Disappearance of Larry Griffin

Laurence "Larry" Griffin (1880 – 25 December 1929[1]) was an Irish postman who disappeared from the village of Stradbally, County Waterford on Christmas Day 1929. Investigators concluded that Griffin visited a local pub after work where he was injured in a drunken altercation; he either died immediately from his injury or shortly afterwards in the adjacent Garda station.[1] His body was then allegedly disposed of in order to hide the fact that the pub was illegally serving alcohol on Christmas Day, a fact which would have threatened the livelihoods of both the publican and several members of the local police force who were supposedly drinking there.[1] This version of events has never been proven, and continues to be vehemently denied by the families of the accused.[1]

The investigation into Griffin's disappearance was hampered by conflicting witness statements and a lack of evidence. Investigators eventually arrested and charged several Stradbally residents, but the prosecution's case fell apart in court when the key witness, Jim Fitzgerald, changed his testimony.[1]:144; 258–259 All charges were subsequently dropped and the case officially remains unsolved. Fitzgerald later claimed that he had changed his testimony under duress from the villagers, and reiterated that they had been involved in Griffin's disappearance.[1]:147–149 Several Gardaí who worked on the case have also expressed their certainty of the villagers' guilt.[1]:226–238; 262–264 Despite extensive searching, Griffin's body has never been found.

Many of the accused later took successful legal action against both the Gardaí and local newspapers.[1]:186–200; 241–243; 262–264 The disappearance remains a contentious issue in Stradbally, where visitors and journalists have been verbally abused and threatened with litigation for asking about it.[1]:265–7 In 2009, all files from the original investigation were made public.[1]:298–300

Larry Griffin

Laurence "Larry" Griffin was born in Waterford, Ireland in 1880. He was a bombardier in the Artillery Regiment of the British Army from 1899 until 1907, serving in British India.[1]:22 He married Mary Fitzgerald in 1907.[1]:21

Griffin re-joined the army at the start of World War I, and was discharged on 3 June 1916 due to injuries – his arm was permanently damaged, part of his ear was missing, and he lost several of his teeth.[1]:22 For his service, he was awarded both the British War Medal and the Victory Medal in 1918.[2]

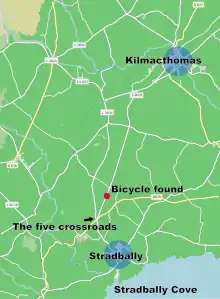

After his discharge, Griffin got a job as a postman. In 1929, he and his wife and two of his three surviving children were living in Kilmacthomas, a small town in the south east of Ireland.[1]:22His postal round covered the village of Stradbally which was about 8 miles away from Kilmacthomas.[1]:17–18

Disappearance

On 25 December 1929, Griffin attended church, delivered presents to a neighbour's children, and set off at about noon on his Post Office issue bicycle to deliver the mail in Stradbally. Local tradition called for residents to offer both money and hospitality to the postman on Christmas Day. As a result, Larry was invited to dinner in two of the households he called on and was given alcohol in many of the others. When he finished his deliveries, he called into the Post Office as normal. Griffin did not return home that night. His wife, Mary, guessed that he may have had too much to drink and decided to sleep at a friend's house, rather than risk cycling home drunk.[1]:20–27

At 7:30am the next morning, a local man walking along the road between Stradbally and Kilmacthomas discovered a postman's bicycle lying on the road, pointing toward Kilmacthomas. It appeared to have been carefully positioned there. There was no sign of Griffin.[1]:29

Search

The search commenced on 26 December. The Gardaí were quickly informed of Griffin's disappearance, and a search party consisting of Gardaí from several neighouring towns and over one hundred civilians (including postmen from Kilmacthomas) was formed. The postmen noticed that Griffin's empty mailbag, waterproof cover, overalls, and cape were strapped to the carrier of his bike in an unusual manner that postmen would generally avoid.[1]:29–31

The countryside between Kilmacthomas and Stradbally, particularly the marshlands on either side of the road where the bike had been found, were searched extensively. It was initially assumed that Griffin had wandered off the road and fallen into one of the deep holes in the adjacent bog. Despite the extensive searches, nothing was found.[1]:30–31

Investigation

Foul Play

Griffin's disappearance was reported to Chief Superintendent Harry O'Mara from Waterford on 27 December. O'Mara traveled to Stradbally and questioned the local Gardaí – Sergeant Cullinane and Gardaí Dullea, Frawley, Murphy and Sullivan. All five claimed that Griffin was sober when they had seen him.[1]:29–33 However, other villagers reported that he was "a bit jolly" and "intoxicated".[1]:27

O'Mara established that Larry had not called in to collect the mail at any locations between Stradbally and the point where his bicycle was found, even though these were part of his normal route. Another local man reported that he had been on the Stradbally to Kilmacthomas road at 4am on 26 December and had not seen the bicycle there at that time. O'Mara now suspected foul play.[1]:35–36

Conflicting statements

On 6 January 1930, Father O'Shea, a priest from a neighbouring village, told O'Mara that the Gardaí in Stradbally were concealing what had really happened, and that he should question the sixteen-year-old John Power. O'Mara interviewed Power the following day. Power had been standing outside the window of a local pub, Whelan's, with three other men for some time on the evening of 25 December, and they had seen Griffin and Garda Dullea outside the post office at 6:30pm. Dullea was pushing Griffin's bicycle, and Griffin appeared drunk and was retching. The two rounded a corner and neither returned within the next hour, at which point Power's group disbanded. Power's account was confirmed by the three men he was with.[1]:37–39

Consequently, Dullea was interviewed again. He admitted to this meeting with Griffin, and claimed he had walked with him for approximately fifty yards along the Kilmacthomas road. He reiterated that Griffin was not drunk. When asked why he had not reported this before, he said he did not think it was of any importance. Dullea claimed that after leaving Larry, he returned to the centre of the village to meet up with Cissie Whelan (daughter of the Whelan's publican), and that they walked to Stradbally Cove, not returning until 10pm. This contradicted the statements given by John Power and his friends, who claimed that Dullea did not return. Despite this, Cissie Whelan backed up Dullea's claims.[1]:39–41

At the time of Griffin's disappearance, it was illegal for pubs in Ireland to serve alcohol on either Christmas Day or Good Friday. O'Mara suspected that Dullea's conflicting statement may have been an attempt to cover up illegal drinking. Throughout January, O'Mara pieced together the events of Christmas Day, from both new witnesses and more detailed statements from existing witnesses. Shortly after 6pm, a clearly drunk Larry Griffin called into Garda Frawley's flat, accompanied by Garda Dullea. There, they had imbibed more alcohol. The three of them then went outside, where the Gardaí decided that Larry was too drunk to cycle home. Frawley went into Whelan's to see if they would put him up for the night, but realising that he had been followed in by Sergreant Cullinane (who was ensuring the premises was not serving alcohol), he left again. Garda Dullea then led Larry round the corner (passing John Power and his friends), and the two of them entered Whelan's by the back gate. None of the Gardaí had provided any of this information when they were first questioned.[1]:47–49

O'Mara turned his attention to the Stradbally Gardaí. He found that entries in the Garda barracks diary had been altered, and that many of the patrols which were recorded there had not actually been made.[1]:49–56 This, coupled with the conflicting stories convinced O'Mara that the Gardaí were involved in Griffin's disappearance. He reported this to Eoin O'Duffy, the Chief Commissioner of the Garda Síochána. He also reported that Gardaí Dullea and Murphy were "influencing the people to make false statements and are visiting those from whom statements have been made to ascertain what they have said." By the end of January, all the Stradbally Gardaí had been moved to Dublin and suspended from duty on half-pay.[1]:112 A warrant was obtained to allow interception of their mail, as O'Mara believed that they would contact each other about the case.[1]:56–57

Whelan's pub

Testimony of Jim Fitzgerald

Further contradictions soon arose. Two Kilmacthomas villagers claimed that Patrick Whelan, the publican of Whelan's, told them that Larry had been in the pub on Christmas night. Whelan later told Griffin's wife and the Gardaí the exact opposite – not only had Larry not been in the pub, but nobody had visited the pub on Christmas Day. A further two villagers claimed that they had been drinking in Whelan's on Christmas night. They also said they had seen Cissie Whelan in the pub that evening, further contradicting Garda Dullea's statement. However, neither of them had seen Larry there as they had stayed in the kitchen, and not in the lounge area.[1]:58–62

On 23 January 1930 two local men were interviewed at the Garda station: Jim Fitzgerald and Thomas Corbett, both labourers.[1]:63–64 Fitzgerald's testimony painted the first clear picture of what became of Larry Griffin. On Christmas Day, Fitzgerald, Corbett, and two others entered Whelan's by the back gate. They went into the kitchen and were served drinks by Cissie Whelan. Upon hearing singing in the bar, Fitzgerald went out to the yard, looked through the bar window, and saw Gardaí Dullea and Murphy, Cissie Whelan, and several others inside. He entered the bar. At some point, some money fell out of Griffin's pocket. It was picked up by Ned Morrissey, who decided to keep it for himself. When Griffin demanded his money back, Morrissey purposely tripped Griffin, who fell and hit his head on a stove. The blow killed him.

Whelan feared that Griffin's death would ruin him and his business. Morrissey suggested that they dispose of Larry's body and cover up his death. According to Fitzgerald, Gardaí Dullea and Murphy, all the Whelan family, Thomas Cashin, headteacher of a local national school, and four other people (Ned Dunphy, Jack Galvin, and George and Patrick Cummins) were privy to this conversation. Cashin, Morrissey, George Cummins, and Patrick Whelan put Griffin's body in Cashin's car, which was the only car in the village, and drove away. Dullea and Murphy took Larry's bicycle, saying they would leave it on the Five Cross Road somewhere. Fitzgerald did not know where they eventually disposed of the body, but thought that they planned to drop it down a mine shaft.[1]:64–69 :82

Fitzgerald's statement was denied by everyone he had claimed was in the bar. Fitzgerald later asked to remain with the Gardaí as he was afraid to go home. He was taken into protective custody in Waterford.[1]:70–71

While Corbett agreed that he and Fitzgerald had gone to Whelan's on Christmas Day, he told a completely different story about what had happened after that. He said that they had not been admitted to Whelan's, and had instead gone to O'Reilly's, another pub in the village, and then to a house known as "The Hall" to play cards, where he claimed he fought with another local man.[1]:26 While it was unanimously agreed that a fight had occurred at the card game, the rest of Corbett's story was only partially corroborated by other witnesses.[1]:71–77

Gathering evidence

Copper mining had been a major industry in the area between 1827 and 1877, and there were many abandoned mineshafts nearby. Several were searched using grappling hooks and dredging appparatus. The possibility of sending down a diver was explored but it was dismissed as being too dangerous. Sightseers poured in to watch, as well as members of the press. The dredge turned up nothing more than the bodies of several pigs, goats, and dogs.[1]:95–102; 157–159 Additional searching saw the foreshore at Stradbally Cove being excavated to a depth of four feet, while local farmers and labourers searched nearby marshland.[1]:156 The garden of George Cummins was searched as were the grounds of a local convent and a pond in the grounds of a local estate.[1]:171 Recent burials in a local graveyard were exhumed.[1]:149–150 Despite this extensive searching, no trace of Larry Griffin was found.

The stove in Whelan's against which Griffin had allegedly hit his head was removed by Gardaí, as well as a wooden bench, ladies stockings, and a coal scuttle which appeared to be bloodstained. Other items were also taken from the houses of Thomas Cashin, Ned Morrissey, and George Cummins. Thomas Cashin's car was also taken.[1]:89–93

Interrogations

There is evidence that the Stradbally Gardaí were assaulted while being questioned.[1]:112 Garda Frawley's wife gave a statement in which she said that Garda Dullea had asked her on 7 January not to mention that he had been with Larry at Frawley's on Christmas Day.[1]:114 Garda Sullivan made a statement on 1 February admitting that he and Garda Frawley had been drinking in Whelan's pub, O'Reilly's pub, and Frawleys' flat on Christmas Day, and that he had gone to bed at about 4pm to sleep off the effects of alcohol. He awoke at 12:30am to hear Gardaí Dullea and Murphy return.[1]:112–119 Thomas Cashin was never interviewed, but his wife gave police a statement which provided him with an alibi for the whole of Christmas Day [1]:82–83 Various people who admitted to being in Whelan's on Christmas evening denied seeing Larry Griffin there. Many others were questioned but no more concrete evidence was obtained about what had happened to Larry.[1]:123–126

Trial

Arrests

On the morning of 24 January, Gardaí arrested Thomas Cashin and Ned Morrissey. They were charged with murder, disposing of a body with intent to obstruct a coroner's inquest, and taking away a postbag and postman's cap, which were property of the postmaster general.[1]:79–81 On 26 January, Patrick Whelan, George Cummins, and Patrick Cunningham were arrested and charged. This was followed by the arrests of Bridget Whelan and her daughter and son, Nora and James.[1]:90:99 All eight were held in Waterford and were remanded in custody on 31 January.[1]:99 On 3 February, Gardaí Dullea and Murphy were arrested and charged.[1]:120

Court proceedings

On 7 February, a preliminary hearing was held at Waterford courthouse, where the prosecution had to show that there was sufficient evidence to justify trying the defendants before a jury.[1]:131 With the ever-changing witness narrative and lack of hard evidence, the prosecution's case was to lean heavily on Jim Fitzgerald's testimony. However, when Fitzgerald was called to give evidence, he told a different story to the one he gave to Gardaí. He said that he, Thomas Corbett, and two other men were outside Whelan's and had drink handed out to them. Following this, he went on to O'Reillys, and then went to play cards. He then went back to Whelan's, which he stood outside for a while, before going home. When the prosecuting barrister challenged him about the difference between his statement and his current testimony, he said that he "may have told some lies in it." When questioned further, he said he could not say which parts were true and which were lies. The judge also questioned him but got no further. The prosecuting counsel asked for a week's remand which was granted by the judge.[1]:144

On 14 February, the prisoners were again brought to court. The two Kilmacthomas villagers told the court that Patrick Whelan had told them that Larry had been in the pub on Christmas night, that he had been very drunk, and that Whelan had tried unsuccessfully to persuade him to stay the night.[1]:152–3 A pathologist gave evidence about the items taken from various places, but the only ones which he could be certain that had human blood on them were sanitary items belonging to the young women in the Whelan household. The judge gave the prosecution another week to make its case, and the defendants were again remanded in custody.[1]:155

Another hearing was held on 21 February. Mrs. Frawley gave evidence saying that Garda Dullea and a drunken Larry Griffin had been in her house on Christmas Day, and that Garda Dullea had asked her not to say that she had seen him with Larry on that day. Another witness said that he had seen Garda Dullea and Larry walk around the corner at Whelan's. A further remand of one week was granted.[1]:162

On 1 March, no new evidence was produced, but the prosecution insisted that they were close to finding Griffin's body. The defendants were remanded in custody for another week.[1]:162

On 7 March, the prosecuting counsel said that further inquiries were to be made, but that he was now asking for the charges to be withdrawn. The defendants were released, to an outburst of cheering from their friends and supporters.[1]:174–176 Charges were never reinstated, and the case never went to trial again.

Aftermath

Litigation by Tommy Corbett

In February 1930, lawyers acting on Tommy Corbett's behalf issued summonses to four of the Gardaí who questioned him in February 1929, claiming damages for false imprisonment, assault, and threats of murder. The case was heard in December 1930; it was alleged that the Gardaí had tried to bribe him to say that he was in Whelan's pub on Christmas night, and that when he would not do so, they threatened to kill him. Corbett claimed the Gardaí then drove him to the nearby cliffs and threatened to throw him into the sea, and that one of the Gardaí put a revolver in his mouth and threatened to shoot him. The defendants denied the allegations, but the jury ruled in Corbett's favour. He was awarded £500 in damages and £500 in costs.[1]:186–200

The Gardaí involved were offered a choice between resignation and dismissal; all chose the former. Now jobless, they were unable to pay the £1000 to Corbett and began negotiating with him. Unease began to spread among the Whelans and Cashins, who appeared to be concerned that Corbett would make a deal which would involve him revealing what he knew about what had happened to Larry Griffin in exchange for the cash.[1]:194–195 A villager told a Stradbally Guard that he believed that Whelan, Cashin and company wanted "to close his (Tommy's) mouth" because they thought he was "capable of anything".[1]:195–197

Corbett's solicitor eventually bought out Corbett's damages claim for £125 on the condition that he had nothing more to do with the ex-Gardaí. This was met with widespread celebrations in Stradbally: Thomas Cashin took Corbett and his wife to Whelan's to celebrate. The Cunninghams and other ex-defendants visited the Corbetts that night with whiskey and stout.[1]:198–200

Litigation by the Whelan Family

In July 1930, the Whelan family were awarded £1740 in damages from Waterford News Ltd. because their newspaper, the Evening News, had published a report on 6 February 1929 about Larry's Griffin's disappearance which they claimed clearly implicated them in the matter. They later received damages from the Cork Examiner for a similar article.[1]:241–243

Litigation by Gardaí Murphy and Sullivan

In 1954, Gardaí Murphy and Sullivan sued a British newspaper, Empire News, for libel for a sum of £600 each over an article which said that "the postman was taken to the police barracks for safety. During the night, he left the room. There was no banister to the stairs. He stepped out into space and crashed to his death." The case was settled and the plaintiffs received undisclosed damages.[1]:258–9

Litigation by Thomas Cashin, James Whelan, Nora Opren (nee Whelan), and George Cummins

In 1974, Thomas Cashin, James Whelan, Nora Opren (née Whelan), and George Cummins took libel action against the Waterford News & Star over a review of a play which was based on Griffin's disappearance. They claimed that they had faced hatred, ridicule, and contempt because of the article. The case was settled for an undisclosed sum and the paper apologised to the plaintiffs.[1]:262

Litigation by James Whelan and Nora Opren (nee Whelan)

In the 1960s, Superintendent O'Mara sent a statement to the Irish Times with his account of the missing postman case, hoping that it would be published. It went unpublished due to fear of legal action. However, in 1977 an Irish Times correspondent came across the statement and wrote a long feature based on it. The Irish Times then received a letter from a solicitor acting on behalf of James Whelan and Nora Opren (née Whelan), saying that they intended to sue the paper for libel. The matter was settled out of court when the Irish Times were advised that the plaintiffs were likely to be awarded substantial damages by a court.[1]:262–264

The Griffin Family

A fund was set up which raised over £200 for the Griffin family. There was a huge response to the appeal, especially from post office staff all over Ireland, but very few contributions from Stradbally itself. Mary Griffin died in 1958, and is buried in the Griffin family plot. Larry is commemorated on her headstone.[1]:268–273

Jim Fitzgerald

Jim Fitzgerald returned to Stradbally in a Garda car after his appearance in court on 7 February.[1]:147–9 Superintendent Hunt, another Garda who had been brought into the investigation, reported that he had interviewed Fitzgerald after the collapse of the prosecution case and said that he was terrified, that he had been threatened repeatedly, and could not obtain any work. Hunt organised for him to be employed by a farmer in Galway. Fitzgerald left Stradbally in March 1930.

Hunt interviewed Fitzgerald again in Galway, who now claimed he had been in Whelan's between 7:30pm and 8pm on Christmas night. He said that he saw Garda Dullea and Larry Griffin there at about 8pm. He left Whelan's shortly afterward and met up with Tommy Corbett and Patrick Cunningham. They then moved on to O'Reilly's pub, and after that to a card game where Tommy Corbett and another man fought. After that, he went home with Tommy Corbett, while Patrick Cunningham went off in a different direction. Fitzgerald told Hunt that he had got his initial story about Larry's death secondhand from Tommy Corbett, who had heard it from his employer Patrick Cunningham. It was in fact Cunningham who had gone on to Whelan's on Christmas night and witnessed the events there.[1]:178–181

Fitzgerald died in a home for the elderly poor in Waterford in 1961.[1]:273–4

The Whelan Family

At the time of Griffin's disappearance, the Whelans were in arrears with their landlord, and had been successfully sued by one of their suppliers for non-payment for goods supplied. They were able to keep the business afloat with the money they made from the various libel actions that they won and also with a loan from Thomas Cashin.[1]:23 Patrick Whelan died in 1946, and his wife Bridget died in 1961. His son, James inherited the pub, and when he died in 1997, his son took it over. He still runs it today. Nora died in 1987, and Cissie in 2004.[1]:275–6

Thomas Cashin

Thomas Cashin had been the head teacher at the Ballylaneen national school for some years. Inspectors' reports on his work for the previous four years had rated him as non-efficient. He did not have an Irish language qualification and had failed the examination in 1924, 1925 and 1926 and 1928, and didn't turn up for the examination in 1927 and 1929. In May 1928, he was warned that serious action would be taken if matters did not improve.[1] :85[3] When he was charged with murder, he was suspended without pay. For reasons which have never been explained, he was not interviewed by the Gardaí at any time. When the case was dropped, the Department of Education wrote to him asking him to respond to allegations that he had been in a pub on Christmas Day, that he had been involved in the killing of Larry Griffin, and that his car had been used to dispose of the body. He vehemently denied all the allegations, expressing outrage that he should be accused of such offences. The Department of Education also sought information from the Gardaí who responded saying that they were convinced of his guilt, but the Department eventually accepted that there was no chance of this being proved in court. Cashin was reinstated in December 1930. He was later paid in full for the time he was suspended.[1]:226–238 He died in 1976.[1]:277

Attitudes in Stradbally

In 1986, Breandan Ó'hEither, a journalist and broadcaster, passed through Stradbally. He was recognised by a man in the street, and when passing Whelan's, said to the man, "was it upstairs or downstairs it happened?" The man replied, "I think it might be a good idea if you fuck off out of here".[1]:265 In the early 1990s, the broadcaster, Cathal Ó'Shannon tried to make a TV programme about the case, but RTÉ turned it down because James Whelan was still alive and likely to sue for libel. Ó'Shannon reported that he "was almost run out of Stradbally and received two threats of legal action from the Whelan family" while researching the case.[1]:267

In media

Tadgh Ó Dúshlaine has written an unpublished account of the case. He requested access to Garda files many times without success.[1]:267

On 14 September 2009, RTE broadcast CSÍ - The Missing Postman.[5][6][7] The program was researched by Fachtna Ó Drisceoil and Tadgh Ó Dúshlaine and drew on original witness statements from the National Archives, particularly that of Jim Fitzgerald.

A few days before the broadcast, the Garda Commissioner announced that all the files on the case would be made available. There were 5000-10000 pages in the file, but no physical evidence which might have provided DNA. Information from these files was incorporated into the 2011 book The Missing Postman by Fachtna Ó Drisceoil.[1] Ó Drisceoil concludes that the Gardaí at the time failed to cross-check Jim Fitzgerald's statement with other witness statements which would have strongly indicated that he was not in Whelan's when he said he was. Ó Drisceoil believes that the statement taken by Superintendent Hunt from Fitzgerald after he moved to Galway is more accurate than the first one, and that Fitzgerald did indeed get a secondhand account of what happened from Tommy Corbett, who had heard it from Patrick Cunningham. Ó Drisceoil believes that there was an altercation in Whelan's involving Larry Griffin, in which he was either killed outright or injured and taken across the road to the Garda barracks, where he later stumbled out of bed and fell down the stairs to his death. The people involved decided to cover up his death to protect their jobs and positions of power. Patrick Whelan was already in financial difficulty and losing his licence would have been a disaster. Cashin and the two Gardaí, Dullea and Murphy, would have lost their jobs if it was found that they had been drinking illegally.

See also

References

- Ó Drisceoil, Fachtna (2011). The Missing Postman. Cork: Mercier Press. ISBN 978 1 85635 693 0.

- War Office and Air Ministry: Service Medal and Award Rolls, First World War. WO329. The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England

- Department of Education General Registry files, File 13001 Box 252 and File 27034 Box 614, National Archives of Ireland

- "Mystery still surrounds 1929 disappearance of Co Waterford postman". The Irish Times. Dublin. 27 December 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- CSI - The Missing Postman: part 1 on YouTube

- CSI - The Missing Postman: part 2 on YouTube

- CSI - The Missing Postman: part 3 on YouTube