Church of Our Lady of the Assumption, Villamelendro de Valdavia

The Church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción is a temple of worship under the Catholic Church and predominantly designed with a baroque style located in Villamelendro de Valdavia, belonging to the municipality of Villasila de Valdavia, in the province of Palencia, under the autonomous community of Castilla y León, Spain.

| Church of Our Lady of the Assumption | |

|---|---|

Interior | |

| |

| Location | Villamelendro de Valdavia |

| Country | Spain |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| History | |

| Status | Active |

| Dedication | Assumption of Mary and Saint Rocco |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Parish church |

| Architect(s) | Juan de la Cuesta |

| Style | Barroque architecture |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Palencia |

History

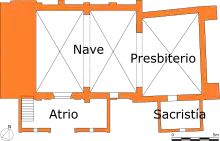

The Fuero de Villasila y Villamelendro granted by Alfonso VIII in 1180 attests to the existence of both towns since at least the 12th century, with the priests of both parishes coming to Carrión to request this privilege. The design of this church is built on top of a previous, more simple one. In fact, two different axes of symmetry can be seen. The part of the presbytery presents a slightly different alignment from the rest of the nave, so it can be deduced, being closer to the village, that this is the oldest part over which the rest of the building was enlarged.

On 21 February 1527, during the general chapter of the Order of Santiago, which took place in Valladolid, and which was presided over by Carlos I of Spain, the examination of the books of the visitation carried out in Old Castile by Lope Sánchez Becerra and Juan Alonso, a priest of Montemolín, was begun. Among them are those relating to the Hospital de las Tiendas and of Villamartin, referring to the fact that each half box marco must be paid for in silver (each Castilian marco weighed 230 g, so that the boxes that were manufactured should weigh 115grs each one) for the Church tabernacle, with destiny to Villasila and Villamelendro, as well as to find out if the rights that the Order could have had on an old well, lands and houses, are still in force.[1]

As a result of the 1549 pastoral visit to the church of Santa María de Villamelendro, documentation was left about the works that were being carried out at that time[2] where the work of the Cantabrian master stonemason is accredited Juan de la Cuesta[3] natural from Secadura, in the church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, which is the bulk of the current church building.

It is also known that during these works, Juan de la Cuesta collaborated with Pedro de Argadero, a neighbor of Carrión de los Condes in the execution of the same, the latter being in charge of making the wooden structure over the vaults on which the roof rests, since the visitor read a knowledge that Juan de la Cuesta de Pedro de Argadero, a neighbor of Carrión, was making the body of the temple.[4]

There are also other, later construction phases. Both the portico and its paving, as well as a later revision of the buttresses and sacristy, seem to respond to works that took place after the Juan de la Cuesta factory.

In 1771, Manuel Jacinto de Bringas, mayor of the province of Toro, created a file for the Count of Aranda detailing the state of the congregations, confraternities and brotherhoods in the towns of this jurisdiction. Villasila and Villamelendro are included in this report, with 4 Brotherhoods, 6 Guardianships and 6493 reales de vellón provided for these celebrations as both sacred and profane expenses.

Description

Outside

The church is made of brick, masonry and stonework, with a modern belfry tower at the foot made of plastered brick. It replaced the old masonry and brick tower with a hipped roof and two loopholes in the mid-20th century, as it threatened ruin.

There's a gate with a brick semicircular arch on the Epistle side. This is preceded by a portico with an access door with lowered arch flanked on the left and right with openings, lintels to sardinel. Although originally they would have been open, they were blinded after their construction, perhaps to protect the parishioners who congregated in the atrium from the cold.

The space of the portico behind the opening on the right was used as liturgical storage from some time after its erection until its restoration in 2012, when this storage was amortized. These works were focused on the recovery of the portico roof, cleaning of the interior facade and replacement of the adobe wall of the East enclosure by a thermo-clay wall. During the foundation of this wall, remains of skulls from bodies buried outside the church were found.

From that moment on, the atrium recovers the original space, except for the vanos that are glazed, bringing the original clarity to the interior, but offering protection from the atmospheric elements. When cleaning the floor of the space freed up by this storage area, it was found that the stones perceptible in the area of the doorway also continued towards this side of the portico. This is another record with 6 arms similar to that of the entrance. A motif repeated in so many church entrances in the area and which could correspond to some kind of protective sun symbol at the time of the entrance to the temple.

An ashlar also appeared, reused as a footing for a buttress of reinforcement after the work of Juan de la Cuesta, with a series of grooves that after the analysis of the experts of the Fundación de Santa María la Real of Aguilar de Campóo, determined that it was a Renaissance moulding reused at a later time than the main work. The grooves, 15 in all, are finished off with a semicircle at the top, and between the grooves there seems to be a kind of rope column.

In 2014, the gate, which was damaged by these works to refurbish the atrium, was restored by removing several layers of paint that had accumulated over the centuries. At least 4 shades were found, from grey, through light green, to light brown and finally dark brown. In the process of restoration, two more crosses were found to have been kicked, carved on the outside of the left door. A nail from the Ferrería de El Pobal in Muskiz was also used, as well as two other restored nails from local constructions that show a four-lobed exterior.

Outside, we should also point out the relief of a cruz patada, on one of the ashlars of the sacristy. This motif of a kicked cross is repeated on several doorways in the Palencia and Burgundy areas, with the cross almost always in the same position to the right of the main door. This custom could be associated with some kind of protective ritual already within the nineteenth century, probably the epidemic of cholera of 1855. Another possibility is that this relief was related to the Brotherhood of the Vera Cruz of Villamelendro. Each parish had at least two confraternities: one was the Vera Cruz Confraternity and the other the Animas Confraternity, which would explain their generic presence in other parishes.

Oral tradition tells how in the 1970s, during the excavation of a well in the corner of the land near the sacristy, a tombstone with characters appeared, currently in an unknown location.

On the outside of the apse, centred on the top, there is an eroded brick which local popular tradition calls the red saint due to the reddish colour of the material with which it was built. This served as a sundial during the summer season, and the shadow of the temple reaches this brick during the months of the heat wave, just as it arrives at noon, serving as a reference for the neighbors who were working in the vicinity of the temple.

The cemetery is located on the north side of the church. Originally it must have been built at the beginning of the 19th century, although the current one is an extended version of the original one and has access and walls that were remodelled by the Villasila Town Hall at the end of the 20th century.

Interior

The interior consists of a single nave, separated by arches of ashlars in three bodies covered with bóveda en arista and a high wooden choir at the feet. On the side of the presbytery is the main altarpiece from the first half of the 17th century with paintings on the bench of the Annunciation and Adoration of the Shepherds, flanked by four small panels representing the Fathers of the Church, from left to right: St Augustine of Hippo, St Gregory the Great, St Ambrose of Milan and St Jerome of Stridon on which four columns Corinthian Order are supported as an allegory for the pillars of the Church. The altarpiece is articulated around a central niche with the image of Asunción presiding and in the side streets four panels with paintings of the life and martyrdom of Julita y Quirico and in the attic Crucifix. Tabernacle with relief of the Resurrection on the door.

On the epistle side, rococo altarpiece (not gilded) with relief of the Souls and the Holy Trinity. On the Gospel side, there is a crucifix and altarpiece rococo identical to the one on the Epistle side but with gilded reliefs.

In the Baptistery, under the choir, there is a baptismal font with a large ribbon and with a relief of a cross kicked on one of its sides. By analogy with the font of the nearby Church of San Pelayo in Villasila de Valdavia, we could date it to the end of the 18th century.

At the same time, other more modern works of lesser artistic interest are kept, most notably a Sacred Heart of Jesus that was offered by the family of Martín Cabezón at the beginning of the 20th century for the safe return of their son Marcos Cabezón from the Third Carlist War.

In 1987 frescoes dating from the 18th century were discovered, on the gospel side a star motif is repeated on the floor of the church entrance. While on the epistle side the figure of an allegorical vase representing the Virgin Mary.[5]

The floor of the church, except for the part of the presbytery which is from the 20th century, is the original one made of terracotta tiles. Already from the end of the 18th century the need for burials to take place outside the church was promulgated, but it was not until later in the 19th century that the order was carried out. This is why many of the tiles are dented and have marks on the ends from being lifted and re-laid. The burials inside the Church were done by zones and could be paid for. That is why the wealthy chose areas as close as possible to the main altar and the poorer ones far from it.

Until the end of the 1980s, men sat in the choir, in the pews below the choir (where a still existing indigo blue and black bench, known as the pew of darkness, stood out) and the area closest to the entrance, while women sat in kneeling pews closest to the presbytery. These kneeling places were usually above the areas where their relatives were buried, and the place where the women of the same family sat from generation to generation remained.

There are two large banners. One of them is typical of holidays, with three bands of the same size, where the first and third are crimson and the middle one is white with the cross of Santiago in the middle, also crimson. The other is purple, with gold trimmings, to preside over the burials and moments of the Passion. Both banners are accompanied by a bronze processional cross and two deciochesque lanterns.

Conservation

Juan de la Cuesta's work presented problems from early times. It was necessary to reinforce the building with period buttresses so that they would reinforce the pressures that the groin vaults projected outwards. In the area of the apse it is reinforced with very thick but low buttresses, since in this area the church tends to open up as well. In the cemetery area, the base of these buttresses are eroded by humidity and burials, leaving the building unprotected.

That is why in the mid-20th century the arch of the presbytery was reinforced with a double tensor that gave it stability. The second arch of the nave, however, is increasingly giving way inwards, endangering the integrity of the second vault. In addition, at the end of the 20th century, the base of the whole church was painted with plastic paint, favouring that the humidity goes up the walls, weakening the integrity of the walls. This is the reason why this building is included in the Red Heritage List[6] of the Association for the care and promotion of Heritage Hispania Nostra since November 2019.

References

- García Rodríguez, Emilio, The General Chapter of the Military Order of Santiago of the year 1527 (PDF), p. 79,

El día 21 de febrero de 1527 se inicia el examen de los libros de las visitaciones realizadas en Castilla la Vieja por Lope Sánchez Becerra y Juan Alonso, sacerdote de Montemolín, tomándose los acuerdos que a continuación se expresan:..Hospital de las Tiendas de Villamartín. Someter a la resolución del Consejo la conveniencia de que, para evitar la duplicidad de capellanes existentes, uno de ellos fuese alemán, con dominio del francés, para servir de interprete, confesando a los peregrinos el administrador del establecimiento; costear sendas cajas de medio marco de plata para el Santísimo Sacramento, con destino a las Iglesias de Villasila y Villamelendro, e inquirir los derechos que pueda tener la Orden sobre un pozo antiguo, tierras y casas...

- "Los maestros canteros del Valle de Aras en Palencia". www.juntadevoto.com. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- uvadoc.uva.es/bitstream/10324/3026/1/TESIS349-130613.pdf

- Zalama, Miguel Ángel (1990), 16th century architecture in the province of Palencia, Diputación Provincial de Palencia, p. 260,

En el año 1549, en la Visita pastoral a la iglesia de Santa María de Villamelendro, el visitador leyó un conocimiento que tenía Juan de la Cuesta de Pedro de Argadero, carpintero vecino de Carrión, que estaba haciendo el cuerpo del templo.

- Trens, Manuel (1947). "Mary. Iconography of the Virgin in the Spanish art". worldcat.org. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción". Lista Roja del Patrimonio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2019-10-29. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

Bibliography

- Narganes Quijano, Faustino; González Díez, Emiliano (2004), A short history in the middle course of Valdavia: Villabasta, Villaeles, Arenillas de Nuño Pérez, Villasila and Villamelendro, City Hall of Villabasta, ISBN 84-606-3616-X

- Alcalde Crespo, Gonzalo (1999), La Vega, Loma y Valdavia: (Saldaña-Valdavia), Palencia: Cálamo, ISBN 84-95018-18-7