Carrier-grade NAT

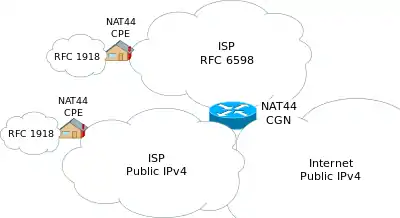

Carrier-grade NAT (CGN or CGNAT), also known as large-scale NAT (LSN), is an approach to IPv4 network design in which end sites, in particular residential networks, are configured with private network addresses that are translated to public IPv4 addresses by middlebox network address translator devices embedded in the network operator's network, permitting the sharing of small pools of public addresses among many end sites. This shifts the NAT function and configuration thereof from the customer premises to the Internet service provider network.

Carrier-grade NAT has been proposed as an approach for mitigating IPv4 address exhaustion.[1]

One use scenario of CGN has been labeled as NAT444,[2] because some customer connections to Internet services on the public Internet would pass through three different IPv4 addressing domains: the customer's own private network, the carrier's private network and the public Internet.

Another CGN scenario is Dual-Stack Lite, in which the carrier's network uses IPv6 and thus only two IPv4 addressing domains are needed.

CGNAT(s) are often seen by mobile telecom providers and small scale WISPs.[3]

Shared address space

If an ISP deploys a CGN, and uses RFC 1918 address space to number customer gateways, the risk of address collision, and therefore routing failures, arises when the customer network already uses an RFC 1918 address space.

This prompted some ISPs to develop a policy within the American Registry for Internet Numbers (ARIN) to allocate new private address space for CGNs, but ARIN deferred to the IETF before implementing the policy indicating that the matter was not a typical allocation issue but a reservation of addresses for technical purposes (per RFC 2860).

IETF published RFC 6598, detailing a shared address space for use in ISP CGN deployments that can handle the same network prefixes occurring both on inbound and outbound interfaces. ARIN returned address space to the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) for this allocation.[4] The allocated address block is 100.64.0.0/10.[5]

Devices evaluating whether an IPv4 address is public must be updated to recognize the new address space. Allocating more private IPv4 address space for NAT devices might prolong the transition to IPv6.

Disadvantages

Critics of carrier-grade NAT argue the following aspects:

- Like any form of NAT, it breaks the end-to-end principle.[6]

- It has significant security, scalability, and reliability problems, by virtue of being stateful.

- It makes it impossible to host services.

- It does not solve the IPv4 address exhaustion problem when a public IP address is needed, such as in web hosting.

Carrier-grade NAT usually prevents the ISP customers from using port forwarding, because the network address translation (NAT) is usually implemented by mapping ports of the NAT devices in the network to other ports in the external interface. This is done so the router will be able to map the responses to the correct device; in carrier-grade NAT networks, even though the router at the consumer end might be configured for port forwarding, the "master router" of the ISP, which runs the CGN, will block this port forwarding because the actual port would not be the port configured by the consumer.[7] In order to overcome the former disadvantage, the Port Control Protocol (PCP) has been standardized in the RFC 6887.

In cases of banning traffic based on IP addresses, the system might block the traffic of a spamming user by banning the user's IP address. If that user happens to be behind carrier-grade NAT, other users sharing the same public address with the spammer will be mistakenly blocked.[7] This can create serious problems for forum and wiki administrators attempting to address disruptive actions from a single user sharing an IP address with legitimate users.

References

- S. Jiang; D. Guo; B. Carpenter (June 2011), An Incremental Carrier-Grade NAT (CGN) for IPv6 Transition, ISSN 2070-1721, RFC 6264

- "NAT444 (CGN/LSN) and What it Breaks".

- Doyle, Jeff (2009-09-04). "Understanding Carrier Grade NAT". Network World. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- "Re: shared address space... a reality!". Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- "100.64.0.0/10 – Shared Transition Space".

- "Assessing the Impact of NAT444 on Network Applications".

- http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/technology-research/2013/cgnat.pdf