Congo–Arab War

The Congo–Arab War (also known as the Congolese–Arab War, Belgo–Arab War or Arab Wars) took place in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo between the forces of Belgian King Leopold II's Congo Free State and various Zanzibari Arab slave traders led by Sefu bin Hamid, the son of Tippu Tip. Fighting occurred in the eastern Congo between 1892 and 1894. It was a proxy war, with most of the fighting being done by native Congolese, who aligned themselves with either side and sometimes switched sides.[2] The causes of the war were largely economic based, since Leopold and the Arabs were contending to gain control of the wealth of the Congo.[3] The war ended in January 1894 with a victory of Leopold's Force Publique. Initially, King Leopold II collaborated with the Arabs, but competition struck over the control of ivory and the topic of Leopold II's humanitarian pledges to the Berlin Conference to end slavery. Leopold II's stance turned confrontational against his once-allies.[4] The war against the Swahili-Arab economic and political power was presented as a Christian anti-slavery crusade.[4]

| Congo–Arab War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the end of the East African slave trade | |||||||

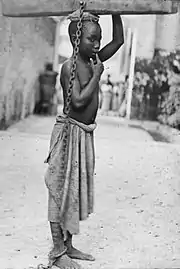

Three men of Dugumbé ben Habib raiding the market of Nyangwe, July 15th, 1871 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

3,500 regular soldiers Around 10,000 total. | ~10,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Several tens of thousands killed[1] | |||||||

Prelude

In 1886, while Tippu Tip was in Zanzibar, a dispute arose between a fort at Stanley Falls led by Tippu Tip, and a smaller, nearby Congo Free State fort led by Walter Deane (a British captain) and Lt Dubois (a Belgian lieutenant). Tip's men at the Stanley Falls fort alleged that Deane had stolen a slave woman from an Arab officer there. Deane asserted that the girl had fled after being badly beaten by her master, and that he had only offered her refuge.[5]

Tippu Tip's men attacked the fort — the Congo Free State fort was defended by the two officers, eighty Nigerian Hausas and sixty local militiamen — and after a four-day siege, the defenders ran out of ammunition and fled, abandoning the fort.[6] The Free State made no counterattack, and Tippu Tip began to move more men into the Congo, including several Arab slaver captains and also some Congolese leaders, such as Gongo Lutete.[6]

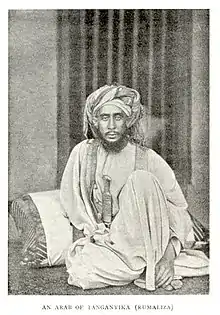

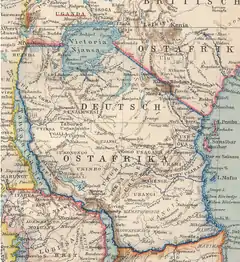

Initially, the authority of the Congo Free State was relatively weak in the eastern regions of the Congo. In early 1887, Henry Morton Stanley arrived in Zanzibar and proposed that Tippu Tip (nom de guerre—his real name was Hamad bin Muhammad bin Juma bin Rajab el Murjebi) be made governor (wali) of the Stanley Falls District in the Congo Free State. Both Leopold II and Barghash bin Said agreed and on February 24, 1887, Tippu Tip accepted.[7] Tippu Tip agreed to submit to Congo Free State authority and to allow a Congo Free State Resident by his side to help him govern this territory—inspired by the indirect rule governance system used by the British Empire and in the Dutch East Indies. The borders of his territories were the Aruwimi and the Lualaba River. Additionally Tippu Tip was to redirect his ivory trade through the Congo Free State, to the ports located at the Atlantic Ocean and he was to assist King Leopold II ‘s forces in their expeditions to the Upper Nile, to help further expand his territories. Soon after making this deal, it became apparent that Tippu Tip was not inclined to accept Congo Free State authority and considered himself more of a vassal than a state official, allowed to do as he pleased, within certain boundaries. Furthermore, Tippu Tip did not have absolute authority over the eastern Congo region, but was considered as a primus inter pares. Other major slave traders like Rumaliza, the strongman of Lake Tanganyika, considered his deal with the Congo Free State to be treason. Rumaliza abolished the Congo Free State flag and swore loyalty to the red flag of the sultan of Zanzibar.

Leopold II was heavily criticized in European public opinion for his dealings with Tippu Tip. In Belgium, the Belgian Anti-Slavery Society, founded in 1888, mainly by Roman Catholic intellectuals led by count Hippolyte d'Ursel, aimed to abolish the East African slave trade .

Around 1890-91, Tippu Tip returned to Zanzibar, where he retired; Sefu bin Hamid represented his father in the eastern Congo region of Kasongo and carried on the war in his stead.

Course of the war

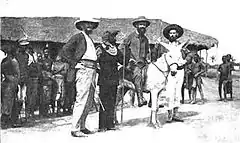

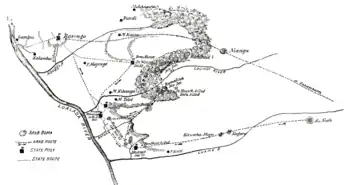

In March and April 1892, Tippu Tip's son Sefu bin Hamid began to lead various attacks on Congo Free State (CFS) personnel in the eastern Congo, including ivory trader Arthur Hodister—sent by the Syndicat Commercial du Katanga to 'acquire' ivory—and Captain Guillaume Van Kerckhoven, who had been confiscating ivory by force from several powerful Arab traders.[8] These expeditions played a huge role in uniting the slave and ivory traders in the region, in the fight against their common enemy, the Congo Free State.[9] In 1892 The Times reported that, during further explorations in the Congo, Hodister was captured and killed, his head stuck on a pole. Relations were further strained when Rashid ben Mohammed, Tippu Tip's nephew and resident Arab leader in Stanley Falls, refused to assist in the investigation of Hodister's death.[10] Gongo Lutete also led actions in the east at this time.[11]

Initial hostilities

The Force Publique, under Francis Dhanis, was sent to Katanga to resupply the trading post of Lofoi, and establish new outposts on his path. During this mission, the Force Publique crossed paths with the soldiers of Gongo Lutete— captured by Tippu Tip as a boy, after winning his freedom he became the leader of the Batetela and Bakusu tribes. Gongo Letete was heading to Kasaï in the west, to pick up weapon supplies from Angola, in an attempt to strengthen his position in the Lomani region.

After several skirmishes in April–May 1892 with the better equipped Free State forces of Dhanis and Michaux, Ngongo Lutete decided to make a deal with the Congo Free State. On the 19th of September he switched sides and joined the Force Publique - other native leaders like Pania Mutomba before him and Lupungu, chief of the Songe at Kabinda shortly thereafter, also had joined the Force Publique.

Maniema campaign

By October 1892, Sefu was leading a force of 10,000 men, some 500 Zanzibari officers and the remaining were Congolese.[8] The Force Publique army under the command of Francis Dhanis, consisted of a few dozen Belgian officers and several thousand African auxiliaries.[12] Open warfare broke out in late November 1892, when Sefu set up a fort on the Lomami River, where he was attacked by the Force Publique and eventually was forced to retreat.[12] Dhanis used this battle as a pretext for advancing against the Arabs in force.[13] He allowed his army to travel with all of their wives, slaves, and servants, who did all of the army's cooking and cleaning and acted as a supply train.[14] In addition, he did not allow his men to harm local non-combatants, earning him goodwill of the local Congolese people.[14]

Rumaliza campaign

By this time, the Congo Free State gained in military strength in the region and became less tolerant of "Arab" strongmen, determined to stamp them out.[15] The Congo Free State forces under Francis Dhanis launched a new campaign against the slave traders in 1892, and Rumaliza was one of the main targets.[16]

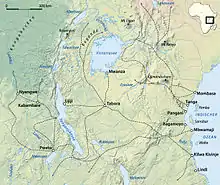

By 1892, the Swahili slave and ivory trader Rumaliza dominated Tanganyika from his base at Ujiji on the old slave route that led from Stanley Falls up the Lualaba River to Nyangwe, east to Lake Tanganyika and then via Tabora to Bagamoyo opposite Zanzibar. The total number of Swahili fighters in this huge region numbered around one hundred thousand, but each chief acted independently from the main body. Although experienced in warfare, they were poorly armed with simple rifles. The Belgians had just six hundred troops divided between the camps at Basoko and Lusambo, but were much better armed and had six cannons and a machine gun.[17]

In the previous years (1886-1891), the Society of Missionaries of Africa had founded Catholic missions at the north and south ends of Lake Tanganyika. Léopold Louis Joubert, a French soldier and armed auxiliary, was dispatched by Archbishop Charles Lavigerie's Society of Missionaries of Africa to protect the missionaries. The missionaries abandoned three of the new stations due to attacks by Tippu Tip and Rumaliza.[18] By 1891, the slavers had control of the entire western shore of the lake, apart from the region defended by Joubert around Mpala and St Louis de Mrumbi.[19] The anti-slavery expedition under Captain Alphonse Jacques—financed by the Belgian Anti-Slavery Society—came to the relief of Joubert on 30 October 1891.[20] When the Jacques expedition arrived Joubert's garrison was down to about two hundred men, poorly armed with "a most miscellaneous assortment of chassepots, Remingtons and muzzle-loaders, without suitable cartridges." He also had hardly any medicine left.[21][22][23] Captain Jacques asked Joubert to remain on the defensive while his expedition moved north.[24]

On the 3rd of January 1892, Captain Alphonse Jacques' anti-slavery expedition founded the fortress of Albertville on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, and tried to put an end to the slave trade in the region. Rumaliza's troops surrounded Albertville on the 5th of April and besieged the outpost for 9 months. Eventually Rumaliza's forces had to retreat because of the arrival of the Long-Duvivier-Demol Anti-Slavery expedition, a relief column sent from Brussels at captain Alphonse Jacques's aide.[20]

The capture of Nyangwe and Kasongo

On 4 March 1893 the Congo Free State forces under Francis Dhanis took control of a key river city by the name of Nyangwe after a 6-week standoff that devastated the city. Of the 1000 original buildings in the city, only one remained standing.[25][26][27][28]

On the 9th of March, the Congo Free State encampment at Nyangwe was struck by a virulent form of influenza; by the end of the first week, nearly all men were infected. At about that time, Sefu began sending smallpox cases from all over the district to Nyangwe, his ruse succeeded, and influenza was followed by an epidemic of smallpox. The mortality both from smallpox and influenza among Lutete's people and the other native allies of the Congo Free State was substantial.[29] Following these events, Sefu sent ambassadors to Nyangwe, bringing with them Lutete's oldest son and daughter, whom he had held as hostages, in return for a 10-day ceasefire. Dhanis agreed, giving his soldiers a chance of recovering from the effects of their sickness.

Commandant Gillian arrived with Congo Free State reinforcements on the 13th of April. Dhanis advanced up the river to Kasongo on 22 April 1893, while sending Lieutenant Doorme and his advanced-guard to encircle the city, surprising the Arab slavers and taking all their defenses in the rear. The force publique found a huge supply store at Kasongo including ivory, ammunition, food and luxuries such as gold and crystal tableware. For the next six months, Dhanis remained inactive, setting up supply routes and befriending the local tribes, while Rumaliza's forces were swelled by Swahili fighters who had escaped after earlier defeat by Dhanis.[30]

Fight for the Stanley Falls

In 1893, Louis-Napoléon Chaltin was head of the Force Publique station at Basoko—the camp at Basoko had been established by the Congo Free State as a precaution, in the event of a quarrel with the Arab slave and ivory traders at Stanley Falls.[31] Captain Chaltin and Richard Mohun—a commercial agent for the United States and the commander of the artillery battery attached to this expedition—were ordered in May 1893 to join Captain Dhanis' forces near Kasongo. Chaltin went up the Lomami River to Bena-Kamba with two river steamers, then striking overland to Riba Riba, near present-day Kindu.[32] At this point, smallpox had broken out in his caravan and Chaltin was forced to return to Basoko. Chaltin arrived at Stanley Falls on the 18th of May, where Captain Tobback and Lieutenant Van Lint had for five days been resisting the attacks of the forces of Rashid ben Mohammed, the nephew of Tippu Tip.[32] On the landing of the troops from Basoko at Stanley Falls, the Arab attackers decamped, leaving the town. After defeating them again at Kirundu, the Arab traders were expelled from the region.[33] Chaltin went on to secure the Dungu region in the northeast of the Congo Free State, and was commander of the Haut-Uélé district from 1893.

On the 25th of June 1893, Commandant Pierre Ponthier arrived at the Stanley Falls from Europe. He immediately collected all the troops he could, took Captain Hubert Lothaire and some men from Bangala with him and followed the Arab units, who had fled from the Stanley Falls up the river. After some severe fighting and many skirmishes, he cleared the river and its neighbourhood, as far as Nyangwe. During a fortnight's severe fighting, Commandant Ponthier's attacks on the forts of Rumaliza failed and Ponthier was killed in action.[34]

Rumaliza's last stand

In 1893 Tippu Tip advised Rumaliza to retire from the trade, but Rumaliza first had to look after his people at Lake Tanganyika.[15] Rumaliza raised a strong force, which clashed with Dhanis' column on 15 October 1893 causing the death of two European leaders and fifty of their soldiers. On 19 October 1893 Rumaliza attacked a position one day's march from Kasongo.[35] Dhanis concentrated his forces and defeated Rumaliza.

The war's last major battle occurred on 20 October 1893, on the Luama River, west of Lake Tanganyika.[36] It was a tactical stalemate, but Sefu was killed,[37] and the remaining resistance soon fell apart.[38][39] By 24 December 1893, Dhanis had obtained reinforcements and was ready to advance again. Rumaliza had also received assistance. Dhanis sent one column under Gillain to prevent Rumaliza from retreating, and another under De Wouters to advance on Rumaliza's fort near Bena Kalunga. A group of fresh forces coming to Rumaliza's aid from German East Africa was headed off, and Dhanis's forces closed in on Rumaliza's bomas (Swahili for fort).[40] On 9 January 1894 Belgian reinforcements arrived under Captain Hubert Lothaire, and the same day a shell blew up Rumaliza's ammunition store and burned down the fort containing it. Most of the occupants were killed while attempting to escape. Within three days the remaining forts, cut off from water and other supplies, surrendered. More than two thousand prisoners were taken. [41] A column under Lothaire pursued him to the north of Lake Tanganyika, destroying his fortified positions along the route, although Rumaliza himself managed to escape. At the lake they joined with the anti-slavery expedition led by Captain Alphonse Jacques[20] Rumaliza took refuge in the German colony of German East Africa.[30] The war ended in a victory for the Free State by January 1894.

Aftermath and impact

The war resulted in tens of thousands of deaths among both combatants and civilians,[1] and significantly altered the political and economic geography of the Congo. The market around Nyangwe ceased to exist, while the city of Kasongo was all but destroyed.[42] With the absence of these markets and the Arab traders themselves, much of the exports of the Congo were rerouted from their destinations in East Africa to the Stanley Pool and the Atlantic Ocean.[43] The participation of the Batetela and Bakusu tribes in the war marked the transcendence of their societies' traditional values by desires for wealth and power through expansionism, assimilation, and cultural exchange. Their involvement in the slave trade made Belgian authorities wary of them, and in turn they were neglected during colonial rule.[44]

References

- Notes

- Osterhammel (2015), p. 441.

- Edgerton, pp. 94–95

- Edgerton, p. 85

- Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja: The Congo: From Leopold to Kabila: A People's History, 2002, ISBN 1842770535, page 21.

- Edgerton, Robert.(2002) The Troubled Heart of Africa: A History of the Congo. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30486-2

- Edgerton, p. 94

- Bennett and Brode

- Edgerton, p. 99

- Edgerton, p. 98

- Boulger, p. 162

- Ewans, Martin (2001). European atrocity, African catastrophe: Leopold II, the Congo Free State and its aftermath. Richmond: Curzon. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-7007-1589-3.

- Cyclopedia, p. 190

- Pakenham, p. 433

- Edgerton, p. 100

- Oliver 1985, p. 569.

- Ergo 2005, p. 41.

- Ndaywel è Nziem, Obenga & Salmon 1998, p. 296.

- "Il y a 80 ans, le 27 Mai 1927, Mourait le Captiaine Joubert" (in French). Lavigerie. Retrieved 2013-04-09.

- Shorter, Aylward (2003). "Joubert, Leopold Louis". Dictionary of African Christian Biography. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- Ergo 2005, p. 43.

- Moloney, Joseph Augustus (30 July 2007). With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–1892. Jeppestown Press.p.56. ISBN 978-0-9553936-5-5.

- Swann, Alfred J. (6 December 2012). Fighting the Slave Hunters in Central Africa: A Record of Twenty-Six Years of Travel and Adventure Round the Great Lakes. Routledge.p.34. ISBN 978-1-136-25681-3.

- Cheza, Maurice (2005). "L'accompagnement arme- des missionaires dans l'Afrique des Grand Lacs: Les cas de Joubert et Vrithoff". Les conditions matérielles de la mission: contraintes, dépassements et imaginaires, XVIIe-XXe siècles : Actes du colloque conjoint du CREDIC, de l'AFOM et du Centre Vincent Lebbe : Belley (Ain) du 31 août au 3 septembre 2004 (in French). KARTHALA Editions. p. 96. ISBN 978-2-84586-682-9.

- Swann, p. 34.

- Hinde 1897, p. 180.

- Edgerton, pp. 102–104

- Wack, p. 192

- Hinde 1897, p. 182.

- Hinde 1897, p. 176.

- Ndaywel è Nziem, Obenga & Salmon 1998, p. 297.

- Lotar & Coosemans 1948, pp. 229.

- Ndaywel è Nziem 1998, p. 301.

- Auzias & Labourdette 2006, p. 180.

- Hinde 1897, p. 215.

- Ergo 2005, p. 42.

- Vandervort, Bruce (1998). Wars of imperial conquest in Africa, 1830-1914. Indiana University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0-253-21178-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hinde 1897, p. 231.

- Edgerton 104

- Ewans, p. 140

- Boulger 1898, p. 179.

- Boulger 1898, p. 180.

- Hinde 1897, p. 6.

- Hinde 1897, p. 7.

- Willame 1972, p. 110.

- Bibliography

- American Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events, Volume 33. 1894.

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh (1898). The Congo State. London: W. Thacker & co.

- Edgerton, Robert B. (2002). The Troubled Heart of Africa: A History of the Congo. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30486-2.

- Ewans, Martin (2002). European atrocity, African catastrophe: Leopold II, the Congo Free State and its aftermath. Psychology Press. ISBN 0-7007-1589-4.

- Hinde, Sidney Langford (1897). The Fall of the Congo Arabs.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moloney, Joseph (2007). With Captain Stairs to Katanga: Slavery and Subjugation in the Congo 1891–1892. Jeppestown Press. ISBN 978-0-9553936-5-5.

- Swann, Alfred J. (2012). Fighting the Slave Hunters in Central Africa: A Record of Twenty-Six Years of Travel and Adventure Round the Great Lakes. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-25681-3.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The scramble for Africa: white man's conquest of the dark continent from 1876 to 1912. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-380-71999-1.

- Wack, Henry Wellington (1905). The story of the Congo Free State: social, political, and economic aspects of the Belgian system of government in Central Africa. G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 177–195.

- Willame, Jean-Claude (1972). Patrimonialism and Political Change in the Congo. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804707930.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Osterhammel, Jürgen (2015). The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century. Translated by Patrick Camiller. Princeton, New Jersey; Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691169804.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Congo Free State's campaign against the Arabo-Swahilis. |