Capacitor plague

The capacitor plague was a problem related to a higher-than-expected failure rate of non-solid aluminium electrolytic capacitors, between 1999 and 2007, especially those from some Taiwanese manufacturers,[1][2] due to faulty electrolyte composition that caused corrosion accompanied by gas generation, often rupturing the case of the capacitor from the build-up of pressure.

High failure rates occurred in many well-known brands of electronics, and were particularly evident in motherboards, video cards, and power supplies of personal computers.

History

First announcements

The first flawed capacitors linked to Taiwanese raw material problems were reported by the specialist magazine Passive Component Industry in September 2002.[1] Shortly thereafter, two mainstream electronics journals reported the discovery of widespread prematurely failing capacitors, from Taiwanese manufacturers, in motherboards.[3][4]

These publications informed engineers and other technically interested specialists, but the issue did not receive widespread public exposure until Carey Holzman published his experiences about "leaking capacitors" in the overclocking performance community.[5]

Public attention

The news from the Holzman publication spread quickly on the Internet and in newspapers, partly due to the spectacular images of the failures – bulging or burst capacitors, expelled sealing rubber and leaking electrolyte on countless circuit boards. Many PC users were affected, and caused an avalanche of reports and comments on thousands of blogs and other web communities.[4][6][7]

The quick spread of the news also resulted in many misinformed users and blogs posting pictures of capacitors that had failed due to reasons other than faulty electrolyte.[8]

Prevalence

Most of the affected capacitors were produced from 1999 to 2003 and failed between 2002 and 2005. Problems with capacitors produced with an incorrectly formulated electrolyte have affected equipment manufactured up to at least 2007.[2]

Major vendors of motherboards such as Abit,[9] IBM,[1] Dell,[10] Apple, HP, and Intel[11] were affected by capacitors with faulty electrolytes.

In 2005, Dell spent some US$420 million replacing motherboards outright and on the logistics of determining whether a system was in need of replacement.[12][13]

Many other equipment manufacturers unknowingly assembled and sold boards with faulty capacitors, and as a result the effect of the capacitor plague could be seen in all kinds of devices worldwide.

Because not all manufacturers had offered recalls or repairs, do-it-yourself repair instructions were written and published on the Internet.[14]

Responsibility

In the November/December 2002 issue of Passive Component Industry, following its initial story about defective electrolyte, reported that some large Taiwanese manufacturers of electrolytic capacitors were denying responsibility for defective products.[15]

While industrial customers confirmed the failures, they were not able to trace the source of the faulty components. The defective capacitors were marked with previously unknown brands such as "Tayeh", "Choyo", or "Chhsi".[16] The marks were not easily linked to familiar companies or product brands.

The motherboard manufacturer ABIT Computer Corp. was the only affected manufacturer that publicly admitted to defective capacitors obtained from Taiwan capacitor makers being used in its products.[15] However, the company would not reveal the name of the capacitor maker that supplied the faulty products.

Industrial espionage

A 2003 article in The Independent claimed that the cause of the faulty capacitors was in fact due to a mis-copied formula. In 2001, a scientist working in the Rubycon Corporation in Japan stole a mis-copied formula for capacitors' electrolytes. He then took the faulty formula to the Luminous Town Electric company in China, where he had previously been employed. In the same year, the scientist's staff left China, stealing again the mis-copied formula and moving to Taiwan, where they would have created their own company, producing capacitors and propagating even more of this faulty formula of capacitor electrolytes.[17]

Symptoms

Common characteristics

The non-solid aluminium electrolytic capacitors with improperly formulated electrolyte mostly belonged to the so-called "low equivalent series resistance (ESR)", "low impedance", or "high ripple current" e-cap series. The advantage of e-caps using an electrolyte composed of 70% water or more is, in particular, a low ESR, which allows a higher ripple current, and decreased production costs, water being the least costly material in a capacitor.[18]

| Electrolyte | Manufacturer series, type |

Dimensions D × L (mm) |

Max. ESR at 100 kHz, 20 °C (mΩ) |

Max. ripple current at 85/105 °C (mA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-solid organic electrolyte | Vishay 036 RSP, 100 µF, 10 V | 5 × 11 | 1000 | 160 |

| Non-solid, ethylene-glycol, boric-acid (borax) electrolyte | NCC SMQ, 100 µF, 10 V | 5 × 11 | 900 | 180 |

| Non-solid water-based electrolyte | Rubycon ZL, 100 µF, 10 V | 5 × 11 | 300 | 250 |

Premature failure

All electrolytic capacitors with non-solid electrolyte age over time, due to evaporation of the electrolyte. The capacitance usually decreases and the ESR usually increases. The normal lifespan of a non-solid electrolytic capacitor of consumer quality, typically rated at 2000 h/85 °C and operating at 40 °C, is roughly 6 years. It can be more than 10 years for a 1000 h/105 °C capacitor operating at 40 °C. Electrolytic capacitors that operate at a lower temperature can have a considerably longer lifespan.

The capacitance should normally degrade to as low as 70% of the rated value, and the ESR increase to twice the rated value, over the normal life span of the component, before it should be considered as a "degradation failure".[19][20] The life of an electrolytic capacitor with defective electrolyte can be as little as two years. The capacitor may fail prematurely after reaching approximately 30% to 50% of its expected lifetime.

Electrical symptoms

The electrical characteristics of a failed electrolytic capacitor with an open vent are the following:

- capacitance value decreases to below the rated value

- ESR increases to very high values.

Electrolytic capacitors with an open vent are in the process of drying out, regardless of whether they have good or bad electrolyte. They always show low capacitance values and very high ohmic ESR values. Dry e-caps are therefore electrically useless.

E-caps can fail without any visible symptoms. Since the electrical characteristics of electrolytic capacitors are the reason for their use, these parameters must be tested with instruments to definitively decide if the devices have failed. But even if the electrical parameters are out of their specifications, the assignment of failure to the electrolyte problem is not a certainty.

Non-solid aluminium electrolytic capacitors without visible symptoms, which have improperly formulated electrolyte, typically show two electrical symptoms:

- relatively high and fluctuating leakage current[21][22]

- increased capacitance value, up to twice the rated value, which fluctuates after heating and cooling of the capacitor body

Visible symptoms

When examining a failed electronic device, the failed capacitors can easily be recognized by clearly visible symptoms that include the following:[23]

- Bulging of the vent on top of the capacitor. (The "vent" is stamped into the top of the casing of a can-shaped capacitor, forming a seam that is meant to split to relieve pressure build-up inside, preventing an explosion.)

- Broken or cracked vent, often accompanied with visible crusty rust-like brown or red dried electrolyte deposits.

- Capacitor casing sitting crooked on the circuit board, caused by the bottom rubber plug being pushed out, sometimes with electrolyte having leaked onto the motherboard from the base of the capacitor, visible as dark-brown or black surface deposits on the PCB.[24] The leaked electrolyte can be confused with thick elastic glue sometimes used to secure the capacitors against shock. A dark brown or black crust up the side of a capacitor is invariably glue, not electrolyte. The glue itself is harmless.

- Visible symptoms of failed electrolytic capacitors

Failed Chhsi capacitor with crusty electrolyte buildup on the top

Failed Chhsi capacitor with crusty electrolyte buildup on the top Failed capacitors next to CPU motherboard socket

Failed capacitors next to CPU motherboard socket Failed Tayeh capacitors which have vented subtly through their aluminium tops

Failed Tayeh capacitors which have vented subtly through their aluminium tops Failed electrolytic capacitors with swollen can tops and expelled rubber seals, dates of manufacture "0106" and "0206" (June 2001 and June 2002)

Failed electrolytic capacitors with swollen can tops and expelled rubber seals, dates of manufacture "0106" and "0206" (June 2001 and June 2002) Failed capacitor has exploded and exposed internal elements, and another has partially blown off its casing

Failed capacitor has exploded and exposed internal elements, and another has partially blown off its casing Failed Choyo capacitors (black color) which have leaked brownish electrolyte onto the motherboard

Failed Choyo capacitors (black color) which have leaked brownish electrolyte onto the motherboard

Non-solid aluminium electrolytic capacitors

The first electrolytic capacitor developed was an aluminium electrolytic capacitor with a liquid electrolyte, invented by Charles Pollak in 1896. Modern electrolytic capacitors are based on the same fundamental design. After roughly 120 years of development billions of these inexpensive and reliable capacitors are used in electronic devices.

Basic construction

- Basic construction details of non-solid aluminium electrolytic capacitors

Construction of a typical single-ended aluminium electrolytic capacitor with non-solid electrolyte

Construction of a typical single-ended aluminium electrolytic capacitor with non-solid electrolyte Closeup cross-section diagram of electrolytic capacitor, showing capacitor foils and oxide layers

Closeup cross-section diagram of electrolytic capacitor, showing capacitor foils and oxide layers

Aluminium electrolytic capacitors with non-solid electrolyte are generally called "electrolytic capacitors" or "e-caps". The components consist of two strips of aluminium foil, separated by a paper spacer, which is saturated with a liquid or gel-like electrolyte. One of the aluminium foil strips, called the anode, chemically roughened and oxidized in a process called forming, holds a very thin oxide layer on its surface as an electrical insulator serving as the dielectric of the capacitor. The liquid electrolyte, which is the cathode of the capacitor, covers the irregular surface of the oxide layer of the anode perfectly, and makes the increased anode surface effectual, thus increasing the effective capacitance.

A second aluminium foil strip, called the "cathode foil", serves to make electrical contact with the electrolyte. The spacer separates the foil strips to avoid direct metallic contact which would produce a short circuit. Lead wires are attached to both foils which are then rolled with the spacer into a wound cylinder which will fit inside an aluminium case or "can". The winding is impregnated with liquid electrolyte. This provides a reservoir of electrolyte to extend the lifetime of the capacitor. The assembly is inserted into an aluminium can and sealed with a plug. Aluminium electrolytic capacitors with non-solid electrolyte have grooves in the top of the case, forming a vent, which is designed to split open in the event of excessive gas pressure caused by heat, short circuit, or failing electrolyte.

Forming the aluminium-oxide dielectric

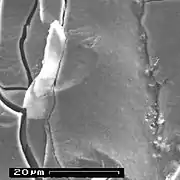

- View onto the structures of a low-voltage anode foil

Cross-section side view of etched 10 V low voltage anode foil

Cross-section side view of etched 10 V low voltage anode foil SEM image of the rough anode surface of an unused electrolytic capacitor, showing the openings of pores in the anode

SEM image of the rough anode surface of an unused electrolytic capacitor, showing the openings of pores in the anode Ultra-thin-cross-section of an etched pore in a low-voltage anode foil, 100,000-fold magnification, light grey: aluminium, dark grey: amorphous aluminium oxide, light: pore, in which the electrolyte is active

Ultra-thin-cross-section of an etched pore in a low-voltage anode foil, 100,000-fold magnification, light grey: aluminium, dark grey: amorphous aluminium oxide, light: pore, in which the electrolyte is active

The aluminium foil used in non-solid aluminium electrolytic capacitors must have a purity of 99.99%. The foil is roughened by electrochemical etching to enlarge the effective capacitive surface. This etched anode aluminium foil is oxidized (called forming). Forming creates a very thin oxide barrier layer on the anode surface. This oxide layer is electrically insulating and serves as the dielectric of the capacitor. The forming takes place whenever a positive voltage is applied to the anode, and generates an oxide layer whose thickness varies according to the applied voltage. This electrochemical behavior explains the self-healing mechanism of non-solid electrolytic capacitors.

The normal process of oxide formation or self-healing is carried out in two reaction steps.[25] First, a strongly exothermic reaction transforms metallic aluminium (Al) into aluminium hydroxide, Al(OH)3:

- 2 Al + 6 H2O → 2 Al(OH)3 + 3 H2 ↑

This reaction is accelerated by a high electric field and by high temperatures, and is accompanied by a pressure buildup in the capacitor housing, caused by the released hydrogen gas. The gel-like aluminium hydroxide Al(OH)3 (also called alumina trihydrate (ATH), aluminic hydroxide, aluminium(III) hydroxide, or hydrated alumina) is converted, via a second reaction step (usually slowly over a few hours at room temperature, more rapidly in a few minutes at higher temperatures), into the amorphous or crystalline form of aluminium oxide, Al2O3:

- 2 Al(OH)3 → 2 AlO(OH) + 2 H2O → Al2O3 + 3 H2O

This oxide serves as dielectric and also protects the capacitor from the aggressive reactions of metallic aluminium to parts of the electrolyte. One problem of the forming or self-healing processes in non-solid aluminium electrolytics is that of corrosion, the electrolyte having to deliver enough oxygen to generate the oxide layer, with water, corrosive of aluminium, being the most efficient way.

Electrolyte composition

The name "electrolytic capacitor" derives from the electrolyte, the conductive liquid inside the capacitor. As a liquid it can conform to the etched and porous structure of the anode and the grown oxide layer, and form a "tailor-made" cathode.

From an electrical point of view the electrolyte in an electrolytic capacitor is the actual cathode of the capacitor and must have good electrical conductivity, which is actually ion-conductivity in liquids. But it is also a chemical mixture of solvents with acid or alkali additives,[26] which must be non-corrosive (chemically inert) so that the capacitor, whose inner components are made of aluminium, remains stable over its expected lifetime. In addition to the good conductivity of operating electrolytes, there are other requirements, including chemical stability, chemical compatibility with aluminium, and low cost. The electrolyte should also provide oxygen for the forming processes and self-healing. This diversity of requirements for the liquid electrolyte results in a broad variety of proprietary solutions, with thousands of patented electrolytes.

Up to the mid 1990s electrolytes could be roughly placed into two main groups:

- electrolytes based on ethylene glycol and boric acid. In these so-called glycol or borax electrolytes, an unwanted chemical crystal water reaction occurs: "acid + alcohol gives ester + water". These borax electrolytes have been standard in electrolytic capacitors for a long time, and have a water content between 5 and 20%. They work up to a maximum temperature of 85 °C or 105 °C in the voltage range up to 600 V.[27]

- almost anhydrous electrolytes based on organic solvents, such as dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethylacetamide (DMA), or γ-butyrolactone (GBL). These capacitors with organic-solvent electrolytes are suitable for temperatures ranging up to 105 °C, 125 °C, or 150 °C; have low leakage current values; and have very good long-term behavior.

It was known that water is a very good solvent for low ohmic electrolytes. However, the corrosion problems linked to water hindered, up to that time, the use of it in amounts larger than 20% of the electrolyte, the water-driven corrosion using the above-mentioned electrolytes being kept under control with chemical inhibitors that stabilize the oxide layer.[28][29][30][31]

Water-based electrolyte capacitors

In the 1990s a third class of electrolytes was developed by Japanese researchers.

- Water-based electrolytes, with up to 70% water, are relatively inexpensive and boast desirable characteristics such as low ESR and higher voltage handling. These electrolytic capacitors are typically labeled "low-impedance", "low-ESR", or "high-ripple-current" with voltage ratings up to 100 V,[18] for low-cost mass-market applications.

- Despite these advantages, researchers faced several challenges during development of water-based electrolytic capacitors.

- Many of the poorly designed capacitors made it to mass market. The capacitor plague is due to faulty electrolytes of this type.

Development of a water-based electrolyte

At the beginning of the 1990s, some Japanese manufacturers started the development of a new, low-ohmic water-based class of electrolytes. Water, with its high permittivity of ε = 81, is a powerful solvent for electrolytes, and possesses high solubility for conductivity-enhancing concentrations of salt ions, resulting in significantly improved conductivity compared to electrolytes with organic solvents like GBL. But water will react quite aggressively and even violently with unprotected aluminium, converting metallic aluminium (Al) into aluminium hydroxide (Al(OH)3), via a highly exothermic reaction that gives off heat, causing gas expansion that can lead to an explosion of the capacitor. Therefore, the main problem in the development of water-based electrolytes is achieving long-term stability by hindering the corrosive action of water on aluminium.

Normally the anode foil is covered by the dielectric aluminium oxide (Al2O3) layer, which protects the base aluminium metal against the aggressiveness of aqueous alkali solutions. However, some impurities or weak points in the oxide layer offer the possibility for water-driven anodic corrosion that forms aluminium hydroxide (Al(OH)3). In e-caps using an alkaline electrolyte this aluminium hydroxide will not be transformed into the desired stable form of aluminium oxide. The weak point remains and the anodic corrosion is ongoing. This corrosive process can be interrupted by protective substances in the electrolyte known as inhibitors or passivators.[31][32] Inhibitors—such as chromates, phosphates, silicates, nitrates, fluorides, benzoates, soluble oils, and certain other chemicals—can reduce the anodic and cathodic corrosion reactions. However, if inhibitors are used in an insufficient amount, they tend to increase pitting.[33]

The water problem in non-solid aluminium electrolytic capacitors

The aluminium oxide layer in the electrolytic capacitor is resistant to chemical attacks, as long as the pH value of the electrolyte is in the range of pH 4.5 to 8.5.[34] However, the pH value of the electrolyte is ideally about 7 (neutral); and measurements carried out as early as the 1970s have shown that leakage current is increased, due to chemically induced defects, when the pH value deviates from this ideal value.[35] It is known that water is extremely corrosive to pure aluminium and introduces chemical defects. It is further known that unprotected aluminium oxide dielectrics can be slightly dissolved by alkaline electrolytes, weakening the oxide layer.[36]

The fundamental issue of water-containing-electrolyte systems lies in the control of aggressiveness of the water towards metallic aluminium. This issue has dominated the development of electrolytic capacitors over many decades.[37] The first commercially used electrolytes in the mid-twentieth century were mixtures of ethylene glycol and boric acid. But even these glycol electrolytes had an unwanted chemical water-crystal reaction, according to the scheme: "acid + alcohol" → "ester + water". Thus, even in the first apparently water-free electrolytes, esterification reactions could generate a water content of up to 20 percent. These electrolytes had a voltage-dependent life span, because at higher voltages the leakage current based on the aggressiveness of the water would increase exponentially; and the associated increased consumption of electrolyte would lead to a faster drying out.[19][20] Otherwise, the electrolyte has to deliver the oxygen for self-healing processes, and water is the best chemical substance to do that.[18]

Water-driven corrosion: aluminium hydroxide

in a pore of a roughened electrolytic capacitor anode foil

It is known that the "normal" course of building a stable aluminium oxide layer by the transformation of aluminium, through the intermediate step of aluminium hydroxide, can be interrupted by an excessively alkaline or basic electrolyte. For example, alkaline disruption of the chemistry of this reaction results instead in the following reaction:

- 2 Al (s) + 2 NaOH (aq) + 6 H2O → 2 Na+ (aq) + 2[Al(OH)4]− (s) + 3 H2 (g)

In this case, it may happen that the hydroxide formed in the first step becomes mechanically detached from the metallic aluminium surface and will not be transformed into the desired stable form of aluminium oxide.[38] The initial self-healing process for building a new oxide layer is prevented by a defect or a weak dielectric point, and generated hydrogen gas escapes into the capacitor. Then, at the weak point, further formation of aluminium hydroxide is started, and prevented from converting into stable aluminium oxide. The self-healing of the oxide layer inside the electrolytic capacitor can not take place. However, reactions do not come to a standstill, as more and more hydroxide grows in the pores of the anode foil, and the first reaction step produces more and more hydrogen gas in the can, increasing the pressure.

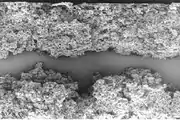

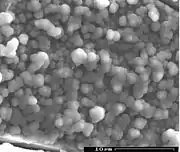

- Scanning electron microscope images

of different forms of aluminium hydroxide

out of failed electrolytic capacitors

Anode surface with grown plaques of aluminium hydroxide

Anode surface with grown plaques of aluminium hydroxide Anode surface with grown beads of aluminium hydroxide

Anode surface with grown beads of aluminium hydroxide

Manufacturing for market

The Japanese manufacturer Rubycon became a leader in the development of new water-based electrolyte systems with enhanced conductivity in the late 1990s. After several years of development, researchers led by Shigeru Uzawa had found a mixture of inhibitors that suppressed the aluminium hydration. In 1998, Rubycon announced two series, ZL and ZA, of the first production capacitors using an electrolyte with a water content of about 40%, which were suitable for temperatures ranging from −40 °C (−40 °F; 233 K) to 105 °C (221 °F; 378 K). Later, electrolytes were developed to work with water of up to 70% by weight. Other manufacturers, such as NCC,[39] Nichicon,[40] and Elna[41] followed with their own products a short time later.

The improved conductivity of the new electrolyte can be seen by comparing two capacitors, both of which have a nominal capacitance of 1000 μF at 16 V rated voltage, in a package with a diameter of 10 mm and a height of 20 mm. The capacitors of the Rubycon YXG series are provided with an electrolyte based on an organic solvent and can attain an impedance of 46 mΩ when loaded with a ripple current of 1400 mA. ZL series capacitors with the new water-based electrolyte can attain an impedance of 23 mΩ with a ripple current of 1820 mA, an overall improvement of 30%.

The new type of capacitor was called "Low-ESR" or "Low-Impedance", "Ultra-Low-Impedance" or "High-Ripple Current" series in the data sheets. The highly competitive market in digital data technology and high-efficiency power supplies rapidly adopted these new components because of their improved performance. Furthermore, by improving the conductivity of the electrolyte, capacitors not only can withstand a higher ripple current rating, they are much cheaper to produce since water is much cheaper than other solvents. Better performance and low cost drove widespread adoption of the new capacitors for high volume products such as PCs, LCD screens, and power supplies.

Investigation

Implications of industrial espionage

Industrial espionage was implicated in the capacitor plague, in connection with the theft of an electrolyte formula. A materials scientist working for Rubycon in Japan left the company, taking the secret water-based electrolyte formula for Rubycon's ZA and ZL series capacitors, and began working for a Chinese company. The scientist then developed a copy of this electrolyte. Then, some staff members who defected from the Chinese company copied an incomplete version of the formula and began to market it to many of the aluminium electrolytic manufacturers in Taiwan, undercutting the prices of the Japanese manufacturers.[1][42] This incomplete electrolyte lacked important proprietary ingredients which were essential to the long-term stability of the capacitors[4][23] and was unstable when packaged in a finished aluminium capacitor. This faulty electrolyte allowed the unimpeded formation of hydroxide and produced hydrogen gas.[36]

There are no known public court proceedings related to alleged theft of electrolyte formulas. However, one independent laboratory analysis of defective capacitors has shown that many of the premature failures appear to be associated with high water content and missing inhibitors in the electrolyte, as described below.

Incomplete electrolyte formula

Unimpeded formation of hydroxide (hydration) and associated hydrogen gas production, occurring during "capacitor plague" or "bad capacitors" incidents involving the failure of large numbers of aluminium electrolytic capacitors, has been demonstrated by two researchers at the Center for Advanced Life Cycle Engineering of the University of Maryland who analyzed the failed capacitors.[36]

The two scientists initially determined, by ion chromatography and mass spectrometry, that there was hydrogen gas present in failed capacitors, leading to bulging of the capacitor's case or bursting of the vent. Thus it was proved that the oxidation takes place in accordance with the first step of aluminium oxide formation.

Because it has been customary in electrolytic capacitors to bind the excess hydrogen by using reducing or depolarizing compounds, such as aromatic nitrogen compounds or amines, to relieve the resulting pressure, the researchers then searched for compounds of this type. Although the analysis methods were very sensitive in detecting such pressure-relieving compounds, no traces of such agents were found within the failed capacitors.

In capacitors in which the internal pressure build-up was so great that the capacitor case was already bulging but the vent had not opened yet, the pH value of the electrolyte could be measured. The electrolyte of the faulty Taiwanese capacitors was alkaline, with a pH of between 7 and 8. Good comparable Japanese capacitors had an electrolyte that was acidic, with a pH of around 4. As it is known that aluminium can be dissolved by alkaline liquids, but not that which is mildly acidic, an energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX or EDS) fingerprint analysis of the electrolyte of the faulty capacitors was made, which detected dissolved aluminium in the electrolyte.

To protect the metallic aluminium against the aggressiveness of the water, some phosphate compounds, known as inhibitors or passivators, can be used to produce long-term stable capacitors with high-aqueous electrolytes. Phosphate compounds are mentioned in patents regarding electrolytic capacitors with aqueous electrolytic systems.[43] Since phosphate ions were missing and the electrolyte was also alkaline in the investigated Taiwanese electrolytes, the capacitor evidently lacked any protection against water damage, and the formation of more-stable alumina oxides was inhibited. Therefore, only aluminium hydroxide was generated.

The results of chemical analysis were confirmed by measuring electrical capacitance and leakage current in a long-term test lasting 56 days. Due to the chemical corrosion, the oxide layer of these capacitors had been weakened, so after a short time the capacitance and the leakage current increased briefly, before dropping abruptly when gas pressure opened the vent. The report of Hillman and Helmold proved that the cause of the failed capacitors was a faulty electrolyte mixture used by the Taiwanese manufacturers, which lacked the necessary chemical ingredients to ensure the correct pH of the electrolyte over time, for long-term stability of the electrolytic capacitors. Their further conclusion, that the electrolyte with its alkaline pH value had the fatal flaw of a continual buildup of hydroxide without its being converted into the stable oxide, was verified on the surface of the anode foil both photographically and with an EDX-fingerprint analysis of the chemical components.

See also

References

- D. M. Zogbi (September 2002). "Low-ESR Aluminium Electrolytic Failures Linked to Taiwanese Raw Material Problems" (PDF). Passive Component Industry. Paumanok Publications. 4 (5): 10, 12, 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- The Capacitor Plague, Posted on 26 November 2010 by PC Tools

- Sperling, Ed; Soderstrom, Thomas; Holzman, Carey (October 2002). "Got Juice?". EE Times.

- Chiu, Yu-Tzu; Moore, Samuel K (February 2003). "Faults & Failures: Leaking capacitors muck up motherboards". IEEE Spectrum. 40 (2): 16–17. doi:10.1109/MSPEC.2003.1176509. ISSN 0018-9235. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- Carey Holzman, Overclockers, Capacitors: Not Just For Abit Owners, Motherboards with leaking capacitors, 10/9, 2002,

- Hales, Paul (5 November 2002). "Taiwanese component problems may cause mass recalls". The Inquirer. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- Capacitor failures plague motherboard vendors, GEEK, 7 February 2003

- W. BONOMO, G. HOOPER, D. RICHARDSON, D. ROBERTS, and TH. VAN DE STEEG, Vishay Intertechnology, Failure modes in capacitors,

- "Mainboardhersteller steht für Elko-Ausfall gerade", Heise (in German) (online ed.), DE.

- Michael Singer, CNET News, Bulging capacitors haunt Dell, 31 October 2005

- Michael Singer, CNET News, PCs plagued by bad capacitors

- The guardian technology blog, How a stolen capacitor formula ended up costing Dell $300m

- Vance, Ashlee (28 June 2010). "Suit Over Faulty Computers Highlights Dell's Decline". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- Repair and bad capacitor information, Capacitor Lab.

- Liotta, Bettyann (November 2002). "Taiwanese Cap Makers Deny Responsibility" (PDF). Passive Component Industry. Paumanok Publications. 4 (6): 6, 8–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- "Capacitor plague, identifizierte Hersteller (~identified vendors)". Opencircuits.com. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Arthur, Charles (31 May 2003). "Stolen formula for capacitors causing computers to burn out". Business News. The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Uzawa, Shigeru; Komatsu, Akihiko; Ogawara, Tetsushi; Rubycon Corporation (2002). "Ultra Low Impedance Aluminium Electrolytic Capacitor with Water based Electrolyte". Journal of Reliability Engineering Association of Japan. 24 (4): 276–283. ISSN 0919-2697. Accession number 02A0509168.

- "A. Albertsen, Electrolytic Capacitor Lifetime Estimation" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Sam G. Parler, Cornell Dubilier, Deriving Life Multipliers for Electrolytic Capacitors

- The Aluminium Electrolytic Condenser, H. 0. Siegmund, Bell System Technical Journal, v8, 1. January 1229, pp. 41–63

- A. Güntherschulze, H. Betz, Elektrolytkondensatoren, Verlag Herbert Cram, Berlin, 2. Auflage 1952

- "Motherboard Capacitor Problem Blows Up". Silicon Chip. AU. 11 May 2003. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

- Blown, Burst and Leaking Motherboard Capacitors - A Serious Problem, PCSTATS, 15 January 2005 Archived 16 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Sundoc Bibliothek, Universität Halle, Dissertation, Aluminium anodization,

- Elna, Principles, 3. Electrolyte, Table 2: An Example of the Composition of the Electrolyte "Aluminium electrolytic capacitors - Principles | ELNA". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- NON-AQUEOUS ELECTROLYTES and THEIR CHARACTERISTICS, FaradNet Electrolytic Capacitors, Part III: Chapter 10 Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- K. H. Thiesbürger: Der Elektrolyt-Kondensator. 4. Auflage. Roederstein, Landshut 1991, [OCLC31349250]

- W. J. Bernard, J. J. Randall Jr., The Reaction between Anodic Aluminium Oxide and Water,

- Ch. Vargel, M. Jacques, M. P. Schmidt, Corrosion of Aluminium, 2004 Elsevier B.V., ISBN 978-0-08-044495-6

- Alfonso Berduque, Zongli Dou, Rong Xu, BHC Components Ltd (KEMET), Electrochemical Studies for Aluminium Electrolytic Capacitor Applications: Corrosion Analysis of Aluminium in Ethylene Glycol-Based Electrolytes

- J.L. Stevens, T. R. Marshall, A.C. Geiculescu m, C.R. Feger, T.F. Strange, Carts USA 2006, The Effects of Electrolyte Composition on the Deformation Characteristics of Wet Aluminium ICD Capacitors, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bernard, Walter J; Randall Jr, John J (7 April 1961). "The Reaction between Anodic Aluminium Oxide and Water" (PDF). Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 154 (7): 355–361. doi:10.1149/1.2428230. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2014.

- "Alu Encyclopaedia, oxide layer". Aluinfo.de. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- J. M. Sanz, J. M. Albella, J. M. Martinez-Duart, On the inhibition of the reaction between anodic aluminium oxide and water

- Hillman, Craig; Helmold, Norman (2004), Identification of Missing or Insufficient Electrolyte Constituents in Failed Aluminium Electrolytic Capacitors (PDF), DFR solutions

- K. H. Thiesbürger: Der Elektrolyt-Kondensator 4th edition, Page 88 to 91, Roederstein, Landshut 1991 (OCLC 313492506)

- H. Kaesche, Die Korrosion der Metalle - Physikalisch-chemische Prinzipien und aktuelle Probleme, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1966, ISBN 978-3-540-51569-2 (1990 edition)

- "Ncc, Ecc". Chemi-con.co.jp. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "Nichicon". Nichicon-us.com. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "Elna". Elna. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Low-ESR Aluminium Electrolytic Failures Linked to Taiwanese Raw Material Problems (PDF), Molalla, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012

- Chang, Jeng-Kuei, Liao, Chi-Min, Chen, Chih-Hsiung, Tsai, Wen-Ta, Effect of electrolyte composition on hydration resistance of anodized aluminium oxide

Further reading

- H. Kaesche, Die Korrosion der Metalle - Physikalisch-chemische Prinzipien und aktuelle Probleme, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2011, ISBN 978-3-642-18427-7

- C. Vargel, Corrosion of Aluminium, 1st Edition, 2 October 2004, Elsevier Science, Print Book ISBN 978-0-08-044495-6, eBook ISBN 978-0-08-047236-2

- W. J. Bernard, J. J. Randall Jr., The Reaction between Anodic Aluminium Oxide and Water, 1961 ECS - The Electrochemical Society

- Ch. Vargel, M. Jacques, M. P. Schmidt, Corrosion of Aluminium, 2004 Elsevier B.V., ISBN 978-0-08-044495-6

- Patnaik, P. (2002). Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049439-8.

- Wiberg, E. and Holleman, A. F. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-352651-5