Christian Konrad Sprengel

Christian Konrad Sprengel (22 September 1750 – 7 April 1816) was a German naturalist, theologist, and teacher. He is most famous for his research on plant sexuality. Sprengel was the first to recognize that the function of flowers was to attract insects, and that nature favoured cross-pollination. Along with the work of Joseph Gottlieb Kölreuter he set the foundations for the modern study of floral biology and anthecology although his work was not widely recognized until Charles Darwin examined and reconfirmed several of his observations.

Christian Konrad Sprengel | |

|---|---|

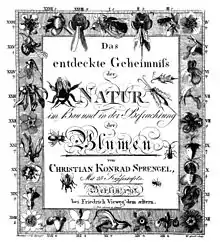

Cover page of Sprengel's landmark book (1793) | |

| Born | 22 September 1750 |

| Died | 7 April 1816 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Halle-Wittenberg |

| Known for | plant sexuality |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | natural history |

Life

Sprengel was born in Brandenburg an der Havel in the Margraviate of Brandenburg. He was the 15th and the last son of a preacher Ernst Victor Sprengel and his second wife Dorothea Gnadenreich Schaeffer (died 1778). Ernst Victor's father was an organist and he himself was a choir-master, teacher and later archdeacon. Christian Konrad was also expected to continue in the same profession and he studied theology in Halle. In 1774 he became a teacher in Berlin. In 1780 he moved to Spandau to head the Great Lutheran Town School. His interest in plants began around the age of 30 when he was advised by his surgeon to spend as much time outdoors as possible to avoid irritation of the eyes. The surgeon was Ernst Ludwig Heim, an amateur mycologist and botanist who also influenced Alexander von Humboldt. Sprengel looked around at plants and collaborated with Carl Ludwig Willdenow on his Florae Berolinensis Prodromus (1787). Sprengel did considerable research on the pollination of plants and the interaction between flowers and their insect visitors in what was later called a pollination syndrome. With his work Das entdeckte Geheimnis der Natur im Bau und in der Befruchtung der Blumen (Berlin 1793), he was one of the founders of pollination ecology and floral biology as a scientific discipline. Together with one of his predecessors, Josef G. Köhlreuter, he is still the classic author in this field. While conducting his researches on plants, Sprengel appears to have neglected management of the school, which mainly served the rich and powerful. Sprengel was accused of mistreating some of the students. He was accused of punishing a mayor's son by making him stand in class and hitting him with a stick leading to injury. A nine-year-old son of a councillor was beaten up as also were several other children. Sprengel was ultimately dismissed from service in 1784.[1][2]

Sprengel subsequently lived on a pension and took people out on botanical trips and wrote another book on the usefulness of bees in 1811. He suggested that bee-hives be placed close to fields to enhance their yield. Towards the end of his life he returned to studying classical literature and published his last book on Roman Poets with his comments in 1815. He died on 7 April 1816 and is buried at the Invalidenfriedhof in Berlin. There is no grave and no portrait of him exists.[1]

The secret of nature discovered in the structure and pollination of flowers

During Sprengel's time and even according to Joseph Gottlieb Kölreuter, insects were only accidental visitors to flowers. They were seen as thieves of nectar which was considered as a fluid meant to nourish the growing seed. It was believed that the flower was the place for the marriage of the male and female parts but it was generally believed that self-fertilization was the norm. Fertilization was understood by Kolreuter and he referred to pollen as farina fecundens (the "fertilizing flour"). Both Kolreuter and Sprengel believed in intelligent creation and used teleological explanations. Like John Ray, Sprengel too believed that the observation of nature was a kind of church service by beholding what "the wise Creator of nature had produced".[1]

Sprengel began his botanical explorations in 1787. That summer he noticed that the wood cranesbill (Geranium sylvaticum) had soft hairs on the lower part of the petals. He decided that they played a role and came up with the idea that they protected the nectar from rain in the same way that eyebrows and eyelashes prevented sweat from entering the eye. He collaborated with Willdenow and described Silene chlorantha (Willd.) Ehrh. (Caryophyllaceae) which is extremely rare in Berlin district. It took six years before Sprengel actually published his works. The book was based on the studies of 461 plants and included 25 copperplate engravings based on his own drawings.[1]

Sprengel identified that flowers were essentially organs designed to attract insects that aided in pollination. He observed that nectar was an attractant and that the petals had markings that guided insects to the nectar. He also observed dichogamy, both protogyny and protrandry and pointed out that this helped prevent self-pollination. He also noticed self-incompatibility. He classified insects as generalists and specialists and identified the principle of buzz pollination in Leucojum. He noticed that some flowers were nectarless, especially those that were wind-pollinated. He also observed that some flowers such as orchids attracted insects but did not have nectar but he did not fully understand the nature of the deception. He also recognized nectar theft by certain insects.[1]

During his lifetime, his work was somewhat neglected, not only because it seemed to a lot of his contemporaries as obscene that flowers had something to do with sexual functions, but also because the immanent importance of his findings on the aspects of selection and evolution was not recognized. One contemporary A. W. Henschel in Breslau (1820) wrote that Sprengel's idea gave the impression of a fairy tale to entertain a schoolboy. It did get a favourable review from his doctor Heim who wrote that the "work is a masterpiece, an original of which all of Germany can be proud" of. The director of Botanical Garden in Göttingen Georg Franz Hoffmann also noted that he had verified some of the observations. Charles Darwin was introduced to Sprengel's book by Robert Brown. Darwin recognized Sprengel and noted that "he clearly proved by innumerable observations how essential a part insects play in the fertilization of many plants. But he was in advance of his age." Darwin was impressed by Sprengel's approach and it inspired him in his own studies that led to the On the various contrivances by which British and foreign orchids are fertilised by insects, and on the good effects of intercrossing (1862) where he came up with the conclusion that nature abhors perpetual self-fertilization.[2]

Impact and subsequent work

Pollination was studied further by Federico Delpino who coined various terms for the modes and means by which it occurred.[3] Important modern successors like Paul Knuth, Fritz Knoll and Hans Kugler were inspired by Sprengel and brought great advances to the field of pollination ecology and floral biology. After the second World War, their work was continued by Stefan Vogel, Knut Faegri, Leendert van der Pijl, Amots Dafni, G. Ledyard Stebbins as well as Herbert Baker and Irene Baker.[1]

James Edward Smith named a genus of Epacridaceae in Sprengel's honour as Sprengelia. Kurt Sprengel, a nephew who also wrote on the history of medicine, was nominated to the "Regensburgische Botanische Gesellschaft".[1]

References

- Vogel, S. (1996). "Christian Konrad Sprengel's Theory of the Flower: The Cradle of Floral Ecology". In Lloyd, D. G.; Barret, S. C. H. (eds.). Floral Biology: Studies on Floral Evolution in animal-Pollinated Plants. New York.: Chapman & Hall. pp. 44–62.

- Zepernick, Bernhard; Meretz, Wolfgang (2001). "Christian Konrad Sprengel's Life in Relation to His Family and His Time. On the Occasion of His 250th Birthday". Willdenowia. 31 (1): 141–152. doi:10.3372/wi.31.31113. JSTOR 3997346. S2CID 86832559.

- Aliotta, G.; Aliotta, A. (2004). "Federico Delpino's scientific thought and the birth of modern biology in Europe" (PDF). Delpinoa. 46: 85–93.

- IPNI. C.K.Spreng.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christian Konrad Sprengel. |