburgh school students and their two leaders were on a navigational expedition in a remote area of the Scottish mountains. When the weather deteriorated they adopted their emergency plan and headed for the Curran shelter, but they failed to reach it and became stranded for two nights on the high plateau in a blizzard. Five children and the leader's assistant died of exposure. A sixth student and the group's leader survived the ordeal with severe hypothermia and frostbite. The tragedy is regarded as Britain's worst mountaineering accident.

A fatal accident inquiry led to formal requirements being placed on leaders for school expeditions. After acrimony in political, mountaineering, and police circles, the Curran shelter was demolished in 1975.

Cairngorms

Topography

.jpg.webp)

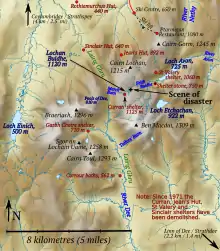

The Cairngorms are a mountainous region of Scotland, named after the 1,245-metre (4,085 ft) Cairn Gorm mountain which overlooks Aviemore, the main town in the area. The central region is an area of high granite plateau at about 1,200 metres (3,900 ft), deeply dissected by long glacial valleys running roughly north–south. There are mountain peaks on the individual plateaux between the valleys but these are the eroded stumps of once much higher mountains – they are not much higher now than the plateaux themselves.[1] Between two of these valleys, the Lairig Ghru and the Lairig an Laoigh, extends the Cairngorm Plateau[note 1] of granite boulders and gravel where Cairn Gorm itself and the 1,309-metre (4,295 ft) Ben Macdui – the highest mountain in the Cairngorms and the second highest in the British Isles – are the main summits. The edges of the plateaux are in places steep cliffs of granite and they are excellent for skiing, rock climbing and ice climbing.

Weather conditions

.jpg.webp)

Their height, distances and their severe and changeable weather make the Cairngorms the most arduous area in the United Kingdom.[2] Snow can fall at any time during the year and snow patches persist all summer – for snow and ice climbing the area is the most dependable in Britain.[3][4]

The plateau area has a subarctic climate and only supports sparse tundra vegetation.[5] The shattered terrain is more like the high ground in the arctic regions of Canada or Norway than the European Alps or North American Rocky Mountains.[6] The weather often deteriorates rapidly with elevation, so that when there are moderate conditions 150 metres below the plateau the top can be stormy or misty and there can be icy or powdery snow. Even when no snow is falling the wind can whip up lying snow to produce white-out conditions for a few metres above the surface and snowdrifts can build up rapidly in sheltered places. Gravel can be blown through the air and walking can be impossible.[7][8] Adam Watson says,

"When a gale is accompanied by thick storms of ground drift, or worse, by heavy falling blizzards plus ground drift, or worse still by mist as well, conditions can be extremely serious on the plateau, making it suffocating and difficult to breathe, hard to open your eyes, impossible to see anything beyond your own feet, and unable to communicate with your party except one at a time by cupping an ear and shouting into it".[9]

In January 1993 a wind speed of 176 miles per hour (283 km/h) was measured at Cairngorm summit weather station – the greatest wind speed ever recorded over land in the UK.[note 2][10][11]

Trails and buildings in the Cairngorms

The valleys between the individual plateaux were used as drove roads by cattle drovers who built rough protective shelters for their arduous journeys. Even today there are no paved roads over the Speyside–Deeside watershed and the passes are impossible even for four-wheel drives. The Lairig Ghru pass between Speyside and Deeside is about 19 miles (30 km) long and reaches its greatest height at Pools of Dee at 810 metres (2,660 ft) where the water may be frozen over even in midsummer.[12][13] This route has a total ascent of about 670 metres (2,200 ft) between habitation at Coylumbridge in Speyside and Linn of Dee.[12] At about the same time that droving was dying out towards the end of the 19th century, deer stalking estates were flourishing and so the shelters were developed into bothies to provide improved, though still primitive, accommodation for gamekeepers.[8] In modern times these bothies have been taken over by the Mountain Bothies Association for use by trekkers and climbers to provide shelter and rough sleeping accommodation.[8]

.jpg.webp)

Starting in 1960 an area in the rugged Northern Corries between Aviemore and Cairn Gorm was developed for alpine skiing. A road was constructed to an elevation of 650 metres (2,130 ft) in Coire Cas where a ski centre was built and ski lifts and tows were installed, one going up to a new restaurant, the Ptarmigan, at 1,080 metres (3,540 ft). In good weather it was an easy walk from there to the Cairngorm Plateau.[14][note 3]

After the Second World War, the Scottish Council for Physical Recreation established Glenmore Lodge beside Loch Morlich and on the road between Aviemore and the ski centre. In 1959 this moved to a purpose-built centre nearby (later the Scottish Centre for Outdoor Training, which provides training for leadership in mountaineering), and staff were on the spot to help in mountaineering emergencies.[15][16]

In the 1960s a military group erected, without permission from the local authorities, the St Valery, El Alamein and Curran shelters on the Cairngorm Plateau.[17][note 4] Greg Strange states the Curran shelter was built at the request of the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Association.[20] There seems to be agreement that HMS Caledonia apprentices demolished Curran and St Valery in 1975.[21][22]</ref> These could often become buried in snowdrifts but they attracted hikers and campers.[17][23][24] The Curran shelter was of metal covered with boulders, had a floor area 4 by 2 metres (12 by 7 ft), and was beside Lochan Buidhe, the highest standing water in Britain.[25][26] [27] Predicting it would attract inexperienced walkers, the Mountain Rescue Committee of Scotland and Adam Watson wrote to the Nature Conservancy pointing out the danger of a shelter in this location, but nothing was done about the matter.[28]

Mountain rescue

At the time, mountain rescue in the central Cairngorms was the responsibility of the Scottish North-East Counties Constabulary.[29] The mountain rescue teams consisted entirely of unpaid civilian volunteers co-ordinated by the Mountain Rescue Committee of Scotland, with the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team (MRT) being the first to be called on for assistance on the Cairngorm Plateau.[30] They, in turn, could request helicopter support from RAF Kinloss. The Braemar MRT and Kinloss RAF MRT[note 5] would also attend if there was a major incident or if the location for the rescue was uncertain.[31][32]

School expedition

Expedition leadership

In November 1971 a fourteen-strong party of students from Ainslie Park School in Edinburgh was staying with three leaders at Edinburgh Council's Lagganlia outdoor training centre in Kincraig.[33] In overall charge was 23-year-old Ben Beattie, the school's instructor in outdoor education with the Mountain Instructor Certificate, who had quite extensive mountaineering experience although his experience in the Cairngorms in winter was very limited. Also on the expedition was Beattie's girlfriend, 21-year-old Catherine Davidson, who was a final-year student at Dunfermline College of Physical Education and who was approved by the school to help run the mountaineering club. She had less overall mountaineering experience but she had twice been in the Cairngorms in winter. Accompanying them was Shelagh Sunderland, aged eighteen, who had just started as a Lagganlia volunteer trainee instructor and had no experience in the Cairngorms.[34][35]

Start of the expedition

On Saturday 20 November the party set off on a two-day navigational exercise to cross the Cairngorm Plateau from Cairn Gorm south to Ben Macdui. Because they were very late in starting (it was almost 11:00 when they left Lagganlia) they used the Cairngorm ski lift to get close to the plateau and then, as planned, they separated into two groups – the more experienced group led by Beattie set off and was followed by the group led by Davidson and Sunderland. After crossing the plateau both groups were to descend to the Corrour Bothy at a much lower level in the Lairig Ghru where they would spend the night – sunset was just before 16:00. The less-experienced group of 15-year-olds would then return along the Lairig Ghru while the other group would return by traversing Cairn Toul and Braeriach on the far side of the valley. In case of emergency each group was to go to the Curran shelter high on the plateau. This plan had been approved in advance by the head of Lagganlia, John Paisley, who could forbid unsuitable expeditions.[36][37][38]

Shortly after the groups set off the weather deteriorated, as had been forecast to the groups' knowledge, but the first party, led by Beattie, successfully navigated to the Curran shelter where they dug snow from the door and spent the night. The leader of the second party, worried that they would not be able to find the shelter in white-out conditions – she knew it could become completely covered in snow – decided on a forced bivouac out on the plateau. The site she chose was at a slight dip at the head of the Feith Buidhe burn about 460 metres (500 yd) east of Lochan Buidhe and the Curran shelter. Beattie was not worried about the missing people because he assumed they had gone to some other shelter.[36][37][38][35]

Davidson's group

On Saturday afternoon Davidson had abandoned the original plan when the conditions became poor and some of the children became distressed. Instead of navigating directly to the Curran shelter she had headed slightly downhill aiming for the Feith Buidhe stream hoping to follow it up to Lochan Buidhe and so reach the shelter beside the lochan (small loch). The burn was completely obliterated by snow so she gave up hope of finding Curran and prepared to bivouac in what, unknown to her, was a major accumulation area for snow.[39] John Duff, leader of the Braemar MRT, later considered this was a serious mistake: "to attempt a winter bivouac, in a storm, on a Cairngorms plateau, is literally a life or death decision, and a last option".[40] He also wrote that the major mistake was even to have considered "an appallingly over-ambitious expedition for teenage children" and he laid the blame on all the people making and accepting the plans.[26]

They sheltered in sleeping bags and bivouac sacs in the lee of a snow wall they built and to begin with they kept up good spirits.[41] However, as the snow became deeper through the night there was panic because of the fear of being buried or suffocated. With daylight on Sunday, a boy could be heard shouting under the surface and Sunderland was barely conscious. Davidson and the other boy set off to get help but only got a few yards before they were forced back. Throughout the day the blizzard raged and after dark they could see the flares of a search party but their shouts were not heard and they had lost their own flares in the snow. During this night the children were becoming delirious and were dying. On Monday morning Davidson set off by herself to try to get rescue.[42]

Beattie's group on Sunday

The previous day, on the Sunday, Beattie's group had great difficulty getting out of the hut because of the deep snow and in arduous conditions they were scarcely able to descend from the plateau. After dark at 16:30 they reached Rothiemurchus Hut where they were able to telephone Lagganlia and they met their transport vehicle at 17:30. The children were returned to Lagganlia while Beattie and Paisley drove to the ski centre where they were unable to learn any news. They then went to Glenmore Lodge and then Aviemore police station where at 19:00 they reported Davidson's party missing. Three pairs of rescuers were immediately dispatched from Glenmore Lodge into the blizzard and the night and the Cairngorm, RAF Kinloss, Braemar and Aberdeen MRTs were called out. The mountain rescue teams made their preparations so they could start off hours before first light on Monday.[43]

Rescue attempts

In stormy but moderating conditions on Monday, 22 November 1971, fifty men were searching with helicopter support. In the morning the Braemar MRT, travelling from the south, reached Corrour Bothy only to find it unoccupied. It was at about 10:30 that Davidson was spotted from a helicopter.[44] The Whirlwind helicopter had been dispatched from RAF Leuchars in Fife and the pilot attempted to fly up the line of Glen Shee but turbulence meant he had to reduce airspeed to 70 knots (130 km/h; 81 mph) with groundspeed less than walking pace. At Pools of Dee he was reduced to a hover and was unable to ascend to the plateau so he took a wide detour to Glenmore Lodge from where the crew was asked to make an airborne check of various shelters, without any delay for refuelling. At Curran shelter there was nothing to be seen but as they turned to go back to Glenmore Lodge they spotted what they thought was a red tent.[44][45]

Edging closer and without reference points in the whiteout they realised they had got very close to a person on her hands and knees – Davidson was still up on the plateau trying to crawl for help. 64 metres (70 yd) away, the closest they could manage, two crew were unloaded but after they had reached the casualty they could not carry her to the helicopter because her legs were locked in a kneeling position. The helicopter could get no closer because when it applied power the blowing snow obliterated vision so one of the crew jumped out to lead it in the right direction using the winch wire. There was no sign of anyone else from Davidson's group. Davidson was taken by helicopter to Aviemore where she was met by ambulance. She was in the advanced stages of hypothermia and her hands were frozen solid but, although she was confused and barely able to speak, she managed to let her rescuers know that the rest of the party was close to where she had been rescued.[45][note 6]

By this time the cloud base had become lower and no helicopter could get near but several search teams on foot, with Beattie and Paisley included, converged on the location of the catastrophic bivouac through snow sometimes waist deep. The bodies of six children and the assistant were dug out, one from a depth of 1.2 metres (4 ft). All were dead except the last person to be uncovered, Raymond Leslie, who was still breathing so he was cared for by a doctor from the Braemar MRT on his first serious call-out.[45] At 15:00 a Royal Navy Sea King helicopter arrived, guided by the leader of the RAF Kinloss MRT walking ahead firing flares, and Leslie, the surviving boy, was airlifted to Raigmore Hospital where he and Davidson eventually recovered.[45][47] Some of the instructors from Glenmore Lodge had been out for twenty hours so in the darkness the dead had to be left on the mountain to be brought down the next day.[33][44]

Aftermath

.jpg.webp)

The disaster has often been described as Britain's worst mountaineering tragedy.[48][49] A memorial service to the victims was held at Insh parish church on 28 November 1971.[50][note 7] The Secretary of State for Scotland was asked about the Cairngorms Disaster in parliament and there was a suggestion that all local authorities should follow the lead recently set by Edinburgh Education Authority and ban school expeditions from mountaineering in winter.[52]

At the fatal accident inquiry held in Banff in February 1972, Adam Watson was the chief expert witness for the Crown.[53][54] It emerged that the consent form issued to parents did not say that winter mountaineering was involved. Also, only one of the parents had been told the outing was going to be to the Cairngorms.[55] The inquiry reported that the deaths had been due to cold and exposure. It recommended

- there should be special regard for fitness and training,

- parents should be given fuller information about outdoor activities,

- parties should be led by fully qualified instructors and accompanied by certified teachers,

- suitable locations for summer and winter expeditions should be identified in consultation with mountaineering organisations,

- experts should advise on whether high-level shelters should be removed,

- the mountain rescue teams were praised and consideration should be given to supporting the teams financially and generally,

- following any future disaster there should be closer liaison between authorities and parents.

The jury did not want to discourage future adventurous outdoor activities. The advocate for the parents suggested that the overall leader of the expedition and the principal of Lagganlia should be found at fault but the inquiry did not make any finding of fault.[55]

The recommendation concerning the possible removal of high-level shelters was to become a cause of major disagreement. Traditional "bothies" were built for stalkers and gamekeepers and were in the valleys. The shelters being questioned were modern ones built high up on the plateau. The argument to keep them was that any shelter in an emergency was better than none – Cairngorm MRT, Banffshire County Council and local estate owners were of this opinion. However the Braemar MRT, most mountaineering bodies, the Chief Constable of police and Adam Watson thought they should be removed. More and more experts and politicians became involved and in July 1973 the Secretary of State for Scotland launched a formal consultation. Eventually, the Scottish Office decided it had no powers in the matter. In February 1974 at a meeting which excluded everyone except the local authority, police, and mountaineering experts, a decision for removal was taken and after further argument they were indeed removed.[10][56][57]

The tragedy had a major effect on mountaineering in Britain, particularly concerning adventure expeditions for children. At a political level, urged on by the press, there were proposals to ban mountaineering courses for children or at least require formal certification for their leaders. Compulsory insurance for mountaineers also came on the agenda. The British Mountaineering Council, representing practising amateur mountaineers and their clubs was initially opposed to all this – a bureaucracy should not be supervising adventure. On the other hand, the Mountain Leader Training Board, composed of educators, was in favour on grounds of safety and teaching environmental awareness. Eventually a compromise was reached with the two bodies combining and a Mountain Leadership Certificate becoming required for educational expeditions.[58][59][60]

Interviewed in 2011, the father of one of the girls who died said he had thought the trip was simply to the Lagganlia centre and he had no idea that they were going to be climbing the mountains. On the Sunday night a policeman had come to the door to say they would be late home – even in Edinburgh there was strong wind and deep snow. Later in the night a newspaper reporter arrived and said the whole party was missing. It was only on Monday afternoon when the parents were gathered at the school that the news came that five children were dead. The father explained that the boy who survived was the smallest child in the party – maybe the others (two women leaders, four girls and one boy) had been huddling round him to protect him from the cold.[61] In 2015 someone who had been a pupil at the school in 1971 wrote "The school was in mourning for some time after that and I don't think that Mr Chalmers, the headmaster, ever really recovered."[62][63]

Ben Beattie was appointed to a job at Glenmore Lodge but in 1978 he was killed climbing Nanda Devi in Garhwal Himalaya.[64][65] Catherine Davidson completed her course and then emigrated to Canada in 1978.[51][66] Raymond Leslie became a top-class canoeist who went on to represent Britain.[66] Edinburgh Council still runs Lagganlia.[67]

Notes

- "Cairngorm Plateau" is the name of this specific plateau. To its west is the Moine Mhor – Great Moss – with the greatest number of Munros.

- The Cairngorm weather station is at 1,245 metres (4,085 ft) and has been operating since 1977

- The walk could be dangerous because it was apparently so easy and the presence of large numbers of people was also causing environmental damage. When the ski lift was replaced with a funicular railway in 2001 people ascending on the railway were no longer permitted to go out onto the plateau.

- Allen & Davidson, Baker, Duff and Watson give varying accounts of how and why these shelters came to be built. It is generally agreed that they were built in the 1960s by a group from a single military establishment and that El Alamein and St Valery had plaques bearing the insignia the 51st Highland Division who fought in these battles in WW II. However, Ray Sefton, one time leader of the RAF Kinloss MRT,[18] is reported (in a blog by David Whalley, another one-time leader of KMRT[19]) as saying that they were built in memory of the 51st Highland Division by apprentices from HMS Caledonia, an onshore base in Rosyth Dockyard, led by CSM Jim Curran of the Royal Marines. The shelters were to support cross-country skiing which was at the time seen to be appropriate for the Cairngorm plateau.<ref name='FOOTNOTEAllenDavidson2012Chapter Six, p. 3/21'>Allen & Davidson (2012), Chapter Six, p. 3/21.

- RAF Kinloss, as well as giving helicopter support, also operated an RAF mountain rescue team.

- She was only able to say the words "Burn – lochan – buried" but this gave sufficient clue.[46]

- The school pupils who died were Carol Bertram, Susan Byrne, Lorraine Dick, Diane Dudgeon and William Kerr. The boy who survived was Raymond Leslie.[51]

References

Citations

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Prologue: The Mountains, p. 1/14.

- Bonington, Chris (2012). Introduction to Cairngorm John. in Allen & Davidson 2012

- Watson (1992), p. 16.

- English, Charlie (7 February 2009). "Doctor Watson's feeling for snow". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Prologue: The Mountains, p. 3/14.

- Watson (1992), p. 18.

- Watson (1992), pp. 19–21.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Prologue: The Mountains, p. 10/14.

- Watson (1992), p. 21.

- Baker (2014), "The Lost Shelter", pp. 41–59.

- Crowder, J G; MacPherson, W N. "Cairngorm Automatic Weather Station Homepage". cairngormweather.eps.hw.ac.uk. Heriot-Watt University. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- Watson (1992), pp. 94–95.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Prologue: The Mountains, p. 4/14, Chapter Four, p. 9/17.

- Watson (1992), pp. 71–72.

- Hopkins, David; Putnam, Roger (2012). Personal Growth Thru Adventure. Routledge. pp. 47–48. ISBN 9781134082902. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016.

- Watson (1992), p. 58.

- Watson (2012), p. 86.

- MacDonald, Tom. "RAF Mountain Rescue & associated memorabilia". Pinterest. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Robertson, John (15 December 2014). "Former RAF Group Captain saddened by loss of proud legacy". Press and Journal. Aberdeen Journals Ltd. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Strange (2010), p. 172.

- Whalley, David (29 April 2014). "El Alamein bothy in the Cairngorms". heavywhalley. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Whalley, David (18 July 2012). "RAF Kinloss MRT – The swinging 70's". heavywhalley. Archived from the original on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Chapter Six, p. 3/21.

- Hewitt, Dave (8 August 2002). "Summit Talks: Cairn Taggart". Scotland Online Outdoors. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012.

- Dorwood, Joe. "Curran Shelter". The Upland of Mar. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016.

- Duff (2001), p. 104.

- Stott (1987), p. 69.

- Duff (2001), p. 83.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Three Reasons for writing this book, p. 2/3, Chapter Six, p. 5/21.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Three Reasons for writing this book, p. 3/3.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Chapter Six, p. 5/21.

- Duff (2001), p. 33.

- "Journey to death mountain Thirty years ago six children left for an adventure weekend in the Cairngorms. Only one came back". The Herald. Glasgow. 27 October 2001. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016.

- Duff (2001), p. 98.

- Strange (2010), p. 226.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Prologue: The Mountains, pp. 11–14/14, Chapter Six, pp. 1–2/21.

- Duff (2001), pp. 98–107, Chapter 11, Death of the Innocents.

- Watson (1992), p. 25.

- Duff (2001), pp. 103–106.

- Duff (2001), p. 106.

- Strange (2010), pp. 227-228.

- Duff (2001), pp. 106–107.

- Duff (2001), pp. 101–108.

- Duff (2001), pp. 108–117.

- Campbell, Bill. "Cairngorm Disaster 1971". Scottish Saltire Aircrew Association. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- Strange (2010), p. 228.

- "Blizzard claims six in mountain tragedy". Strathspey and Badenoch Herald. 6 June 2007. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- Duff (2001), p. 107.

- Allen & Davidson (2012), Prologue, p. 13/14.

- "Tributes paid to Cairngorm victims". Glasgow Herald. 29 December 1971. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "The day mountains claimed their worst toll". The Herald. Glasgow: Herald and Times Group. 25 November 1996. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "Cairngorms (Climbing Accident)". Hansard. HC Deb 23 November 1971 vol 826 cc1136-41. 23 November 1971. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- Duff (2001), p. 115.

- "Media Release: Top Scottish honours for 'Mr Cairngorms', Dr Adam Watson". Fort William Mountain Festival. allmediascotland.com. 9 February 2012. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016.

- Macdonald, George (16 February 1972). "Jury's Findings on Cairngorm Disaster". Glasgow Herald.

- "Bothies may not be Demolished". Glasgow Herald. 27 June 1974. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- Duff (2001), pp. 115–125.

- Porter, John; Venables, Stephen (2014). "Chapter 16: Don't Get Me Wrong". One Day as a Tiger: Alex MacIntyre and the birth of light and fast Alpinism. Vertebrate Publishing. ISBN 9781910240090.

- Loynes, Chris; Higgins, Peter (1997). "Safety and Risk in Outdoor Education" (PDF). In Higgins, Peter; Loynes, Chris; Crowther, Neville (eds.). A Guide for Outdoor Educators in Scotland. Adventure Education & Scottish Natural Heritage. pp. 26–29. ISBN 1-874637-04-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2016.

- Fyffe, Allen. "Mountain Leader Award – Background". Mountaineering Council of Scotland. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016.

- Dick, Sandra (25 November 2011). "Forty years after Diane Dudgeon died on a frozen hillside, her father reveals the pain of not know what really happened". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- Donaldson, Keith (15 December 2015). "Ainslie Park Secondary School: Cairngorm Disaster". EdinPhoto. Peter Stubbs. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016.

- "Death on the Hills". The Free Library. Farlex, Inc. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016. excerpted from Ralston, Gary (2001). "Death on the Hills; Rescue leader's grief 30 years after tragedy on Glengorm that claimed six children". Scottish Daily Record.

- Perrin, Jim (11 August 2000). "Fred Harper". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016.

- Hallen, Cynthia (20 September 2004). "Nanda Devi Summit Log (#5814)". World Mountain Encyclopedia. Peakware. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016.

- Strange (2010), p. 229.

- "About Us". Lagganlia Centre for Outdoor Learning. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016.

Works cited

- Allen, John; Davidson, Robert (2012). Cairngorm John: A Life in Mountain Rescue (eBook). Dingwall: Sandstone Press. ISBN 978-1-908737-48-9. John Allen joined the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team after the time of the disaster and went on to become its leader.

- Baker, Patrick (2014). "The Lost Shelter". The Cairngorms: A Secret History. Birlinn. ISBN 9780857908094.

- Duff, John (2001). A Bobbie on Ben Macdhui: Life and Death on the Braes o' Mar. Huntly: Leopard Magazine Publishing. ISBN 0953453413. John Duff was leader of the Braemar Mountain Rescue Team at the time of the disaster.

- Stott, Louis (1987). The Waterfalls of Scotland. Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 0-08-032424-X.

- Strange, Greg (2010). The Cairngorms: 100 years of Mountaineeiing. Scottish Mountaineering Trust.

- Watson, Adam (1992). The Cairngorms, Lochnagar and the Mounth (6th ed.). Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 0-907521-39-8. Adam Watson is an academic and hill walker with very great experience of the Cairngorms.

- Watson, Adam (2012). Human Impacts on the Northern Cairngorms. Paragon Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908341-77-8.