Cylinder seal

A cylinder seal is a small round cylinder, typically about one inch (2 to 3 cm) in length, engraved with written characters or figurative scenes or both, used in ancient times to roll an impression onto a two-dimensional surface, generally wet clay. According to some sources, cylinder seals were invented around 3500 BC in the Near East, at the contemporary sites of Uruk in southern Mesopotamia and slightly later at Susa in south-western Iran during the Proto-Elamite period, and they follow the development of stamp seals in the Halaf culture or slightly earlier.[4] They are linked to the invention of the latter's cuneiform writing on clay tablets.[5][6][7] Other sources, however, date the earliest cylinder seals to a much earlier time, to the Late Neolithic period (7600-6000 BC), hundreds of years before the invention of writing.[8][9] (They were used as an administrative tool, a form of signature, as well as jewelry and as magical amulets;[10] later versions would employ notations with Mesopotamian cuneiform. In later periods, they were used to notarize or attest to multiple impressions of clay documents. Graves and other sites housing precious items such as gold, silver, beads, and gemstones often included one or two cylinder seals, as honorific grave goods.

Description

The cylinder seals themselves are typically made from hardstones, and some are a form of engraved gem. They may instead use glass or ceramics, like Egyptian faience. Many varieties of material such as hematite, obsidian, steatite, amethyst, lapis lazuli and carnelian were used to make cylinder seals. As the alluvial country of Mesopotamia lacks good stone for carving, the large stones of early cylinders were imported probably from Iran.[11] Most seals have a hole running through the centre of the body, and they are thought to have typically been worn on a necklace so that they were always available when needed.

.jpg.webp)

(modern/current impressions)

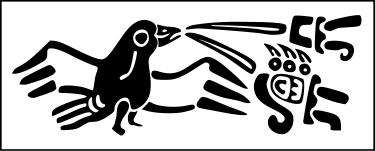

While most Mesopotamian cylinder seals form an image through the use of depressions in the cylinder surface (see lead photo above), some cylinder seals print images using raised areas on the cylinder (see San Andrés image, below, which is not related to Mesopotamian cylinder seals). The former are used primarily on wet clays; the latter, sometimes referred to as roller stamps, are used to print images on cloth and other similar two dimensional surfaces.

Cylinder seals are a form of impression seal, a category which includes the stamp seal and finger ring seal. They survive in fairly large numbers and are often important as art, especially in the Babylonian and earlier Assyrian periods. Impressions into a soft material can be taken without risk of damage to the seal, and they are often displayed in museums together with a modern impression on a small strip.

Uses

Cylinder seal impressions were made on a variety of surfaces:

- amulets

- bales of commodities

- bricks

- clay tablets

- cloth

- components of fabricated objects

- doors

- envelopes

- storage jars

Theme-driven, memorial, and commemorative nature

The images depicted on cylinder seals were mostly theme-driven, often sociological or religious. Instead of addressing the authority of the seal, a better study may be of the thematic nature of the seals, since they presented the ideas of the society in pictographic and text form. In a famous cylinder depicting Darius I of Persia: he is aiming his drawn bow at an upright enraged lion impaled by two arrows, while his chariot horse is trampling a deceased lion. The scene is framed between two slim palm trees, a block of cuneiform text, and above the scene, the Faravahar symbol of Ahura Mazda, the god representation of Zoroastrianism.

Cylinder seals

The reference below, Garbini, covers many of the following categories of cylinder seal. Dominique Collon's book First Impressions, which is dedicated to the topic, has over 1000 illustrations.

A categorization of cylinder seals:

- Akkadian cylinder seals.

- Akkadian seal, ca. 2300 BC, stone seal w/ modern impression. See National Geographic Ref. The glyptic (the Scenes) shows "God in barge", people, and offerings.

- Assyrian cylinder seals.

- Cypriote Cylinder Seals.

- Egyptian cylinder seals.

- Predynastic Egyptian Naqada era tombs and graves (imported).

- Egyptian Faience; see Pepi I ext link.

- Hittite cylinder seals.

- Clay envelope usage, etc.; see Kultepe.

- Kassite (the Kassites), cylinder seals.

- Mittanian cylinder seals.

- Old Babylonian cylinder seals.

- Persian cylinder seals; see Darius I, Robinson ref.

- Proto-Elamite cylinder seals.

- Sumerian cylinder seals.

- Seals of the "Moon-God"; see Sin.

- see Ref. (Robinson), Seal of Ur-Nammu, 2112-2095 BC. Close-up picture of Seal, and adjacent 'modern impression', high resolution, 2X-3X natural size.

- "Shamash pictographic seals"; see Mari, Syria.

- Neo-Sumerian cylinder seals.

- see Ref (Garbini), "Seated God, and Worshippers", Cylinder seal, and a modern Impressin, p. 40, (British Museum, London).

- Syrian cylinder seals.

See also

References

- British Museum notice WA 121544

- Crawford, Harriet (2013). The Sumerian World. Routledge. p. 622. ISBN 9781136219115.

- Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly (1998). Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur. UPenn Museum of Archaeology. p. 78. ISBN 9780924171550.

- Brown, Brian A.; Feldman, Marian H. (2013). Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art. Walter de Gruyter. p. 304. ISBN 9781614510352.

- Mesopotamian cylinder seals, British Museum

- Why Cylinder Seals? Engraved Cylindrical Seal Stones of the Ancient Near East, Fourth to First Millennium B.C., by Edith Porada © 1993 College Art Association., The Art Bulletin, Vol. 75, No. 4 (Dec., 1993), pp. 563-582, JSTOR

- Ancient cylinder seal found in Iran, 2 March 2009, Press TV

- https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/ancient-near-east1/sumerian/a/cylinder-seals

- https://www.ancient.eu/article/846/cylinder-seals-in-ancient-mesopotamia---their-hist/

- "Ancient Cylinder Seals". Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Why Cylinder Seals? Engraved Cylindrical Seal Stones of the Ancient Near East, Fourth to First Millennium B.C., by Edith Porada © 1993 College Art Association., The Art Bulletin, Vol. 75, No. 4 (Dec., 1993), pp. 563-582, JSTOR

- "Cylinder Seal with a Nude Goddess". The Walters Art Museum.

Further reading

- Bahn, Paul. Lost Treasures, Great Discoveries in World Archaeology, Ed. by Paul G. Bahn, (Barnes and Noble Books, New York), c 1999. Examples of, or discussions of Stamp seals, cylinder seals and a metal stamp seal.

- Collon, Dominique. First Impressions, Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East, (British Museum Press, London), 1987, 2005. Very comprehensive and up to date account, with many illustrations. The author has compiled several of the volumes cataloging the collection of cylinder seals in the British Museum.

- Collon, Dominique. Near Eastern Seals, (British Museum, London), 1990. Shorter account which also includes stamp seals . Part of the BM's Interpreting the Past series

- Frankfort, H. Cylinder Seals, 1939, London. A classic, though obviously doesn't reflect later research.

- Garbini, Giovanni. Landmarks of the World's Art, The Ancient World, by Giovanni Garbini, (McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, Toronto), General Eds, Bernard S. Myers, New York, Trewin Copplestone, London, c 1966. "Discussion, or pictures of about 25 cylinder seals"; also lists the "Scaraboid seal", an impression seal (needs to be a mirror/reverse to be an impression seal).

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cuneiform Texts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Tablets, Cones, and Bricks of the Third and Second Millennia B.C., vol. 1 (New York, 1988). The final section (Bricks) of the book concerns cylinder Seals, with a foreword describing the purpose of the section as to instigate Research into cylinder Seals. The 'cylinder sealing' on the bricks, was done multiple times per brick. Some are of high quality, and some are not. (Also contains the only 2 el Amarna letters, in the US, with Analysis.)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ancient Near Eastern Art, (Reprint), Metr. Mus. of Art Photograph Studio, Designed, Alvin Grossman, Photography, Lynton Gardiner, (Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Spring 1984)), c 1984. 56pgs.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. Beyond Babylon, Art, Trade and Diplomacy in the Second Millennium BC, ed. Joan Aruz. 2008. Many cylinder seals of the period illustrated in color with impressions and descriptions.

- National Geogr. Soc. Wonders of the Ancient World; National Geographic Atlas of Archeology, Norman Hammond, Consultant, Nat'l Geogr. Soc., (Multiple Staff authors), (Nat'l Geogr., R.H.Donnelley & Sons, Willard, OH), 1994, 1999, Reg. or Deluxe Ed. Origins of Writing, section, pp 68–75. Akkadian Cylinder seal, with its modern seal impression. p. 71.

- Robinson, Andrew. The Story of Writing, Andrew Robinson, (Thames and Hudson), c 1995, paperback ed., c 1999. (Page 70, Chapter 4: Cuneiform) Ur-Nammu cylinder seal (and impression), with 2095 BC hieroglyphs, 2X-3X; Darius I, impression only, of chariot hunting scene, 2X, ca 500 BC.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cylinder seals. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cylinder seal impressions. |

- a collection of seals and scarabs from international collectors and galleries, accompanied by an archeologist

- Seals on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets - by Mark B. Garrison and Margaret C. Root, at the Oriental Institute webpage

- Cylinder seal of Pepi I Meryre. Serpentinite, click on pictures; (possibly not meant to be an 'Impression seal').

- Kassite, Seal Impression, Department of the History of Art, University of Pennsylvania

- Seal impressions-(High Res), (1 Seal), God/Symbols explanations.

- 3D development simulation of the Cylinder Seal of Ibni Sharrum by D. Pitzalis on YouTube.