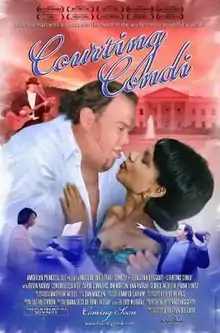

Courting Condi

Courting Condi is a 2008 film by British filmmaker Sebastian Doggart that portrays the quest of a love-struck man, actor Devin Ratray, who wants to win the heart of United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice.

| Courting Condi | |

|---|---|

Official Poster | |

| Directed by | Sebastian Doggart |

| Produced by | Sebastian Doggart |

| Written by | Sebastian Doggart |

| Starring | Devin Ratray Adrian Grenier Jim Norton Condoleezza Rice Frank Luntz Carol Connors George W. Bush Lawrence Wilkerson |

| Music by | Alexandra Gordon Kerry Shaw Carol Connors Steve Earle Devin Ratray Sebastian Doggart Jess King |

| Cinematography | Matthew Woolf |

| Edited by | Dan Madden Diana DeCilio |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Plot

Devin Ratray is a musician and besotted admirer of Condoleezza Rice, 'Condi,' who travels across America, learning more about Rice from those who knew her.[1] He speaks to her childhood friends in Birmingham, Alabama. In Denver, Colorado, he performs at Red Rocks,[2] where he meets some of her former teachers, and the one man to whom Rice has been engaged, Rick Upchurch. Upchurch tells Devin that Rice made an oath to God not to have sex before she got married, and deduces that her continued single status and her enduring Christianity confirm that she is still a virgin.[3] Ratray follows Rice's rise to Provost of Stanford University, where he discovers that, while in that position, she departed from the practice of applying affirmative action to tenure. In Los Angeles, he is given courtship advice by Adrian Grenier[1] and cult comedian Jim Norton and is presented with a power ballad to send to Condi from Oscar nominated songwriter Carol Connors. When he arrives in Washington, D.C., he is assisted by Republican strategist Frank Luntz and is counseled by Newsweek editor Eleanor Clift.

Ratray also learns from various people he meets along the way about Rice's controversial statements to the 9/11 Commission. Through interactions with and clips featuring Colin Powell's Chief of Staff Lawrence Wilkerson, 9/11 Commission investigator Richard Ben-Veniste, and Congressman David Price, Ratray gets a fuller picture of how Rice's political positions and political philosophy developed and changed over the years.[4] Finally, Glenn Kessler, a Washington Post reporter and author of a book about Rice and the Bush Administration, discusses Rice's involvement with the government's use of torture during the War on Terror.[5][6]

Style

The film's creators describe it as a 'musical docu-tragi-comedy'.[4][7][8][9] It uses an actor, Ratray, to interview friends, relatives and colleagues of Dr. Rice. It combines interviews, archive footage, animated stills, dramatizations and original songs. Critics described this hybrid genre as "a heady melange of styles and aims"[7] and "a strange mash-up by many measures."[10]

History

A promo of the film screened at the IFC Center in New York City in April 2007,[11] and led to Discovery Communications commissioning the film for $600,000. In August, one week before principal photography was due to begin, Discovery suddenly announced that they had 'canceled' the film.[12] This followed pressure from Karl Rove,[1] who had found out about the film's critical stance on the Bush Administration and warned Discovery that the movie could damage their "good relations with government".[4][8][13] Discovery settled with the producers, American Princess LLC, for a $150,000 'kill loan', forcing the producers to make the film on a shoestring.[14]

The Bush Administration continued to obstruct the film, sending State Department officials to raid the producers' guesthouse in Washington DC, and plant a bug under a coffee table in their living room—actions which were documented on camera and broadcast on the internet.[15] In February 2008, Channel 4 in the UK provided further financing for the film,[16] leading to its completion in September 2008.

Tensions between Rice and the film's producers continued in the film's marketing and distribution stage. On October 28, 2008, the Stanford Film Society invited the film to screen at Stanford University where Rice was due to return as a fellow. The SFS President Kerry Mahuron wrote: "I have seen the movie and am interested in showing it. However, as you are probably aware, Condoleezza Rice is a current faculty member of the Political Science Department at Stanford, and starting next February will be returning to the University as our Vice Provost. Showing a film that paints her in such a negative light is not only controversial, but also potentially inflammatory and a violation of Stanford policies." Despite these concerns, Mahuron proceeded to confirm a December 2 booking, arguing that "to prevent us from showing the film would violate our right to free speech, so I don't anticipate them being able to stop us."[13]

The SFS also scheduled a post-screening debate on the motion that "This house believes that Stanford University would be well served by welcoming back Condoleezza Rice to its faculty". The SFS invited conservative supporters of Rice, including Stanford fellow, Donald Rumsfeld, to debate in support of the motion. The film's director, Sebastian Doggart, was due to oppose the motion. The 500-seater Cubberley Auditorium was tagged as the venue; flyers and posters were ready for circulation, and invitations sent to the Hoover Institute, Stanford Daily, Intermissions, Stanford College Republicans, Stanford Review, Stanford Conservative Society, Stanford Amnesty, and Stanford Iraq Coalition.

On November 21, Mahuron sent an email to all these groups, stating that the Society had "resolutely decided to cancel the screening." She wrote to the film's director, Sebastian Doggart, stating that the film had been canceled for "logistical reasons... Stanford's two conservative political groups are also hosting an event on the night of December 2, and we were counting on their members to attend the screening and lend plurality to the audience and the Q&A session. December 5 is not an option, because the Stanford's MFA Program in Documentary Filmmaking is hosting its own event that evening, and, since SFS and the MFA Program support each other, we do not want to schedule competing events."[17] Mahuron gave a second reason for the cancellation: "we are now convinced that any debate following the film would not be balanced, and that this event would not be a forum for open and bipartisan political discussion."

Doggart wrote to Mahuron, suggesting they re-schedule the screening until January, to give them time to set up a "balanced" debate. When Mahuron did not reply, American Princess released a press release stating that “the gutless cancellation of this debate is self-censorship at best and direct censorship by Dr. Rice’s friends, at worst. She is clearly trying to gloss over her tragic legacy with all the resources at her disposal."

Mahuron then told the San Jose Mercury News stating that the reason she had canceled the film because "put simply, it was bad". American Princess issued a counter-statement, questioning why Mahuron had suddenly changed her mind about the quality of the film when she was the person who had invited the film to screen. It stated: "Come on Stanford Film Society, step up here! We all know Condoleezza Rice is an expert on Stalin, but do you really not have the cojones to stand up to this blatant violation of free speech? Sure, she is due to be your next vice-Provost in February, but is that really so frightening a prospect that you have to concoct untruthful stories for muzzling criticism of Stanford's most sacred cow? Screen the film in January, organize the debate in a balanced way, and let Stanford students decide for themselves."[18]

Meantime, various Stanford groups such as Stanford Amnesty and Stanford Says No to War wrote to the Stanford Film Society to re-instate or re-schedule the screening. Commenting on the story, Radar magazine wrote: "Wow. We thought this was a country where even Iran's radical prez could speak at Columbia University."[19]

John McMahon, editor of the [dis]claimer newspaper at the University of Denver, where Rice was an undergraduate, responded by organizing a screening of the movie on March 2, 2009, followed by a debate on the motion 'This house believes that Condoleezza Rice should stand trial for war crimes.' Proposing the motion was Rice's political theory professor, Alan Gilbert; defending Rice was Republican State Senator Sean Mitchell.[20] The event met fierce resistance from the University administration. Vice Chancellor Jim Berscheidt had already tried to shut down a shoot and denied the producers access to archive of Josef Korbel. Up until the last moment, Berscheidt sought to use bureaucratic obstacles and straight intimidation of students to stop the event. However, the screening and debate did eventually take place, with a strong turn-out,[21] and webcast on both Mogulus television[22] and through the Amnesty International website.[23]

Courting Condi screened at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival[24] and began its US theatrical run on May 29, 2009 at the Gene Siskel Center in Chicago.[25] It was scheduled for general international release with IndiesDirect on December 2, 2009.[26][27]

Awards

The film had advance screenings at festivals across the globe, and won many awards, including wins in both Best Documentary and Best Narrative Feature categories. At the Milan International Film Festival, the film won the Leonardo's Horse Award for Best Documentary.[28] At the DaVinci Film Festival, the film won the Audience Award for Best Feature Film. At the New Beijing International Film Festival, it won the Golden Duck for Best Long Narrative.[29] At the Garden State Film Festival, it won the Bud Abbott Award for Best Feature Length Comedy,[30] and at White Sands International Film Festival, it won Best Narrative Feature.[31] At the International Film Festival of South Africa, it won Best Documentary.[32] Orlando Film Festival selected the film as the Opening Night film,[33] and awarded it three prizes: Best Performance (Devin Ratray), and second prize for Best Picture and Best Director categories.[34] At Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival, the film won Special Award: Most Creative Concept. At Paso Robles International Film Festival, the film won Best Comedic Documentary,[35] and at Connecticut Film Festival, it won Best Political Satire. At the Mammoth Film Festival, where the film was selected as Opening Night performance, the film won Best Comedy/Musical.[36] At the Cinema City Film Festival in Novi Sad, Serbia, it won Best Socially Responsible Film.[37] At the Treasure Coast International Festival, the film was selected for the Opening Night screening, and won awards in four categories: Audience Choice Award (as voted by audiences throughout the festival), Best Documentary, Best Director (Sebastian Doggart), and Best Song (Carol Connors' Condoleezza Condi, I think of you so Fondly).[38] At the Tallahassee Film Festival, composer Carol Connors won the award for Outstanding Achievement for Music in Film for the three songs she wrote.[39] At the 42nd annual WorldFest Houston International Film Festival, it won the Special Jury Remi Award; it won the Bronze Palm for Excellence in Film-making at the Mexico International Film Festival, it won the Bronze Palm for Excellence in Filmmaking;[40] at the Honolulu International Film Festival, it won the Gold Kahuna Award for Documentary;[41] at the Tallahassee Film Festival it won a special award for Outstanding Achievement for Music in Film (Carol Connors); at the British Film Festival of Los Angeles, it won three awards: Best American Documentary, Best Comedy, and Best Song (Invisible);[42] and at Mockfest Hollywood, Carol Connors won Best Cameo.[43]

References

- "Move Over W - Condi Is Getting Her Own Movie". Radar Online. 2008-10-31. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Myspace". Vids.myspace.com. 2007-12-07. Archived from the original on 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Documentary Director Says Condi's a Virgin". Radar Online. 2008-11-03. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- Crawford, Jan (2008-04-09). "Sources: Top Bush Advisors Approved 'Enhanced Interrogation' - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "For the love of Condi - Broadsheet". Salon.com. 2008-10-31. Archived from the original on 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Controversial Film on Condi Rice to Screen at WPU - News - Pioneer Times - William Paterson University". Pioneertimeswpu.com. 2009-03-05. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "news | festivals & awards Award winning US doc for SA festival". www.screenafrica.com. 2009-11-04. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- Shepherd, Lindy T. (2008-11-06). "Film: Freebie Flicks". Orlandoweekly.com. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- http://www.filmcollection.org

- "Film International | Thinking Film Since 1973". Filmint.nu. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Stalking, Courting or Pimping Condi? | SMASHgods ~ breaking down the best bits of propriety ~ [www.smashgods.com]". Smashgods.com. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Documentary Director Says Condi's a Virgin". Radar Online. 2008-11-03. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Courting Condi - Raided and Bugged by Condi's Goons". YouTube. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Television Shows Resource Online Search Resource". channel four. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ""Courting Condi" Screening Canceled: Director Blames Her "Cronies"". Huffingtonpost.com. 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Stanford Cancels Condi Screening". Radar Online. 2008-11-24. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Niet compatibele browser". Facebook. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2010-02-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- - 7:30 PM EST on Mar 2nd, 2009 (2009-03-02). "Courting Condi - live streaming video powered by Livestream". Mogulus.com. Archived from the original on 2009-04-23. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Condi's former professor argues she should be tried as war criminal tonight | Human Rights Now - Amnesty International USA Blog". Blog.amnestyusa.org. 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Cinando". Cinando. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Chicago's Premier Movie Theater". siskelfilmcenter.org. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080403000854/http://www.firstmediasyndicate.com/Projects/Overview.aspx. Archived from the original on April 3, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "From Lens to Living Room". Indies Direct. Archived from the original on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "MIFF Film Festival Awards 2011 - Milano". Miff.it. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Awards". Beijingfilmfest.org. 2008-11-19. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "7th Annual Garden State Film Festival". Gsff.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2009-04-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "home". Amritsa.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Orlando Film Festival". Orlandofilmfest.com. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Contract Killers: Best Feature at Orlando Film Festival – Frankly My Dear – Orlando Sentinel". Blogs.orlandosentinel.com. 2008-11-10. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Home Filmmakers Sponsor". Pasoroblesfilmfestival.com. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "Official Website". Mammoth Film Festival. 2011-07-09. Archived from the original on 2011-08-08. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090203113505/http://tcifilmfest.com/2009/09Winners.html. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Home". Tallahassee Film Festival. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090923123908/http://www.mexicofilmfestival.com/Festival_2007/2009_Bronze_Palm_Winners.aspx. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2009. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Honolulu Film Festival. "Gold Kahuna Award Winners". Honolulufilmfestival.com. Archived from the original on 2009-04-25. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "British Film Festival Los Angeles". Britishfilmfest.com. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- "mockfilmfest.com". mockfilmfest.com. Retrieved 2011-08-07.