Canon Alexander Galloway

Canon Alexander Galloway (c. 1478 – c. 1552) was a 16th-century cleric from Aberdeen in Scotland. He was not only a Canon of St Machar’s Cathedral, he was a Royal Notary and Diocesan Clerk for James IV and James V of Scotland; vicar of the Parishes of Fordyce, Bothelny and Kinkell (1516-1552); five times Rector of King's College – University of Aberdeen; Master of Works on the Bridge of Dee in Aberdeen and for Greyfriars Church in Aberdeen; and Chancellor of the Diocese of Aberdeen. According to Steven Holmes,[1] he was one of the most notable liturgists of his time, designing many fine examples of Sacrament Houses across the North-East of Scotland. He was a friend of and adviser to Hector Boece, the first Principal of the University of Aberdeen, as well as Bishop Elphinstone, Chancellor of Scotland and Gavin Dunbar. He was an avid anti-Reformationist being a friend of Jacobus Latomus and Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus and clerics in the Old University of Leuven. Along with Gavin Dunbar, Galloway designed and had built the western towers of the cathedral and designed the heraldic ceiling, featuring 48 coats of arms in three rows of sixteen. More than anyone else he contributed to the development of the artistry of Scottish lettering.[2] He has a claim to be what some might call "a Renaissance Man".[3]

Background

In 1949, the eminent Aberdeen architect and antiquarian, William Kelly, wrote a brief hagiography and stated:

[..] one of the notable men of Aberdeen in the first half of the sixteenth century: a good man, and a priest; a warm-hearted, open-handed, willing, and managing; one of the brotherhood of artistic men; [..] a deviser of liberal things, by which his figure stands secure in its own niche to this day.

— William Kelly, Aberdeen University Press (1949).[4]

In 2017, Charles Burnett provided an outline of this cleric.[5] A publication by Ray McAleese in 2019 provided a character study of Galloway.[6] Apart from these publications, Galloway is almost invisible in the history of the north-east of Scotland. He was considered by the great reforming Bishop William Elphinstone to be one of his most faithful and able Canons. Hector Boece writing in 1522 a biography of Elphinstone, wrote that Elphinstone ".. hardly did anything without Galloway’s guidance..".[7] There are no public memorials to him apart from references in two stained glass windows by eminent twentieth-century artists – Charles Eamer Kempe and Douglas Strachan. Galloway, when he is recalled is most often remembered as the “architect” of Greyfriars John Knox Church on Broad Street, Aberdeen; the Bridge of Dee; liturgic marks and sacrament houses in Aberdeenshire churches;[8] and finally a striking octagonal baptismal font in St John's, Aberdeen. There are no images of him apart from those provided in glass by Kempe and Strachan.

Family

Little is known of his early history. His father was William Galloway; his mother is named by Kelly as Marjorie Mortimer.[9] Marjorie may have been part of the Mortimer family who at the time were the owners of Craigievar Castle near Aberdeen.[10] Alexander had two brothers. William Galloway was a Carmelite in Aberdeen. A second brother, Andrew Galloway, features in the history of King’s College later in the sixteenth century. Galloway’s father had connections in Angus. This can be seen in the records of St Andrews University where Galloway is recorded as being a matriculated student in 1493.

Galloway almost certainly came as a student to Bishop Elphinstone’s new college (St Mary’s College, later Kings College) in Old Aberdeen (see University of Aberdeen). Later in life he adopted the arms of the namesake family – the Earls of Galloway, a common practice at the time. Alexander Galloway is recorded as "master" Galloway – a graduate in 1499. A priest in the making. Very quickly he emerges from the shadows as a Royal Notary and Diocesan Clerk for the diocese. Rapid progress for such a young priest. In 1503, lays claim to lands at Colyhill, near Chapel of Garioch – the start of his fifty-year connection with the Inverurie area of Aberdeenshire and what was to become his principal parish at Kinkell – two miles from Inverurie.

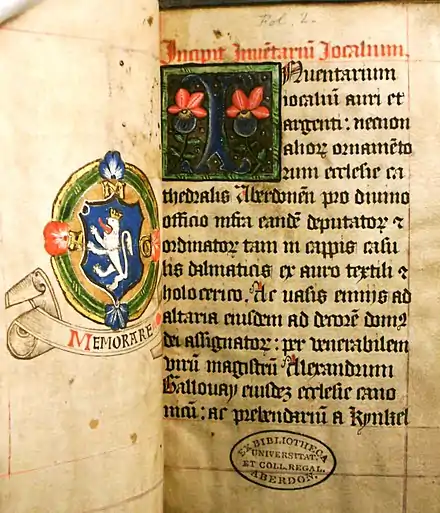

While his family circumstances remain unclear, Galloway had substantial wealth. He used this during his life to fund various projects as well as allowing him to live comfortably in residences in the parish where he was Prebendary (Kinkell) and in the Chanonry in Old Aberdeen. During his lifetime he provided funds to allow scribes to prepare records of the church St Nicholas in Aberdeen, the cathedral of St Machar in Old Aberdeen, and various Rectoral reports for King’s College (University of Aberdeen). It is believed that the 1549 report on his Rectoral “visitation” is in his own hand. He also provided funds to purchase lands for church purposes and in one instance for a Hospital for “Bedeswomen” at the Foot O’Dee in Aberdeen.[11] He took arms sometime after c.1500 that reference Fergus of Galloway.[12] These arms were used by Galloway to decorate many of his liturgical works.[13] They also appear in his own hand on an inventory of St Machar Cathedral.[14]

The Architect

Within the few published references to Galloway, his role in the diocese is most often referred to as an "architect". However, in the 16th century the term had not yet been applied to the role that he played within the Diocese.[15] In common with the way Cathedral Chapters managed the building work in the diocese, a Master of Works or “supervisor” was first appointed by the Bishop. He in turn would have appointed a Master Mason and a Master Carpenter. The Master of Works would also have had a deputy who kept day to day accounts and reported to Cathedral Chapter. In managing building work for the Chapter, a Master of Works would have made use of wooden models and drawings of buildings, bridges etc. made by the Master Carpenter.[16] Galloway was Master of Works for the Diocese from c. 1509 to his death in 1552. He was suited to this potion first, because of a close working relationship to Bishops Elphinstone and Dunbar and his friendship with Hector Boece. Second, his skill in liturgical matters made him a knowledgeable and safe pair of hands.[17] His influence was wider than in the Aberdeen diocese. As an experienced Master of Works he developed a close association with Canon Alexander Mylne of Dunkeld (d.1548), first President of the Scottish College of Justice and Abbot of Cambuskenneth. In that diocese, Mylne supervised, as the Master of Works, the building of the “old” bridge in Dunkeld. This was the same time that Bishop Durbar was revising Bishop Elphinstone’s plans for a bridge over the river Dee. Mylne and Galloway had common interests.[18] Galloway also undertook the role of Master of Works for the great wooden ceiling in the Cathedral, the “Dunbar western towers” of the cathedral, various churches and the Bridge of Dee (1522-1527) in Aberdeen. He was also the Master of Works for Greyfriars Church in Aberdeen and the Snow Kirk in Old Aberdeen.

The Liturgist

Apart from his organisation skills, Galloway was a deeply committed conservative priest. He was a “canonist”. He also left a legacy of buildings, signs and symbols that place him as one of the great 16th century Liturgists in the NE of Scotland.[19] Carter has recalled him as :

[..] the man behind the late flowering of medieval [sic] art which took place in the NE of Scotland during the first third of the 16th century ..[..] .

— Carter, Charles. 1956[20]

Galloway made three important liturgical contributions at his own Church. First a sacrament house (1524). In Scotland the host was most often held in an ambury usually situated at the east end of the sanctuary. His sacrament house at Kinkell is in the form of an ambury on the NE wall. Galloway had visited the Low Countries where there are similar sacrament houses. There he met Jacobus Latomus at Louvain, Belgium[21] The sacrament house at Kinkell can still be seen although it heavily weathered. It is cross-shaped, with the cupboard (ambury) in the lower part. It is decorated with the words HIC EST SEVATUM CORPUS DE VIRGINE NATUM (“Here is preserved the body which was born of a virgin’”) on the panelled compartments forming the arms of the cross. Two angels can be seen holding the monstrance on the centre and at the top of the cross. At the bottom is the date, AD 1524, together with Galloway’s initials. There is considerable damage to the installation due to weathering.[22]

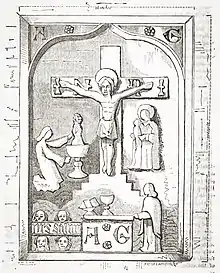

Second, a unique crucifixion plaque (1525). The crucifix scene was designed to show the mass as a re-presentation of the passion. Holmes claims:

[..] .. ..the crucifix suggests that its purpose was to show, in the same way as much liturgical interpretation and medieval Eucharistic theology, that the mass was a re-presentation of the passion…..this plaque gave a Catholic interpretation of the mass for the people in the church … the prominence of Galloway’s initials suggests that he wanted to be remembered for this teaching…....[..]

— Steven Holmes (2015)[23]]]

The panel that is now visible, in the ruins, is a copy made in the early 20th century after the original had been removed for restoration and lost in 1903! The original installation would have been painted and decorated with coloured wires. The Cross is adorned with the liturgic sign INRI. That is, IESVS·NAZARENVS·REX·IVDÆORVM (Iesus Nazarenus, Rex Iudaeorum) "Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews" (John 19:19). To the left of the cross is the Archangel St Michael the patron saint of Kinkell church. To the right the Virgin Mary. Below, to the left, is a representation Souls in Purgatory. Indicating ”preces sanctorum” – prayers for the dead. To the right, below, a figure that was probably Galloway. His initials and the Marian rose are depicted on the altar as well as on the frame of the plaque. Steven Holmes

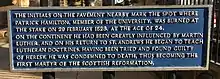

Third, a baptismal font. This can be seen in St John’s Episcopal Church, Crown Terrace in Aberdeen. The bowl is octagonal with sunken panels on each face. This design is striking when compared to other medieval fonts in Scotland.[24] The liturgical signs are as follows: the eight sides of the bowl itself are a reference to the eighth day of Holy Week – the Sunday of the Resurrection and new birth. A striking feature on one side of the bowl is the letters A & G intertwined with a cord.[25] There are in addition on other faces, the Arma Christi (five wounds - the objects associated with Jesus' Passion), two sacred monograms (one being “IHS” - abbreviation of the name ΙΗΣΟΥΣ (Jesus); the other a crowned M for Mary), a pierced heart (the "arms of Mary"), two carved roses and the cross with a crown of thorns. Galloway made extensive use of the Marian Rose in his liturgical signs, as well as being a practicing "Marianist". The bowl, which is 18 in (46 cm) deep and 9.5 in (24 cm) wide has a drain. It now sits on a pedestal which was designed by the Aberdeen architect James Mitchell who provided the setting in 1851 when it was installed in St John's.[26]

A Man of his Times

Not only was Galloway a skilled canonist, Master of Works and an influential liturgist, In two ways he was a "man of his times". First, his ability to hold a view of the world that depends on myth and magic. Some time, between 1505 and 1507 Galloway and Hector Boece undertook a series of expeditions on behalf of Bishop Elphinstone.[27] Elphinstone was making preparations for a new Scottish Breviary. To inform the group undertaking the work, Boece and Galloway, both members of the Aberdeen Liturgists, were asked to update stories of the Scottish Saints.[28] On one of their trips to monasteries and abbeys in the west of Scotland, they reached an island named "Thule" by Boece.[29] There, according to Boece, Galloway gave his views on origins of barnacle geese. (See, Barnacle goose myth)

[..] Alexander Galloway, parson of Kinkell, who, besides being a man of outstanding probity, is possessed of an unmatched zeal for studying wonders … when he was pulling up some driftwood and saw that seashells were clinging to it from one end to the other, he was surprised by the unusual nature of the thing, and, out of a zeal to understand it, opened them up, whereupon he was more amazed than ever, for within them he discovered, not sea creatures, but rather birds, of a size similar to the shells that contained them ... small shells contained birds of a proportionately small size ... so, he quickly ran to me, whom he knew to be gripped with a great curiosity for investigating suchlike matters and revealed the entire thing to me ..[..]

— DF Sutton, Hector Boethius - Scotorum Historia (1575 version)[30]

Boece has been accused of writing history that suited his sponsor, James V of Scotland.[32] In many parts of his history of Sotland, Boece draws on medieval explanations based on myth,[33] The lasting feature was that Boece allowed Galloway to express the view that barnacle geese did come from barnacles. The explanation may involve the geese dropping from trees growing on the sea shore fully formed. Or, emerging from barnacles that clung to flotsam. In either case, Galloway was reflecting what was known about barnacle geese in the 16th century. His certainty about religion was under-scored by his certainty about the natural world.

Second, Galloway had been a frequent visitor to Europe. The Diocese of Aberdeen, under Elphinstone was strongly influenced by scholars from across Europe. Aberdeen had a strong trading link with the Low Countries.

On 28/29 February 1528, Patrick Hamilton, considered the first Scottish martyr of the Reformation, was cruelly burned at the stake in St. Andrews. Hamilton had made the fatal mistake of writing about "the errors and absurdities of the papists", so was seen as a heretic by the conservative liturgist Galloway, his Bishop and the arch-conservative Beaton. It appears that both the Bishop of Aberdeen and his loyal Canon were present at the trial and execution of Hamilton. This came about as follows. Galloway had been a frequent visitor to Old University of Leuven Louvain in Belgium. There he became a friend and supporter of Jacobus Latomus who was an outspoken critic of Erasmus. Latomus referred to ‘Alexander Galoai Scotus Abordonensis canonicus’ as one of the ‘friends’ who persuaded him to publish his reply to Patrick Hamilton's Places.[34]

After the burning, Galloway wrote to his friends in Louvain reporting on the "success" of the trial.[35] Lorimer says:

[..] …When informed of the event by Alexander Galloway, canon of Aberdeen, the doctors of Louvain were filled with a cruel joy, and wrote to (James) Beaton to thank him for his services to the common faith, … [..]

— Patrick Hamilton, the First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation: an historical biography[36]

These events and connections are circumstantial; however, the events provide a pointer to an important facet of Galloway’s character. He certainly was more than just the liturgist and Master of Works. Galloway’s liturgical zeal indicates a preference for certainty and deep conservatism. Further, he was prepared to write to others about what he thought. Perhaps it was this conservatism that drove his liturgical zeal. He was "a man of his times with many virtues and a few crimes"(sic)

References

- Holmes, Stephen Mark (2015), Sacred Signs in Reformation Scotland : interpreting worship, 1488-1590

- Harrison, A & Burnett, C J. 2017. 'Scottish Lettering of the 16th century', Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, 147: 219-37.

- McAleese, R. 2019 'Canon Alexander Galloway – Scholar, Priest, or “Renaissance Man” (c1478x1552) ', Scottish Local History, 102: 13-20.

- William Kelly, Alexander Galloway, Rector of Kinkell, Aberdeen University Studies. No. 125 (Aberdeen: The University Press, 1949), pp. 19-33.

- Charles Burnett, 'Alexander Galloway: A Remarkable Aberdeen Cleric', Leopard (2017), 44-46.

- McAleese, R. (2019). "Canon Alexander Galloway – Scholar, Priest, or “Renaissance Man” (c1478x1552) Scottish Local History Journal 102: 13-20.

- Boece, Hector. 1522. Episcoporum Murthlacen et Aberdonen vitae (Paris), p.92.

- see, Holmes, S. M. (2015). Sacred signs in Reformation Scotland: interpreting worship, 1488-1590.

- A reference in Registrum Episcopatus Aberdonensis, In the Kalendar of Obituaries, V2, P6, lists Wilelmi Gallouay and Mariorie Mortimar as his father and mother – the anniversary is 6 March. See https://archive.org/details/registrumepiscop02aber/page/n27

- There is a strong similarity between the arms of the Mortimer family of Craigievar and those of the Earls of Galloway both of which use the lion rampant as part of their arms. Some of the Mortimer "clan" owned Craigievar Castle, some 20 miles from Aberdeen, in the 15th century. No conclusive evidence can link this family to Galloway’s mother. Marjorie Mortimer may have come from Angus.

- Richard Oram p.22, fn.30 in, British Archaeological Association. Conference (2014 : Aberdeen Scotland), J. Geddes, J. Geddes, and British Archaeological Association. 2016. Medieval art, architecture and archaeology in the dioceses of Aberdeen and Moray (Routledge: London)

- Galloway's Arms are based on the ancient Arms of the Earls of Galloway and can be blazoned ‘Azure, a lion rampant Argent, langued Gules, crowned Or’. His motto was 'memorare' (remember). The letters A G surmount the shield.

- https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/kinkell-church/history/

- In the University of Abderdeen Library, ‘Inventarium jocalium necnon aliorum ornamentum Cathedralis ecclesiae Aberdonensis’ GB0231/ MS 250.

- Pevsner, N. 1942. 'The Term "architect" in the Middle Ages', Spectrum, 17: 549-62.

- Knoop, D. and Peredur Jones, G., The Medieval Mason : An Economic History of English Stone Building in the Later Middle Ages and Early Modern Times. 3rd edn. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1967).

- Holmes, Stephen Mark. 2015. Sacred signs in Reformation Scotland : interpreting worship, 1488-1590.

- Later this friendship led to their close association in opposition to the Reformation when Mylne was Abbot of Cambuskenneth. See, Watt, D, E, R.; Shead, N. F., eds. (2001). The Heads of Religious Houses in Scotland from Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries. Edinburgh: The Scottish Record Society. ISBN 0 902054 18 X. Mylne was part of the “jury” that condemned Patrick Hamilton (martyr) when he was tried and cruelly executed in St Andrews in 1528.

- Carter, Charles. 1956. 'The Arma Christi in Scotland', Proceeding of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 90: 116-29.

- 'The Arma Christi in Scotland', Proceeding of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 90: 116-29.

- It was Latomus who encouraged Galloway in his opposition to the teaching of Patrick Hamilton who held a Lutheran doctrine of the eucharist. This doctrine would have been seen by Galloway to be at variance with his own.

- The Church was abandoned by the Church of Scotland in 1771.

- Holmes, Stephen Mark. 2015. Sacred signs in Reformation Scotland : interpreting worship, 1488-1590.

- Walker, Russell. 1887. 'Scottish Baptismal Fonts. With Drawings', Proceeding of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 21: 346-448.

- It was not uncommon for church sponsors to mark their gift with a shield or a monogram. Galloway used the intertwined chord on a number of occasions.

- The church at Kinkell was abandoned in the 18th. century. In the early 19th. Century, the bowl was removed from Kinkell to Aberdeen by Alexander Dauney (1776-1833), the son of Rev. Francis Dauney, Professor of Divinity and Principle of Mariscal College (University of Aberdeen. Dauney was a lawyer, honorary burgess of Old Aberdeen and the first Secretary of the Aberdeenshire Canal Company. He built an imposing house with an extensive garden in a desirable part of Aberdeen known as the House of Rubislaw Den. He had the font taken from Kinkell and placed in his garden where it languished until its translation to St. John’s in 1851

- These trips have not been confirmed in any documentary source. It is likely that trips may have been made the different members of the Aberdeen Liturgists. The evidence for Boece and Galloway’s trip is in part based on the dialogue reported by Boece in his Historia Scotorum. Boece used speech and dialogue across his Scottish writing to highlight or give body to historical events. This technique was used by other historiography writers such as the poet Barbour and Bower. It is based on a style used by the Roman historian Livy. Boece’s stylistic approach leaves the possibility of these trip open to question. See, Royan, Nicola. 2000. 'The Uses of Speech in Hector Boece’s Scotorum historia.' in L. A. J. R. Houwen, MacDonald, A. A., Mapstone, Sally (ed.), A palace in the wild : essays on vernacular culture and humanism in late-medieval and Renaissance Scotland (Peeters: Leuven).

- In the Royal Patent for the printing of the Breviary there is a reference to the collection of stories about Saints. See, Matthew Livingstone, David Hay Fleming, James Beveridge, and Gordon Donaldson (1908). Registrum secreti sigilli regum Scotorum; the register of the Privy seal of Scotland (H.M. General Register House: Edinburgh,)v.1. 1488-1529, 1546, 15th Sept. 1507, pp 223-224; also, Holmes, Stephen Mark. 2015. Sacred Signs in Reformation Scotland: interpreting worship 1488-1590, pp 61, fn. 37.

- The name Thule refers to the western edge of the known world according to Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius (Boethius) a sixth-century philosopher - not to be confused with Galloway’s colleague Hector Boece. It is possible that Boece was thinking of Islay.

- http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/boece/

- The account of this conversation is in all but one editions of Boece’s “Historiae a prima gentis origine” in the Cosmology Introduction. SeeBarnacle goose myth

- see various accounts in Royan, Nicola Rose. 1996. 'The Scotirum Historia of Hector Boece’, PhD, University of Oxford (1996)

- For example, his references to the witches – later appearing in William Shakespeare's play, Macbeth provides evidence about the veracity of Boece’s account of Thule and, perhaps the conversation on barnacle geese. The account of the barnacle geese involving Galloway and Boece reflects not only Galloway’s views, but the world as seen by Pre-Reformation scholars.

- https://www.exclassics.com/foxe/foxe166.htm

- Evidence is provided in: J Knox, D Laing and Woodrow Society, The Works of John Knox. 6 vols (Printed for the Woodrow Society, Edinburgh, 1846), vol.1, pp 43-4; and P Lorimer, Patrick Hamilton, the First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation: an historical biography, collected from original sources, with an Appendix of Original Letters and Other Papers (Constable, Edinburgh, 1857).

- Patrick Hamilton, the First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation: an historical biography, collected from original sources, with an Appendix of Original Letters and Other Papers (Constable, Edinburgh, 1857).