Cut (graph theory)

In graph theory, a cut is a partition of the vertices of a graph into two disjoint subsets. Any cut determines a cut-set, the set of edges that have one endpoint in each subset of the partition. These edges are said to cross the cut. In a connected graph, each cut-set determines a unique cut, and in some cases cuts are identified with their cut-sets rather than with their vertex partitions.

In a flow network, an s–t cut is a cut that requires the source and the sink to be in different subsets, and its cut-set only consists of edges going from the source's side to the sink's side. The capacity of an s–t cut is defined as the sum of the capacity of each edge in the cut-set.

Definition

A cut is a partition of of a graph into two subsets S and T. The cut-set of a cut is the set of edges that have one endpoint in S and the other endpoint in T. If s and t are specified vertices of the graph G, then an s–t cut is a cut in which s belongs to the set S and t belongs to the set T.

In an unweighted undirected graph, the size or weight of a cut is the number of edges crossing the cut. In a weighted graph, the value or weight is defined by the sum of the weights of the edges crossing the cut.

A bond is a cut-set that does not have any other cut-set as a proper subset.

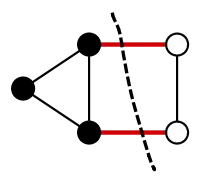

Minimum cut

A cut is minimum if the size or weight of the cut is not larger than the size of any other cut. The illustration on the right shows a minimum cut: the size of this cut is 2, and there is no cut of size 1 because the graph is bridgeless.

The max-flow min-cut theorem proves that the maximum network flow and the sum of the cut-edge weights of any minimum cut that separates the source and the sink are equal. There are polynomial-time methods to solve the min-cut problem, notably the Edmonds–Karp algorithm.[1]

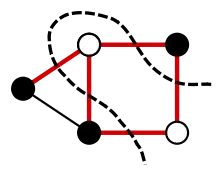

Maximum cut

A cut is maximum if the size of the cut is not smaller than the size of any other cut. The illustration on the right shows a maximum cut: the size of the cut is equal to 5, and there is no cut of size 6, or |E| (the number of edges), because the graph is not bipartite (there is an odd cycle).

In general, finding a maximum cut is computationally hard.[2] The max-cut problem is one of Karp's 21 NP-complete problems.[3] The max-cut problem is also APX-hard, meaning that there is no polynomial-time approximation scheme for it unless P = NP.[4] However, it can be approximated to within a constant approximation ratio using semidefinite programming.[5]

Note that min-cut and max-cut are not dual problems in the linear programming sense, even though one gets from one problem to other by changing min to max in the objective function. The max-flow problem is the dual of the min-cut problem.[6]

Sparsest cut

The sparsest cut problem is to bipartition the vertices so as to minimize the ratio of the number of edges across the cut divided by the number of vertices in the smaller half of the partition. This objective function favors solutions that are both sparse (few edges crossing the cut) and balanced (close to a bisection). The problem is known to be NP-hard, and the best known approximation algorithm is an approximation due to Arora, Rao & Vazirani (2009).[7]

Cut space

The family of all cut sets of an undirected graph is known as the cut space of the graph. It forms a vector space over the two-element finite field of arithmetic modulo two, with the symmetric difference of two cut sets as the vector addition operation, and is the orthogonal complement of the cycle space.[8][9] If the edges of the graph are given positive weights, the minimum weight basis of the cut space can be described by a tree on the same vertex set as the graph, called the Gomory–Hu tree.[10] Each edge of this tree is associated with a bond in the original graph, and the minimum cut between two nodes s and t is the minimum weight bond among the ones associated with the path from s to t in the tree.

See also

References

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001), Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.), MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, p. 563,655,1043, ISBN 0-262-03293-7.

- Garey, Michael R.; Johnson, David S. (1979), Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness, W.H. Freeman, A2.2: ND16, p. 210, ISBN 0-7167-1045-5.

- Karp, R. M. (1972), "Reducibility among combinatorial problems", in Miller, R. E.; Thacher, J. W. (eds.), Complexity of Computer Computation, New York: Plenum Press, pp. 85–103.

- Khot, S.; Kindler, G.; Mossel, E.; O’Donnell, R. (2004), "Optimal inapproximability results for MAX-CUT and other two-variable CSPs?" (PDF), Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 146–154.

- Goemans, M. X.; Williamson, D. P. (1995), "Improved approximation algorithms for maximum cut and satisfiability problems using semidefinite programming", Journal of the ACM, 42 (6): 1115–1145, doi:10.1145/227683.227684.

- Vazirani, Vijay V. (2004), Approximation Algorithms, Springer, pp. 97–98, ISBN 3-540-65367-8.

- Arora, Sanjeev; Rao, Satish; Vazirani, Umesh (2009), "Expander flows, geometric embeddings and graph partitioning", J. ACM, ACM, 56 (2): 1–37, doi:10.1145/1502793.1502794.

- Gross, Jonathan L.; Yellen, Jay (2005), "4.6 Graphs and Vector Spaces", Graph Theory and Its Applications (2nd ed.), CRC Press, pp. 197–207, ISBN 9781584885054.

- Diestel, Reinhard (2012), "1.9 Some linear algebra", Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 173, Springer, pp. 23–28.

- Korte, B. H.; Vygen, Jens (2008), "8.6 Gomory–Hu Trees", Combinatorial Optimization: Theory and Algorithms, Algorithms and Combinatorics, 21, Springer, pp. 180–186, ISBN 978-3-540-71844-4.