Certificate of need

A certificate of need (CON), in the United States, is a legal document required in many states and some federal jurisdictions before proposed acquisitions, expansions, or creations of healthcare facilities are allowed. CONs are issued by a federal or state regulatory agency with authority over an area to affirm that the plan is required to fulfill the needs of a community.

History

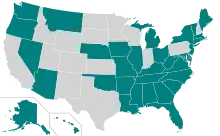

The concept of the CON first arose in the field of health care and was passed first in New York in 1964 and then into federal law during the Richard Nixon administration in 1974, with the passage of the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act.[1][2][3] Certificates of need are necessary for the construction of medical facilities in 35 states and are issued by state health care agencies:

The certificate-of-need requirement was originally based on state law. New York passed the first certificate-of-need law in 1964, the Metcalf–McCloskey Act. From that time to the passage of Section 1122 of the Social Security Act in 1972, another 18 states passed certificate-of-need legislation. Section 1122 was enacted because many states resisted any form of regulation dealing with health facilities and services.[4]

A number of factors spurred states to require CONs in the healthcare industry. Chief among these was the concern that the construction of excess hospital capacity would cause competitors in an oversaturated field to cover the costs of a diluted patient pool by overcharging, or by convincing patients to accept hospitalization unnecessarily.[5]

In some instances where state and federal authorities overlap, federal regulations may defer authority from the federal agency to the state agency with concurrent authority as to the issuance of a certificate of need. However, deferment of this authority is not required. For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD ) issued the following determination:

HUD conducts the same analysis of need whether or not the state has a CON process. There is wide variation in the methods CON states use to decide whether or not to issue a certificate. HUD believes that the Act's required need assessment is best performed using a method that is applied consistently to hospitals in all states. Should the state's CON process and HUD's assessment of need reach differing conclusions on the need for a proposed project, HUD will review the case closely to determine if its conclusion should be changed.[6]

CONs are sometimes sold in bankruptcy as an asset,[7] and the CON requirement is sometimes used by competitors to block the reopening of existing hospitals.[8]

Criticism

Since new hospitals cannot be constructed without proving a "need", the certificate-of-need system grants monopoly privileges to already existing hospitals. Consequently, Alaska House of Representatives member Bob Lynn has argued that the true motivation behind certificate-of-need legislation is that "large hospitals are... trying to make money by eliminating competition" under the pretext of using monopoly profits to provide better patient care.[9] A 2011 study found that CONs "reduce the number of beds at the typical hospital by 12 percent, on average, and the number of hospitals per 100,000 persons by 48 percent. These reductions ultimately lead urban hospital CEOs in states with CON laws to extract economic rents of $91,000 annually".[10]

Michigan's certificate of need laws restricted the availability of CAR T-cell cancer therapy until the legislature intervened in 2019.[11][12] Some political advocacy organizations have blamed CONs for the shortage of hospital beds during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.[13]

References

- Certificate of Need Laws: A Prescription for Higher Costs, "In 1974, Congress passed a mandate for all states to establish a CON program as part of the National Health Planning and Resources Development Act."

- GEORGIA’S CERTIFICATE OF NEED (CON) PROGRAM, "Origin of CON • 1974: National Health Planning & Resource Development Act"

- Hyman, Herbert Harvey (1982). Health Planning: A Systematic Approach (2nd ed.). Aspen Publishers. p. 253. ISBN 0-89443-379-2. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- Cimasi, Robert James (2005). The U.S. healthcare certificate of need sourcebook. Washington, D.C.: Beard Books. p. 2. ISBN 9781587982750. OCLC 63110526.

- Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Housing – Federal Housing Commissioner, Federal Register, Vol. 72, No. 228 (72 FR 67524, 67531), issued November 28, 2007.

- Straight, Harry (1992-01-30). "ORMC VYING FOR DELTONA SPOT". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2019-05-02. Retrieved 2019-05-02.

- "North Jersey News and Information | NorthJersey.com".

- "Another Attempt to Eliminate "Certificate of Need"". Blogs by Rep Bob Lynn. 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- Eichmann, Traci L.; Santerre, Rexford E. (2011). "Do hospital chief executive officers extract rents from Certificate of Need laws?". Journal of Health Care Finance. 37 (4): 1–14. ISSN 1078-6767. PMID 21812351.

- "Michigan Senate rejects regulation over CAR-T cancer treatment". Modern Healthcare. 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- Tolliver, Sandy (2019-11-16). "Cancer therapy dispute highlights need to repeal CON laws". TheHill. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- "America Doesn't Have Enough Hospital Beds To Fight the Coronavirus. Protectionist Health Care Regulations Are One Reason Why". Reason.com. 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

Further reading

- Cimasi, Robert James (2005). The U.S. Healthcare Certificate of Need Sourcebook. Beard Books. ISBN 9781587982750. Retrieved 2015-02-28. – "A state-by-state analysis of the certificate of need statutes, regulations, case law, and key state health department personnel".