Cochinchina

Cochinchina (/ˈkoʊtʃɪnˌtʃaɪnə/; Vietnamese: Miền Nam; Khmer: កូសាំងស៊ីន, romanized: Kausangsin; French: Cochinchine; Chinese: 交趾支那) is a historical exonym for part of Vietnam, depending on the contexts. Sometimes it referred to the whole of Vietnam, but it was commonly used to refer to the region south of the Gianh River.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Vietnam was divided between the Trịnh lords to the north and the Nguyễn lords to the south. The two domains bordered each other on the Son–Gianh River. The northern section was called Tonkin by Europeans, and the southern part, Đàng Trong, was called Cochinchina by most Europeans and Quinam by the Dutch.[1]

Lower Cochinchina (Basse-Cochinchine) or Southern Vietnam, whose principal city is Saigon, is the newest territory of the Vietnamese people in the movement of Nam tiến (Southward expansion). This region was also the first part of Vietnam to be colonized by the French. Inaugurated as the French Cochinchina in 1862, this colonial administrative unit reached its full extent from 1867 and was a constituent territory of French Indochina from 1887 until early 1945. So during the French colonial period, the label "Cochinchina" moved further south, and came to refer exclusively to the southernmost part of Vietnam, once under the influence of Cambodia. Beside the French colony of Cochinchina, the two other parts of Vietnam at the time were the French protectorates of Annam (Central Vietnam) and Tonkin (Northern Vietnam). South Vietnam (also called Nam Việt) was reorganized from the State of Vietnam after the Geneva Conference in 1954 by combining Lower Cochinchina with the southern part of Annam, the former protectorate.

Background

The conquest of the south of present-day Vietnam was a long process of territorial acquisition by the Vietnamese. It is called Nam tiến (Chinese characters: 南進, English meaning "South[ern] Advance") by Vietnamese historians. Vietnam (then known as Đại Việt) greatly expanded its territory in 1470 under the great king Lê Thánh Tông, at the expense of Champa. The next two hundred years was a time of territorial consolidation and civil war with only gradual expansion southwards.[2]

In 1516, Portuguese traders sailing from Malacca landed in Da Nang, Đại Việt,[3] and established a presence there. They named the area "Cochin-China", borrowing the first part from the Malay Kuchi, which referred to all of Vietnam, and which in turn derived from the Chinese Jiāozhǐ, pronounced Giao Chỉ in Vietnam.[4] They appended the "China" specifier to distinguish the area from the city and the princely state of Cochin in India, their first headquarters in the Malabar Coast.[5][6]

As a result of a civil war that started in 1520, the Emperor of China sent a commission to study the political status of Annam in 1536. As a consequence of the delivered report, he declared war against the Mạc dynasty. The nominal ruler of the Mạc died at the very time that the Chinese armies passed the frontiers of the kingdom in 1537, and his father, Mạc Đăng Dung (the real power in any case), hurried to submit to the Imperial will, and declared himself to be a vassal of China. The Chinese declared that both the Lê dynasty and the Mạc had a right to part of the lands and so they recognised the Lê rule in the southern part of Vietnam while at the same time recognising the Mạc rule in the northern part, which was called Tunquin (i.e. Tonkin). This was to be a feudatory state of China under the government of the Mạc.

However, this arrangement did not last long. In 1592, Trịnh Tùng, leading the Royal (Trịnh) army, conquered nearly all of the Mạc territory and moved the Lê kings back to the original capital of Hanoi. The Mạc only held on to a tiny part of north Vietnam until 1667, when Trịnh Tạc conquered the last Mạc lands.

Cochinchina Kingdom of the Nguyen lords (1600–1774)

In 1600 after returning from Tonkin, lord Nguyễn Hoàng built his own government in the two southern provinces of Thuận Hóa and Quảng Nam, today in central Vietnam. In 1623, lord Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên established a trading community at Saigon, then called Prey Nakor, with the consent of the king of Cambodia, Chey Chettha II. Over the next 50 years, Vietnamese control slowly expanded in this area but only gradually as the Nguyễn were fighting a protracted civil war with the Trịnh lords in the north.

With the end of the war with the Trịnh, the Nguyễn were able to devote more effort (and military force) to conquest of the south. First, the remaining Champa territories were taken; next, the areas around the Mekong river were placed under Vietnamese control. At least three wars were fought between the Nguyễn lords and the Cambodian kings in the period 1715 to 1770 with the Vietnamese gaining more territory with each war. The wars all involved the much more powerful Siamese kings who fought on behalf of their vassals, the Cambodians.

During the late 18th century emerged the Tây Sơn Rebellion, coming out from the Nguyễn domain. In 1774, the Trịnh army captured the capital Phú Xuân of the Nguyễn realm, whose leaders then had to flee to Lower Cochinchina. The three brothers of Tây Sơn, former peasants, however, soon succeeded in conquering first the lands of the Nguyễn and then the lands of the Trịnh, briefly unifying Vietnam.

- Cochinchina Empire of the Nguyễn (1802–1862)

Final unification of Vietnam came under Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, a tenacious member of the Nguyễn noble family who fought for 25 years against the Tây Sơn and ultimately conquered the entire country in 1802. He ruled all of Vietnam under the name Gia Long. His son Minh Mạng reigned from 14 February 1820 until 20 January 1841 what was known to the British as Cochin China and to the Americans as hyphenated Cochin-China. In hopes of negotiating commercial treaties, the British in 1822 sent East India Company agent John Crawfurd,[7] and the Americans in 1833 sent diplomatist Edmund Roberts,[8] who returned in 1836.[9] Neither envoy was fully cognizant of conditions within the country, and neither succeeded.

Gia Long's successors (see the Nguyễn dynasty for details) repelled the Siamese from Cambodia and even annexed Phnom Penh and surrounding territory in the war between 1831 and 1834, but were forced to relinquish these conquests in the war between 1841 and 1845.

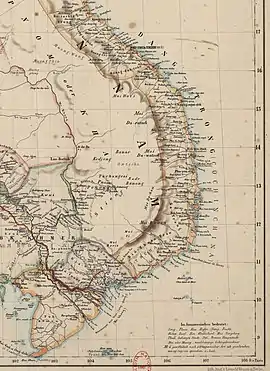

Cochinchina (light yellow) to the South.

Colonial Cochinchina: 1862–1945

Conquest and establishment

In 1858, under the pretext of protecting the work of French Catholic missionaries, which the Nguyễn dynasty increasingly regarded as a political threat, French Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly attacked Tourane (present day Da Nang) in Annam.[10] Early in 1859 he followed this up with an attack on Saigon, but as in Tourane was unable to seize territory outside of the defensive perimeter of the city. The Vietnamese Siege of Saigon was not lifted until 1861 when additional French forces were able to advance across the Mekong Delta.

The Vietnamese conceded in 1862 and signed the Treaty of Saigon. This ensured the free practice of the Catholic religion; opened the Mekong Delta (and three ports in the north, in Tonkin) to trade; and ceded to France the provinces of Biên Hòa, Gia Định and Định Tường along with the islands of Poulo Condore. In 1864 the three annexed provinces were formally constituted as the French colony of Cochinchina. In 1867, French Admiral Pierre de la Grandière forced the Vietnamese to surrender three additional provinces, Châu Đốc, Hà Tiên and Vĩnh Long. With these three additions all of southern Vietnam and the Mekong Delta fell under French control.[11]

In 1887, the colony of French Cochinchina became part of the Union of French Indochina, while remaining separated from the protectorates of Annam and Tonkin. So during the French colonial period, the label "Cochinchina" moved further south, and came to refer exclusively to the southern third of Vietnam. (In Catholic ecclesiastical contexts Cochinchina still related to the older meaning of Đàng Trong until 1924 when the three Apostolic Vicariates of Northern, Eastern, and Western Cochinchina were renamed to Apostolic Vicariates of Huế, Qui Nhơn, and Saïgon).

Plantation economy

The French authorities dispossessed Vietnamese landowners and peasants to ensure European control of the expansion of rice and rubber production.[12] The French began rubber production in Cochinchina in 1907 seeking a share of the monopoly profits that the British were earning from their plantations in Malaya. Investment from metropolitan France was encouraged by large land grants allowing for rubber cultivation on an industrial scale.[13] Virgin rainforests in eastern Cochinchina, the highly fertile 'red lands', were cleared for the new export crop.[14]

As they expanded in response to the increased rubber demand after the First World War, the European plantations recruited, as indentured labour, workers from "the overcrowded villages of the Red River Delta in Tonkin and the coastal lowlands of Annam".[15] These migrants, despite Sûreté efforts at political screening, brought south the influence of the Communist Party of Nguyen Ai Quoc (Ho Chi Minh),[16] and of other underground nationalist parties (the Tan Viet and Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng—VNQDD).[17] At the same time, the local peasantry were driven into debt servitude, and into plantation labour, by land and poll taxes.[18][19] This combination led to widespread and recurring unrest and to strikes. Of these the most significant, leading to armed confrontations, was the refusal of work by labourers Phu Rieng Do, a sprawling 5,500 hectares Michelin rubber plantation in 1930.[20]

In response to rural unrest and to growing labour militancy in Saigon, between 1930 and 1932 the French authorities detained more than 12,000 political prisoners, of whom 88 were guillotined, and almost 7000 sentenced to prison or to hard labour in penal colonies.[21]

Popular Front promise of reform

In 1936 the formation in France of the Popular Front government led by Leon Blum was accompanied by promises of colonial reform. In Cochinchina the new governor-general of Indochina Jules Brévié,[22] sought to defuse the tense and expectant political situation by amnestying political prisoners, and by easing restrictions on the press, political parties,[22] and trade unions.[23]

Saigon witnessed further unrest culminating in the summer of 1937 in general dock and transport strikes.[24] In April of that year the Communist Party and their Trotskyist left opposition ran a common slate for the municipal elections with both their respective leaders Nguyễn Văn Tạo and Tạ Thu Thâu winning seats. The exceptional anti-colonial unity of the left, however, was split by the lengthening shadow of the Moscow Trials and by growing protest over the failure of the Communist-supported Popular Front to deliver constitutional reform.[25] Colonial Minister Marius Moutet, a Socialist commented that he had sought "a wide consultation with all elements of the popular [will]," but with "Trotskyist-Communists intervening in the villages to menace and intimidate the peasant part of the population, taking all authority from the public officials," the necessary "formula" had not been found.[26]

War and the Insurrection of 1940

In April 1939 Cochinchina Council elections Tạ Thu Thâu led a "Workers' and Peasants' Slate" into victory over both the moderate Constitutionalists and the Communists' Democratic Front. Key to their success was popular opposition to the war taxes ("national defence levy") that the Communist Party, in the spirit of Franco-Soviet accord, had felt obliged to support.[27] Brévié set the election results aside and wrote to Colonial Minister Georges Mandel: "the Trotskyists under the leadership of Ta Thu Thau, want to take advantage of a possible war in order to win total liberation." The Stalinists, on the other hand, are "following the position of the Communist Party in France" and "will thus be loyal if war breaks out."[28]

With the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 23, 1939, the local Communists were ordered by Moscow to return to direct confrontation with the French. Under the slogan "Land to the Tillers, Freedom for the workers and independence for Vietnam",[29] in November 1940 the Party in Cochinchina instigated a widespread insurrection. The revolt did not penetrate Saigon (an attempted uprising in the city was quelled in a day). In the Mekong Delta fighting continued until the end of the year.[30][31]

The August Revolution and the return of the French

Cochinchina was occupied by Japan during World War II (1941–45). On September 2, 1945, in Hanoi Ho Chi Minh and his a new Front for the Independence of Vietnam, the Viet Minh, proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Already on August 24 the Viet Minh had declared a provisional government (a Southern Administrative Committee) in Saigon. When, for the declared purpose of disarming the Japanese, the Viet-Minh accommodated the landing and strategic positioning of their wartime "democratic allies", the British, rival political groups turned out in force including the syncretic Hoa Hao and Cao Dai sects. On September 7 and 8, 1945, in the delta city of Cần Thơ the Committee had to rely on what had been the Japanese-auxiliary, Jeunesse d'Avant-Garde/Thanh Nien Tienphong [Vanguard Youth]. They fired upon crowds demanding arms against the French.[32]

In Saigon, the violence of a French restoration assisted by British and surrendered Japanese troops, triggered a general uprising on September 23. In the course of what became known as the Southern Resistance War (Nam Bộ kháng chiến)[33] the Viet Minh defeated rival resistance forces but, by the end of 1945, had been pushed out of Saigon and major urban centres into the countryside.

After 1945, the status of Cochinchina was a subject of discord between France and Ho Chi Minh's Viet Minh. In 1946, the French proclaimed Cochinchina an "autonomous republic", which was one of the causes of the First Indochina War. In 1948, Cochinchina was renamed as the Provisional Government of Southern Vietnam. It was merged the next year with the Provisional Central Government of Vietnam, and the State of Vietnam, with former emperor Bảo Đại as head of state, was then officially established.

After the First Indochina War, Cochinchina was merged with southern Annam to form South Vietnam, which was later established as the Republic of Vietnam in 1955 by President Ngo Dinh Diem.

References

- Li, Tana (1998). Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. SEAP Publications. ISBN 9780877277224.

- Michael Arthur Aung-Thwin; Kenneth R. Hall (13 May 2011). New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia: Continuing Explorations. Routledge. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-1-136-81964-3.

- Li, Tana Li (1998). Nguyễn Cochinchina: southern Vietnam in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. SEAP Publications. p. 72. ISBN 0-87727-722-2.

- Reid, Anthony. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce. Vol 2: Expansion and Crisis. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. p211n.

- Yule, Sir Henry Yule, A. C. Burnell, William Crooke (1995). A glossary of colloquial Anglo-Indian words and phrases: Hobson-Jobson. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 0-7007-0321-7.

- Tana Li (1998). Nguyễn Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. SEAP Publications. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-0-87727-722-4.

- Crawfurd, John (21 August 2006) [1830]. Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-general of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. 475 pgs. OCLC 03452414. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Roberts, Edmund (1837) [First published in 1837]. Embassy to the Eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat : in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock ... during the years 1832-3-4 (Digital ed.). Harper & brothers (published 12 October 2007). 310 pages. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Ruschenberger, William Samuel Waithman (24 July 2007) [First published in 1837]. A Voyage Round the World: Including an Embassy to Muscat and Siam in 1835, 1836 and 1837. Harper & brothers. OCLC 12492287. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (1999). Vietnam. University Press of Kentucky. p. 29. ISBN 0-8131-0966-3 – via Internet Archive.

- Llewellyn, Jennifer; Jim Southey; Steve Thompson (2018). "Conquest and Colonisation of Vietnam". Alpha History. Alpha History. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Cleary, Mark (July 2003). "Land codes and the state in French Cochinchina c. 1900–1940". Journal of Historical Geography. 29 (3): 356–375. doi:10.1006/jhge.2002.0465.

- Murray. "'White Gold' or 'White Blood'?": 46. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Murray. "'White Gold' or 'White Blood'?": 47. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Murray. "'White Gold' or 'White Blood'?": 50. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Thomas. Violence and Colonial Order. p. 145.

- Van, Ngo (2010). In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary. Oakland CA: AK Press. p. 51. ISBN 9781849350136.

- Marr. Vietnamese Tradition on Trial. p. 5.

- Murray. "'White Gold' or 'White Blood'?": 51. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Marr. The Red Earth. p. x.

- Van, Ngo (2010). In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary. Oakland CA: AK Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9781849350136.

- Lockhart & Duiker 2010, p. 48.

- Gunn 2014, p. 119.

- Daniel Hemery Revolutionnaires Vietnamiens et pouvoir colonial en Indochine. François Maspero, Paris. 1975, Appendix 24.

- Frank N. Trager (ed.). Marxism in Southeast Asia; A Study of Four Countries. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1959. p. 142

- Daniel Hemery Revolutionnaires Vietnamiens et pouvoir colonial en Indochine. François Maspero, Paris. 1975, p. 388

- Manfred McDowell, "Sky without Light: a Vietnamese Tragedy," New Politics, Vol XIII, No. 3, 2011, p. 1341 https://newpol.org/review/sky-without-light-vietnamese-tragedy/ (accessed 10 October 2019).

- Van, Ngo (2010). In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary. Oakland CA: AK Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781849350136.

- Tyson, James L. (1974). "Labor Unions in South Vietnam". Asian Affairs. 2 (2): 70–82. doi:10.1080/00927678.1974.10587653. JSTOR 30171359.

- Chonchirdsim, Sud (November 1997). "The Indochinese Communist Party and the Nam Ky Uprising in Cochin China November December 1940". South East Asia Research. 5 (3): 269–293. doi:10.1177/0967828X9700500304. JSTOR 23746947.

- Paige, Jeffery M. (1970). "Inequality and Insurgency in Vietnam: A re-analysis" (PDF). cambridge.org. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- Marr, David G. (15 April 2013). Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945–1946). University of California Press. pp. 408–409. ISBN 9780520274150.

- Concert to mark 66th anniversary of the Southern Resistance War Archived 2011-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Gutzlaff, Charles (1849). "Geography of the Cochin-Chinese Empire". Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 19: 85–143.

- Li, Tana (1998). Nguyen Cochinchina: Southern Vietnam in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

![]() Media related to Cochinchina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cochinchina at Wikimedia Commons