Cold-air damming

Cold air damming, or CAD, is a meteorological phenomenon that involves a high-pressure system (anticyclone) accelerating equatorward east of a north-south oriented mountain range due to the formation of a barrier jet behind a cold front associated with the poleward portion of a split upper level trough. Initially, a high-pressure system moves poleward of a north-south mountain range. Once it sloshes over poleward and eastward of the range, the flow around the high banks up against the mountains, forming a barrier jet which funnels cool air down a stretch of land east of the mountains. The higher the mountain chain, the deeper the cold air mass becomes lodged to its east, and the greater impediment it is within the flow pattern and the more resistant it becomes to intrusions of milder air.

As the equatorward portion of the system approaches the cold air wedge, persistent low cloudiness, such as stratus, and precipitation such as drizzle develop, which can linger for long periods of time; as long as ten days. The precipitation itself can create or enhance a damming signature, if the poleward high is relatively weak. If such events accelerate through mountain passes, dangerously accelerated mountain-gap winds can result, such as the Tehuantepecer and Santa Ana winds. These events are seen commonly in the northern Hemisphere across central and eastern North America, south of the Alps in Italy, and near Taiwan and Korea in Asia. Events in the southern Hemisphere have been noted in South America east of the Andes.

Location

Cold air damming typically happens in the mid-latitudes as this region lies within the Westerlies, an area where frontal intrusions are common. When the Arctic oscillation is negative and pressures are higher over the poles, the flow is more meridional, blowing from the direction of the pole towards the equator, which brings cold air into the mid-latitudes.[1] Cold air damming is observed in the southern hemisphere to the east of the Andes, with cool incursions seen as far equatorward as the 10th parallel south.[2] In the northern hemisphere, common situations occur along the east side of ranges within the Rocky Mountains system over the western portions of the Great Plains, as well as various other mountain ranges (such as the Cascades) along the west coast of the United States.[3] The initial is caused by the poleward portion of a split upper level trough, with the damming preceding the arrival of the more equatorward portion.[4]

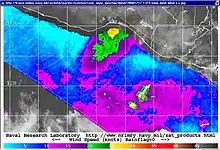

Some of the cold air damming events which occur east of the Rockies continue southward to the east of the Sierra Madre Oriental through the coastal plain of Mexico through the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Further funneling of cool air occurs within the Isthmus, which can lead to winds of gale and hurricane-force, referred to as a Tehuantepecer. Other common instances of cold air damming take place on the coastal plain of east-central North America, between the Appalachian Mountains and Atlantic Ocean.[5] In Europe, areas south of the Alps can be prone to cold air damming.[4] In Asia, cold air damming has been documented near Taiwan and the Korean Peninsula.[6][7]

The cold surges on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains, Iceland, New Zealand,[8] and eastern Asia differ from the cold air damming east of the Appalachians due to the wider mountain ranges, sloping terrain, and lack of an eastern body of warm water.[9]

Development

The usual development of CAD is when a cool high-pressure area wedges in east of a north-south oriented mountain chain. As a system approaches from the west, a persistent cloud deck with associated precipitation forms and lingers across the region for prolonged periods of time. Temperature differences between the warmer coast and inland sections east of the terrain can exceed 36 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius), with rain near the coast and frozen precipitation, such as snow, sleet, and freezing rain, falling inland during colder times of the year. In the Northern Hemisphere, two-thirds of such events occur between October and April, with summer events preceded by the passage of a backdoor cold front.[10] In the Southern Hemisphere, they have been documented to occur between June and November.[2] Cold air damming events which occur when the parent surface high-pressure system is relatively weak, with a central pressure below 1,028.0 millibars (30.36 inHg), or remaining a progressive feature (move consistently eastward), can be significantly enhanced by cloudiness and precipitation itself. Clouds and precipitation act to increase sea level pressure in the area by 1.5 to 2.0 mb ( 0.04 to 0.06 inHg).[11] When the surface high moves offshore, the precipitation itself can cause the CAD event.[12]

Detection

Detection algorithm

This algorithm is used to identify the specific type of CAD events based on the surface pressure ridge, its associated cold dome, and ageostrophic northeasterly flow which flows at a significant angle to the isobaric pattern. These values are calculated using hourly data from surface weather observations. The Laplacian of sea level pressure or potential temperature in the mountain-normal—perpendicular to the mountain chain—direction provides a quantitative measure of the intensity of a pressure ridge or associated cold dome. The detection algorithm is based upon Laplacians () evaluated for three mountain-normal lines constructed from surface observations in and around the area affected by the cold air damming—the damming region. The "x" denotes either sea level pressure or potential temperature (θ) and the subscripts 1–3 denote stations running from west to east along the line, while the "d" represents the distance between two stations. Negative Laplacian values are typically associated with pressure maxima at the center station, while positive Laplacian values usually correspond to colder temperatures in the center of the section.[13]

Effects

When cold air damming occurs, it allows for cold air to surge toward the equator in the affected area. In calm, non-stormy situations, the cold air will advance unhindered until the high-pressure area can no longer exert any influence because of a lack of size or its leaving the area. The effects of cold air damming become more prominent (and also more complicated) when a storm system interacts with the spreading cold air.

The effects of cold air damming east of the Cascades in Washington are strengthened by the bowl or basin-like topography of Eastern Washington. Cold Arctic air flowing south from British Columbia through the Okanogan River valley fills the basin, blocked to the south by the Blue Mountains. Cold air damming causes the cold air to bank up along the eastern Cascade slopes, especially into the lower passes, such as Snoqualmie Pass and Stevens Pass. Milder, Pacific-influenced air moving east over the Cascades is often forced aloft by the cold air in the passes, held in place by cold air damming east of the Cascades. As a result, the passes often receive more snow than higher areas in the Cascades, which supports skiing at Snoqualmie and Stevens passes.[14]

The situation during Tehuantepecers and Santa Ana wind events are more complicated, as they occur when air rushing southward due to cold air damming east of the Sierra Madre Oriental and Sierra Nevada respectively, is accelerated when it moves through gaps in the terrain. The Santa Ana is further complicated by downsloped air, or foehn winds, drying out and warming up in the lee of the Sierra Nevada and coastal ranges, leading to a dangerous wildfire situation.

The wedge

The effect known as "the wedge" is the most widely known example of cold air damming. In this scenario, the more equatorward storm system will bring warmer air with it above the surface (at around 1,500 metres (4,900 ft)). This warmer air will ride over the cooler air at the surface, which is being held in place by the poleward high-pressure system. This temperature profile, known as a temperature inversion, will lead to the development of drizzle, rain, freezing rain, sleet, or snow. When it is above freezing at the surface, drizzle or rain could result. Sleet, or Ice pellets, form when a layer of above-freezing air exists with sub-freezing air both above and below it. This causes the partial or complete melting of any snowflakes falling through the warm layer. As they fall back into the sub-freezing layer closer to the surface, they re-freeze into ice pellets. However, if the sub-freezing layer beneath the warm layer is too small, the precipitation will not have time to re-freeze, and freezing rain will be the result at the surface.[15] A thicker or stronger cold layer, where the warm layer aloft does not significantly warm above the melting point, will lead to snow.

Blocking

Blocking occurs when a well-established poleward high-pressure system lies near or within the path of the advancing storm system. The thicker the cold air mass is, the more effectively it can block an invading milder air mass. The depth of the cold air mass is normally shallower than the mountain barrier which created the CAD. Some events across the Intermountain West can last for ten days. Pollutants and smoke can remain suspended within the stable air mass of a cold air dam.[16]

Erosion

It is often more difficult to forecast the erosion of a CAD event than its development. Numerical models tend to underestimate the event's duration. The bulk Richardson number, Ri, calculates vertical wind shear to help forecast erosion. The numerator corresponds to the strength of the inversion layer separating the CAD cold dome and the immediate atmosphere above. The denominator expresses the square of the vertical wind shear across the inversion layer. Small values of the Richardson number result in turbulent mixing that can weaken the inversion layer and aid the deterioration of the cold dome, leading to the end of the CAD event.[9]

Cold advection aloft

One of the most effective erosion mechanisms is the import of colder air—also known as cold air advection—aloft. With cold advection maximized above the inversion layer, cooling aloft can weaken in the inversion layer, which allows for mixing and the demise of CAD. The Richardson number is reduced by the weakening inversion layer. Cold advection favors subsidence and drying, which supports solar heating beneath the inversion.[9]

Solar heating

Solar heating has the ability to erode a CAD event by heating the surface in the absence of a thick overcast. However, even a shallow stratus layer during the cold season can render solar heating ineffective. During breaks of overcast for the warm season, absorption of solar radiation at the surface warms the cold dome, once again lowering the Richardson number and promoting mixing.[9]

Near-surface divergence

In the United States, as a high-pressure system moves eastward out to the Atlantic, northerly winds are reduced along the southeast coast. If northeasterly winds persist in the southern damming region, net divergence is implied. Near-surface divergence reduces the depth of the cold dome as well as aid the sinking of air, which can reduce cloud cover. The reduction of cloud cover permits solar heating to effectively warm the cold dome from the surface up.[9]

Shear-induced mixing

The strong static stability of a CAD inversion layer usually inhibits turbulent mixing, even in the presence of vertical wind shear. However, if the shear strengthens in addition to a weakening of the inversion, the cold dome becomes vulnerable to shear-induced mixing. Unlike solar heating, this CAD event erosion happens from the top down. Mixing occurs when the depth of the northeasterly flow becomes increasingly shallow and strong southerly flow makes a downward progression resulting in high shear.[9]

Frontal advance

Erosion of a cold dome will typically first occur near the fringes where the layer is relatively shallow. As mixing progresses and the cold dome erodes, the boundary of the cold air – often indicated as a coastal or warm front – will move inland, diminishing the width of the cold dome.[9]

Classifying Southeastern United States events

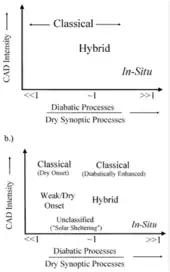

An objective scheme has been developed to classify certain types of CAD events in the Southeastern United States. Each scheme is based on the strength and location of the parent high-pressure system.

Classical

Classical CAD events are characterized by dry synoptic forcing, partial diabatic contribution, and a strong parent anticyclone (high-pressure system) located to the north of the Appalachian damming region. A strong high-pressure system usually is defined as having a central pressure over 1,030.0 mb (30.42 inHg). The northeastern United States is the most favorable location for the high-pressure system in classical CAD events. [9]

For diabatically enhanced classical events, at 24 hours prior to the onset of CAD, a prominent 250-mb jet extends from southwest to northeast across eastern North America. A general area of troughing is present at the 500- and 250-mb levels west of the jet. The parent high-pressure system is centered over the upper Midwest beneath the 250-mb jet entrance region, setting up conditions for CAD east of the Rocky Mountains.[13]

For dry onset classical events, the 250-mb jet is weaker and centered farther east relative to the diabatically enhanced classical events. The jet also does not extend as far southwest compared to diabatically enhanced classical CAD events. The center of the high-pressure system is farther east, so ridging extends southward into the south-central eastern United States. Although both types of classical events begin differently, their results are very similar.[13]

Hybrid

When the parent anticyclone is weaker or not ideally located, the diabatic process must start to contribute in order to develop CAD. In scenarios where there is an equal contribution from dry synoptic forcing and diabatic processes, it is considered a hybrid damming event.[9] The 250-mb jet is weaker and slightly farther south relative to a classical composite 24 hours prior to CAD onset. With the surface parent high farther west, it builds in eastward into the northern Great Plains and western Great Lakes region, located beneath a region of confluent flow from the 250-mb jet.[13]

In-situ

In-situ events are the weakest and often most short lived out of CAD event types. These events occur during the absence of ideal synoptic conditions, when the anticyclone position is highly unfavorable located well offshore.[9] In some in situ cases, the barrier pressure gradient is largely due to a cyclone to the southwest rather than the anticyclone to the northeast.[13] Diabatic processes lead to the stabilization of an air mass approaching the Appalachians. Diabatic processes are essential for in-situ events. These events often lead to weak, narrow damming.[9]

Prediction

Overview

Weather forecasts during CAD events are especially prone to inaccuracies. Precipitation type and daily high temperatures are especially difficult to predict. Numerical weather models tend to be more accurate in predicting the development of a CAD event, and less accurate in predicting their erosion. Manual forecasting can provide more accurate forecasts. An experienced human forecaster will use numerical models as a guide, but account for the model's inaccuracies and shortcomings. [17]

Example case

The Appalachian CAD event of October 2002 illustrates some shortcomings of short-term weather models for predicting a CAD event. This event was characterized by a stable saturated layer of cold air from surface up to the 700mb pressure level over the states of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. This mass of cold air was blocked by the Appalachians and did not dissipate even as a coastal cyclone to east strengthened. During this event, short term weather models predicted this cold mass clearing, leading to fairer weather conditions for the region such as warmer conditions and the absence of a layer of stratus clouds. However, the model performed poorly because they did not account for excessive solar radiation transmission through the cloud layers and shallow mixing promoted by the model's convective parameterization scheme. While these errors have been corrected in updated models, they resulted in an inaccurate forecast.[9]

References

- National Snow and Ice Data Center (2009). The Arctic Oscillation. Arctic Climatology and Meteorology. Retrieved on 2009-04-11.

- René D. Garreaud (July 2000). "Cold Air Incursions over Subtropical South America: Mean Structure and Dynamics" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 128 (7): 2547–2548. Bibcode:2000MWRv..128.2544G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2000)128<2544:caioss>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Ron Miller (2000-12-14). "Cold Air Damming Along the Cascade East Slopes". Retrieved 2007-02-17.

- W. James Steenburgh (Fall 2008). "Cold-Air Damming" (PDF). Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- Geoffery J. DiMego; Lance F. Bosart; G. William Endersen (June 1976). "An Examination of the Frequency and Mean Conditions Surrounding Frontal Incursions into the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea". Monthly Weather Review. 104 (6): 710. Bibcode:1976MWRv..104..709D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1976)104<0709:AEOTFA>2.0.CO;2.

- Fang-Ching Chien; Ying-Hwa Kuo (November 2006). "Topographic Effects on a Wintertime Cold Front in Taiwan". Monthly Weather Review. 134 (11): 3297–3298. Bibcode:2006MWRv..134.3297C. doi:10.1175/MWR3255.1.

- Jae-Gyoo Lee; Ming Xue (2013). "A Study on a Snowband Associated With a Coastal Front and Cold-Air Damming Event of 3–4 February 1998 Along the Eastern Coast of the Korean Peninsula". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 30 (2): 263–279. Bibcode:2013AdAtS..30..263L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.303.9965. doi:10.1007/s00376-012-2088-6.

- Ronald B. Smith (1982). "Synoptic Observations and Theory of Orographically Disturbed Wind and Pressure". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 39 (1): 60–70. Bibcode:1982JAtS...39...60S. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1982)039<0060:soatoo>2.0.co;2.

- Gary Lackmann (2012). <Midlatitude Synoptic Meteorology: Dynamics, Analysis, & Forecasting>. 45 Beacon Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02108: American Meteorological Society. pp. 193–215. 978-1878220103.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Gerald D. Bell; Lance F. Bosart (January 1988). "Appalachian Cold Air Damming". Monthly Weather Review. 116 (1): 137–161. Bibcode:1988MWRv..116..137B. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1988)116<0137:ACAD>2.0.CO;2.

- J. M. Fritsch; J. Kapolka; P. A. Hirschberg (January 1992). "The Effects of Subcloud-Layer Diabatic Processes on Cold Air Damming". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 49 (1): 49–51. Bibcode:1992JAtS...49...49F. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1992)049<0049:TEOSLD>2.0.CO;2.

- Gail I. Hartfield (December 1998). "Cold Air Damming: An Introduction" (PDF). National Weather Service Eastern Region Headquarters. Retrieved 2013-05-16.

- Christopher M. Bailey; Gail Hartfield; Gary Lackmann; Kermit Keeter; Scott Sharp (Aug 2003). "An Objective Climatology, Classification Scheme, and Assessment of Sensible Weather Impacts for Appalachian Cold-Air Damming". Weather and Forecasting. 18 (4): 641–661. Bibcode:2003WtFor..18..641B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2003)018<0641:aoccsa>2.0.co;2.

- Cliff Mass (2008). The Weather of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington Press. pp. 66–70. ISBN 978-0-295-98847-4.

- Weatherquestions.com (2012-07-06). "What causes ice pellets (sleet)?". Weatherstreet.com. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- C. David Whiteman (2000). Mountain Meteorology : Fundamentals and Applications. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780198030447.

- Clayton Stiver. "Cold Air Damming: Setup, Forecast Methods/Challenges for the Eastern US". Retrieved 3 October 2013.