Citizens Building (Cleveland, Ohio)

The Citizens Building is a high-rise office and retail building located at 840 Euclid Avenue in Cleveland, Ohio, in the United States. The structure was built in 1903 by the Citizens Savings and Trust, a local bank. Its entrance portico was removed in 1924, and a two-story addition erected in its place. Home to the City Club of Cleveland since 1982, the building was renamed the City Club Building in 1999.

| City Club Building | |

|---|---|

The City Club Building in 1905 | |

| |

| Former names | Citizens Building |

| General information | |

| Status | Complete |

| Type | Office and retail |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| Location | 850 Euclid Avenue |

| Town or city | Cleveland, Ohio |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 41°30′0″N 81°41′13.56″W |

| Construction started | April 1, 1901 |

| Opened | September 28, 1903 |

| Renovated | March 1924 |

| Cost | $450,000 ($13,800,000 in 2019 dollars) |

| Client | Citizens Savings and Trust |

| Height | 177 feet (54 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 14 (1 below-ground) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Hubbell & Benes |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect | Harry D. Hughes |

Construction

Start of the project

In September 1899, Citizens Savings and Trust purchased a lot and two-story building located at 850 Euclid Avenue in Cleveland, Ohio. The property was owned by the city of Cleveland, which had purchased it in 1854.[1] The structure had originally been a high school, although more recently the first floor had served as the headquarters of the Cleveland public schools and second as the main branch of the Cleveland Public Library.[2] Citizens purchased the land and building at auction for $310,000.[1] Five months later, Citizens announced the selection of the local architectural firm of Hubbell & Benes as the architect of their new headquarters building. Hubbell & Benes proposed a 13-story, steel frame structure whose lower floors would be clad in granite and the upper floors in either brick or terra cotta.[3]

By summer 1900, plans for the new building were complete. It was planned for 14 stories (177 feet (54 m)),[4] which included a below-ground level.[5] The building was to have a frontage on Euclid Avenue of 104 feet (32 m)[6] and 197 feet (60 m) on Oak Street (now E. 8th Street). In addition to the main entrance on Euclid Avenue, there was a secondary entrance on Oak. The facade of the first two floors would be clad in Barre Granite, with the upper floors in brick and ivory colored, glazed terra cotta. A granite portico supported by four Doric columns,[4] each 30 feet (9.1 m) high and 4 feet 8 inches (1.42 m) in diameter,[6] masked the Euclid Avenue entrance. On the left (east) of the bank entrance was a door leading to a foyer and access to the offices on the third through thirteenth floors. This was balanced visually by the addition of a double window to the right (west).[4][lower-alpha 1] The main entrance led into a lobby 28 feet (8.5 m) wide and 47 feet (14 m) deep, with a skylight overhead providing natural light.[4] The lobby led to the main banking room, which was 190 feet (58 m) deep and 50 feet (15 m) high.[6][lower-alpha 2] To the right (west) of the lobby was the a women's banking parlor; to the left (east), a foyer which provided elevator and staircase access to the upper floors. Paralleling the main banking room on the east and west were separate halls, each 28 feet (8.5 m) wide and 50 feet (15 m) deep. On the left (east) was the safe deposit banking parlor, with the vault containing the safe deposit boxes located at the rear (south). On the right (west) was the bank's clerical department.[4] Initial estimates of the cost of construction were $1.2 to $1.5 million ($36,900,000 to $46,100,000 in 2019 dollars).[6]

Hubbell & Benes also designed the decorative interior scheme of the building.[5] The public hallways on every floor of the building had marble floors and walls. Muralist Edwin Blashfield, muralist Kenyon Cox, and Tiffany & Co. were commissioned to do work for the lobby.[4] McNulty Brothers of Chicago designed and executed the ornamental plaster,[7] Henry Watterson, a local carpenter, oversaw both the industrial and ornamental woodwork.[8]

Construction issues

By April 1901, the cost of the new Citizens Building had come down to just $450,000 ($13,800,000 in 2019 dollars).[9] Variety Iron Works of Cleveland was hired to erect the steel frame of the building,[10] and razing of the existing structure was scheduled to begin April 1, 1901.[11]

In the late fall of 1901, a major dispute occurred between Citizens Savings and architect Levi Scofield, who was erecting the Schofield Building on the property adjacent to the east side of the new bank high-rise.[12] Citizens and Scofield reached an agreement in which their two buildings would share a wall. Unlike the Citizens Building, which had a portico and small plaza in front of it, the Schofield Building extended all the way north to the property line, an additional 17 feet (5.2 m). The bank did not want Scofield to build a plain brick wall next to their elaborately decorated new building, so the two sides signed an agreement in which Scofield agreed to build a wall at least 21 inches (530 mm) thick.[13] To accommodate the thick wall, the bank allowed Scofield to encroach onto their property by 10.5 inches (270 mm). Scofield also agreed to adorn his wall with pilasters (ornamental columns). The agreement required that the base of the pilasters extend outward from the wall by at least 2.5 inches (64 mm).[14]

Scofield built the wall and pilasters, but the bank discovered that they extended onto the bank's land by more than the allowed 10.5 inches (270 mm). The bank sued. Scofield tore down his wall, and rebuilt it. This time, he embedded the pilasters into the wall like bas-relief. Once more the bank sued, arguing the base of the pilasters did not extend the required 2.5 inches (64 mm) from the wall, and again Scofield tore down the wall. The bank offered to allow Scofield to build a thinner wall, but Scofield said this would be a structural danger to his building. The written agreement the two sides had signed was in conflict in several places, and the parties turned to the local Court of Common Pleas to resolve their dispute.[13]

Despite several attempts to reach an out-of-court settlement and a visual inspection of the partially-completed Citizens Building,[15] the court was unable to find any law or precedent with which to guide its decision. On January 10, 1902, Scofield's engineering staff pointed out that an iron column at the northeast corner of the Citizens Building jutted into the space for Scofield's wall. The court suggested a compromise: Rather than have Scofield's brickworkers chip bricks to fit around the column (at significant cost and time), Citizens Savings would allow the Schofield Building to encroach slightly into the space allotted for the shared wall, but no more than needed to accommodate a single brick's width. This would allow Scofield to accommodate the jutting column into his wall. In return, Scofield would move his non-shared wall back 4 inches (100 mm), and enlarge his pilasters so they more closely mimicked those on the front of the Citizens Building. The two sides swiftly agreed to the compromise to avoid a ruling by the court which neither party would be happy with.[14]

Construction completion

The time-consuming dispute with Scofield disrupted the construction scheduled for the Citizens Building. With Citizen Savings forced to vacate its existing building (which was due to be razed), the bank was forced to occupy temporary quarters beginning February 3, 1902.[16]

Although the Citizens Building was not fully completed,[17] the structure opened to the public on September 28, 1903.[5] On opening day, the bank was open from 7 AM to 7:30 PM to accommodate the several hundred people who thronged the building to see its luxurious interior.[17] The safe deposit boxes and vaults were completed at the end of October 1903. More than $1 million in bonds, fur clothing, rugs, household silver, stocks, and other items were moved to the new bank.[18]

About the building

As completed, the Citizens Building consisted of 14 floors,[19] 13 above-ground and one below-ground.[20] The base of the edifice was rectangular, but from the third floor upward the structure was a U-shape (facing north).[19][lower-alpha 3] The shape meant that no interior office was more than 10 feet (3.0 m) from natural light.[19] The building's frame was made of steel,[19] with reinforced concrete floors. A new design, in which steel T-beams were embedded cross-down in the concrete, was used for the floors. This saved weight and expense, and yet was stronger than using I-beams.[23]

The Citizens Building was Renaissance Revival in style, with the exception of its Neoclassical portico.[24] This mixed design was somewhat controversial among architects.[19] The facade of the first two floors was granite. The third through eleventh floors were clad in brick, with ivory colored, glazed terra cotta around the windows. The two uppermost floors were completely clad in ivory-glazed terra cotta.[4]

The portico

The design of the entrance portico purposefully mimicked the Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens in Greece.[19] The portico was set back from the Euclid Avenue (north) property line by 17 feet (5.2 m).[25]

The portico consisted of four columns with Doric capitals. Each of the columns was 30 feet (9.1 m) high and 4 feet 8 inches (1.42 m) in diameter,[6] and made from a single piece of granite.[24] The tympanum supported by the columns was designed and sculpted by Joseph Carabelli, a prominent granite sculptor in Cleveland.[26] Like the columns, the tympanum was carved from a single piece of granite.[24] Sources differ as to the subject matter portrayed. One description said the work depicted an allegorical figure of Industry, with other figures laying tributes at her feet.[26] Another description, however, said that the work showed an allegorical figure representing Banking, who received gold from figures representing the city's sources of wealth and distributed this gold to the poor and elderly.[5] A third source described the work as consisting of 12 figures representing Industry and Thrift.[27]

The portico masked the entrance to the main bank of the Citizens Savings and Trust. This was a double-door entrance somewhat larger in height and width than a normal door. The architrave (the area that outlined the door frame) was inlaid with glass in a motif designed and executed by Tiffany & Co.[24] The massive bronze doors themselves did not open inward or outward, but rather slid sideways into the walls.[27]

Left (east) of the portico was a door leading to a foyer which provided elevator and stairway access to the offices on the third through thirteenth floors. Right (west) of the portico was a set of double-windows that let natural light into the women's banking parlor.[4]

Lobby and lobby side rooms

The main bank entrance led to a lobby[4] 38 feet (12 m) wide and 50 feet (15 m) deep.[5] The lobby had a barrel vault ceiling of leaded came glasswork, which provided extensive natural light.[27] The lobby walls[27] and pilasters were clad in Italian marble.[5] The pilasters, architraves, door lintels, and pier above the door featured inlays and designs of colored glass, gold, and mother-of-pearl by Tiffany & Co.[5]

On the left (east) side of the lobby, a door led to the foyer entrance for the upper floors. This area featured the same white Italian marble walls and pilasters with Tiffany inlays.[24]

On the right (west) side of the lobby, a door led to the women's banking parlor. The walls of this room were covered with silk brocade tapestries. The walls and pilasters were inlaid with Tiffany-designed decorations in ivory and gold. The furniture, commissioned specifically for this room, was of mahogany and upholstered in green damask.[27]

A second door in the west side of the lobby led to an elevator and staircase that provided access to the second floor above, but the bank's offices and special departments were located.[4]

Blashfield and Cox murals

The lobby features two allegorical lunette murals, one by Edwin H. Blashfield on the left (east) and one by Kenyon Cox on the right (west).[27] The two artists knew one another well, having worked on projects for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and for the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., in 1896 and 1897. The two men worked in separate studios, but regularly compared notes while working on their commissions for the Citizens Building.[28]

Blashfield's mural, "The Uses of Wealth",[lower-alpha 4] depicted Wealth (a female figure clad in gold) seated on the right, a cornucopia overflowing with gold at her feet. In one hand, she holds a key ("Opportunity"), and in the other an olive branch ("Peace"). Scattered around her seat are a military helmet, shield, and sword, implying that wealth protects life and property. Standing behind Wealth is a muscular man ("Labor") in a blue workshirt, cap, and brown trousers. His forward hand rests on a shovel. On the opposite side of the mural are three figures depicting the arts and sciences: A male chemist wearing an apron, with a retort and other chemistry glassware; a kneeling female musician, flowers falling from her lap and holding a lyre; and a poet, clad in academic regalia, holding a scroll. In front of the arts and sciences is a nude cherub, the lit torch in its hand a symbol of opportunity. Hovering in the center of the mural is another cherub, swathed in flowing red robes, holding a tablet on which the title of the work is inscribed in Latin.[5]

Cox's mural, "The Sources of Wealth", depicted on its left side Prudence (a woman, clad a gold-embroidered gown and red velvet cape) seated in front of a small temple. Behind her is a beehive, the symbol of industry and saving. Before her is a nude cherub, holding a bridle (the allegory for self-control).[28] On the right side of the mural are three female figures representing sources of wealth: A nude fisherwoman, holding aloft a fish; a farmer, clad in a rough dress and apron and holding a scythe and sheaf of wheat; and a kneeling weaver in rich robes, unrolling a carpet.[30] Behind them are more symbols of industry, including an iron box and blacksmith's tongs. In the center of the mural floats a female representation of Commerce, greeting Prudence[30] and holding a caduceus. The caduceus is the staff carried by Hermes, god of commerce, in Greek mythology.[5] In some ways, Cox's mural resembled the lunette he created for the Library of Congress, but the Cleveland work was more subtle in its use of allegory and symbol.[31][lower-alpha 5]

Both works were highly praised by the press and other artists when they were unveiled in 1903. Modern critics consider them to be the epitome of early 20th century commercial propaganda.[30]

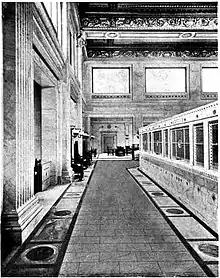

Main banking room and upper floors

As completed, the main banking room was 50 feet (15 m) wide and 110 feet (34 m) long. In the center of the room was a 70-foot (21 m) long, U-shaped counter. The closed end of the counter faced the lobby, and bank tellers worked from teller's cages in the center of the counter.[5] The counter was made of marble, and inlaid by Tiffany & Co. with smoked glass and mother-of-pearl. The teller's cages were designed by Hubbell & Benes, and executed by the Jno. Williams, Inc. foundry of New York City. The front of each cage was a bronze grille, adorned with bas-reliefs. The walls and pilasters of the main banking room were covered in Italian marble,[27] inlaid with glass and gold motifs designed and executed by Tiffany & Co. The ceiling was finished in silver and gold, which reflected the light from hundreds of small electric lamps. Between the pilasters near the cornice of the room were aphorisms about investment, saving, thrift, and other financial topics. These were depicted in glass mosaics, also designed by Tiffany & Co. At the south end of the main banking room was a large clock with illuminated numbers. Surrounding the cloak were more glass-mosaic aphorisms by Tiffany. All the lighting fixtures in the room were of bronze,[24] and all the furniture was mahogany, specially commissioned for the room.[27]

Paralleling the main banking room on the east and west were halls 28 feet (8.5 m) wide and 50 feet (15 m) deep. The east hall was the safe deposit banking parlor, with small and medium-sized safe deposit boxes located at the rear (south). The west hall contained the bank's clerical department.[4]

The public spaces in the basement and on the upper floors all had marble floors and marble wainscoting.[4] The bank's cash and large-item vaults were located in the basement. The second floor of the building was occupied by various offices and departments of Citizens Savings and Trust, such as offices for the president, treasurer, vice president, secretary, assistant secretaries, and assistant treasurers; meeting room of the board of directors; and the bank's trust and other departments.[5] All floors were accessible via electric elevators.[19] The building had its own electrical generating plant, air conditioning plant, and a water chilling plant that provided ice water on every floor. There was also a central vacuum cleaner system.[24]

1924 removal of the portico

The Union Trust Co. purchased the Citizens Building in August 1923 for $3 million ($45,000,000 in 2019 dollars).[33] The new owner removed the portico in March 1924.[34] The Blashfield mural was destroyed,[35] although the fate of the Cox mural and Carabelli tympanum are not known.

Local architect Harry D. Hughes designed a new addition which replaced the portico. It was 104 feet (32 m) in wide, and extended the building 17 feet (5.2 m) forward to the property line for a total depth of 110 feet (34 m). The one-story addition was 18 feet (5.5 m) in height, and designed to contain six retail stores in addition to an entrance foyer leading to the rear and the rest of the original structure. Hughes also oversaw the renovation of the main building's basement and removal of a mezzanine (which was replaced by a new second story). The total cost of the addition and renovations was $400,000 ($6,000,000 in 2019 dollars).[25]

Architectural historian Joseph J. Korom called the addition an "exercise in design banality".[19]

1999 renaming

In 1982, the City Club of Cleveland moved into new headquarters on the second floor of the Citizens Building.[36] In 1998, the City Club initiated a $1 million ($1,600,000 in 2019 dollars) capital fundraising campaign to renovate its part of the Citizens Building. The organization also agreed to renew its lease in the building for 10 years, with an option to renew for 20 more years. The building's owner, Barris-Guren & Co., agreed to rename the edifice after the City Club.[37][lower-alpha 6]

The renovation, which ended up costing $2.5 million ($3,800,000 in 2019 dollars) increased the auditorium's seating capacity by 5 percent, reconfigured the lobby into a much larger space, and installed advanced telecommunications and computer networking equipment. Large letters spelling "The City Club" were installed vertically on the E. 8th Street side of the structure at a cost of $30,000.[39] The remodeling and renaming was completed in January 2000.[40]

References

- Notes

- These windows let natural light into the women's parlor.[4]

- This was later changed to 146 feet (45 m) deep, 47 feet (14 m) wide, and 34 feet (10 m) high.[4]

- Hubbell & Benes would largely replicate this design in their Illuminating Building,[21] a 15-story office tower constructed on Cleveland's Public Square in 1915.[22]

- It was also known by the title "Capital, Supported by Labor, Offering the Golden Key of Opportunity to Science, Literature, and Art".[29]

- Cox received a gold medal for mural at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904.[32]

- Barris-Guren obtained a 50 percent interest in the Citizens Building in 1977.[38]

- Citations

- "Twelve Minutes To Make The Deal". The Plain Dealer. September 26, 1899. p. 3.

- "May Be Without A Home". The Plain Dealer. November 15, 1899. p. 10.

- "To Build A Skyscraper". The Plain Dealer. March 17, 1900. p. 10.

- "A Superb New Bank and Office Building". The Plain Dealer. July 1, 1900. p. 10.

- "Splendid New Banking Home". The Plain Dealer. September 27, 1903. p. 13.

- "A Magnificent Structure". The Plain Dealer. May 4, 1900. p. 8.

- "Builders' Gossip". The Plain Dealer. October 5, 1902. p. 16.

- "New Board of Directors of the Builders' Exchange". The Plain Dealer. November 16, 1902. p. 13.

- "Will Cost Nearly Half a Million". The Plain Dealer. April 24, 1901. p. 2; "Rush For Building Permits". The Plain Dealer. April 28, 1901. p. 16.

- "Lives of Workmen". The Plain Dealer. February 15, 1902. p. 3.

- "To Start Work". The Plain Dealer. March 26, 1901. p. 10.

- "War Over Party Wall In Court". The Plain Dealer. November 28, 1901. p. 2.

- "Party Wall Suit Is A Puzzler". The Plain Dealer. January 9, 1902. p. 9.

- "Save Chipping A Lot of Bricks". The Plain Dealer. January 11, 1902. p. 5.

- "Judge Climbed Skyscraper". The Plain Dealer. December 18, 1901. p. 4; "Fight Grows More Fierce". The Plain Dealer. December 31, 1901. p. 8; "Skyscrapers In Court". The Plain Dealer. January 1, 1902. p. 7.

- "Bank Will Move". The Plain Dealer. January 23, 1902. p. 4.

- "Bank In New Home". The Plain Dealer. September 29, 1903. p. 4.

- "To The New Vaults". The Plain Dealer. October 17, 1903. p. 10.

- Korom 2008, p. 259.

- Moody's Manual of Investments 1944, p. 703.

- Johannesen 1979, p. 124.

- Rose 1990, p. 719.

- Mensch, Leopold (March 1903). "The Hennebique System of Armored Concrete Construction—Part III". The National Builder. p. 18. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- Davies, William G. (July 1911). "Managing Buildings in Cleveland". Building Management. p. 50. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- "Front Addition for Citizens Building". The Plain Dealer. February 17, 1924. p. 8.

- "Cleveland News". The National Builder. February 1903. p. 23. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- "Citizens Savings and Trust Company, Cleveland, Ohio". American Art in Bronze and Iron. April 1910. p. 71. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- Morgan 1994, p. 151.

- Van Hook 2003, p. 34.

- Van Hook 2003, p. 115.

- Morgan 1994, p. 151, 153.

- Morgan 1994, p. 201.

- "Third Parcel Sold Near Euclid-E. 9th". The Plain Dealer. August 12, 1923. p. 10.

- Tugman, W.M. (March 28, 1924). "Offers City Pillars of Citizens Building". The Plain Dealer. pp. 1, 4.

- Van Hook 2003, p. 116.

- "Women's Club, City Club OK Move". The Plain Dealer. March 11, 1982. p. A10.

- Lubinger, Bill (July 12, 1998). "Send Money". The Plain Dealer. p. H2.

- Gleisser, Marcus (August 7, 1979). "$50 Million Office Twins Proposed on Euclid Ave". The Plain Dealer. pp. A1, A9; Gleisser, Marcus (August 12, 1979). "King-Sized Problems". The Plain Dealer. p. H35.

- Robinson, Alice (September 2, 1999). "New Look, New Lettering, Same Freedom". The Plain Dealer. p. B1.

- Lubinger, Bill (February 10, 2000). "Naming Rights Give Companies Cachet, Sweeter Building Leases". The Plain Dealer. p. C1.

Bibliography

- Johannesen, Eric (1979). Cleveland Architecture, 1876-1976. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society. ISBN 9780911704211.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Korom, Joseph J. (2008). The American Skyscraper, 1850-1940: A Celebration of Height. Boston: Branden Books. ISBN 9780828321884.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moody's Manual of Investments. New York: Moody's Investors Service. 1944.

- Morgan, H. Wayne (1994). Kenyon Cox: 1856-1919: A Life in American Art. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384858.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rose, William Ganson (1990). Cleveland: The Making of a City. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384285.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Hook, Bailey (2003). The Virgin and the Dynamo: Public Murals in American Architecture, 1893-1917. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821415016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to City Club Building. |