Domus Tiberiana

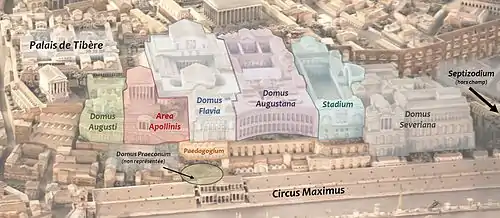

The Domus Tiberiana was an Imperial Roman palace in ancient Rome, located on the northwest corner of the Palatine Hill. It probably takes its name from a house built by the Emperor Tiberius, who is known to have lived on the Palatine, though no sources mention his having built a residence.[1] It was enlarged by the successors to Tiberius, and would have been the principal Roman residence of Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero during the early part of his reign.[2] Relatively little is known of the structure archaeologically, since the Farnese Gardens have occupied the site of the main level since the 16th century, making excavation difficult.[3]

| Domus Tiberiana | |

|---|---|

Domus Tiberiana in the upper left hand corner | |

| Location | Palatine Hill |

| Type of structure | Domus |

| Related | List of ancient monuments in Rome |

| |

Description

.jpg.webp)

The remains of the Domus Tiberiana lie on the northwest corner of the Palatine, facing the Velabrum and the Forum Romanum below, with the Capitoline hill beyond. The site comprises an area of approximately 150 metres by 120 metres (492 x 394 feet),[4] and is occupied by the platform of the Farnese Gardens, which were constructed in 1550 by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese. The visible remains are those of the imposing arcaded support structures on the northern slope of the hill, built under Domitian, Trajan and Hadrian.[5] On the level of the forum the ruins of a vestibule complex, begun by Domitian and completed by Hadrian, lie behind the Temple of Castor and Pollux. From here there was an access ramp which led up the slope of the hill to the Domus Tiberiana on the summit.[6]

The core of the Tiberiana was oriented around a large peristyle with arcades surrounding it on four sides. A double block of rooms separated by a broad corridor was built south of this peristyle, and another block of rooms stood to the north.[7] Along the east side of the Tiberiana is a 130 meter (427 foot) long cryptoporticus from the time of Nero, with mosaic floors and poorly preserved frescoes. This cryptoporticus was connected to the Flavian Palace when it was built. In the southeast corner of the palace, close to the Domus Livia, are the remains of an elliptical basin probably used as a fishpond.[8] On the southwest front is a portico fronting a series of rooms, which are believed to have housed the Praetorian Guard based on the graffiti found in them.[9]

Building History

Early Empire

Scholarly consensus holds that Tiberius built a splendid house as princeps, which would form the base structure for a complex of buildings developed by his successors Caligula, Claudius and Nero.[10] It's possible that Tiberius built his house on the site of his father's house, and the place of his birth, since excavations have revealed an earlier Republican-era house built on a high podium beneath the western end of the Tiberiana.[11]

The name Domus Tiberiana first appears in the Histories of Tacitus in connection with the assassination of Galba in 69 AD.[12] However, earlier references to the houses of Caligula, Claudius and Nero on the Palatine by authors like Suetonius and Plutarch accord with the location of the Domus Tiberiana, making it likely these were one and the same house.[13] Suetonius mentions that Caligula expanded the palace out into the Forum, where he converted the Temple of Castor and Pollux into an entry vestibule.[14] Although only scant traces have been left of this extension, the remains of masonry and a large rectangular pool measuring 9m x 26m (30 feet x 85 feet) lying within a court can be discerned behind the Temple of Castor and Pollux.[15]

The cluster of buildings which evolved between Tiberius and Nero were badly damaged in the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, after which Nero remodeled the palace and incorporated it into his Domus Aurea, an immense network of buildings stretching from the Esquiline Hill west to the Palatine, where it terminated at the Domus Tiberiana. Part of the rebuilding involved constructing a buttressed perimeter wall which enclosed the assorted houses for the first time.[16] The Neronian building was badly damaged by another fire in 80 AD. Domitian undertook the grandest building program of any emperor on the Palatine, restoring and enlarging the Domus Tiberiana and incorporating it as an annex to his primary new residence, the Palace of Domitian (known as the Domus Augustana in antiquity).[17][18] Domitian created a long loggia with a marble parapet, carrying the building to the edge of the Clivus Victoriae. He also rebuilt the vestibule behind the Temple of Castor and Pollux, changing its orientation. There was a huge entrance hall just behind the temple and on the same axis with it. Next to it, to the east, was a structure which has been identified as the guards quarters, later converted into the church of Santa Maria Antiqua.[19][20] The third component of the vestibule was a triple ramp leading up the hillside to the Clivus Victoriae and the Domus Tiberiana above.[21]

Trajan and Hadrian made further alterations and extensions to the Tiberiana. Under Hadrian, the substructures were expanded further over the northern slope of the hill, covering the Republican-era Clivus Victoriae, a road which passed midway along the hillside, and reaching the Via Nova, a Neronian road built alongside the Via Sacra.[22][23] The piers supported arcaded galleries, upon which rested the expanded main floor of the palace on the summit of the hill.

Later History

The Domus Tiberiana was apparently favored by the Antonine Emperors, who are mentioned in the sources as having resided there.[24] Coarelli suggested that it was used to house the designated-heir to the ruling emperor, since both Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius lived there after they were adopted by Antoninus Pius.[25] The ruling emperor would have lived in the Augustana - thus the names Tiberiana and Augustana evoked Rome's first emperor and his designated heir. A library was housed in the Tiberiana, which contained the imperial archives and probably served as the replacement for the libraries of Augustus's Temple of Apollo, which burned in AD 80.[26] The Tiberiana was gutted in a major fire under Commodus, which destroyed the archives of the library. It was restored again, and survived as an official residence after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, passing through the hands of the powers which occupied Rome successively from the 5th to the 8th centuries. Pope John VII, whose father had been the curator of the imperial palaces on the Palatine, lived in the Tiberiana in the 8th century.[27]

During the medieval era, the palace was abandoned and fell into ruins. It suffered severe material theft during the middle ages, and was being used as an orchard when Alessandro Farnese decided to convert the property to a grand formal garden, the first private botanical garden in Europe. The first excavations were undertaken in 1728, which uncovered a great many architectural fragments. Pietro Rosa undertook excavations in the 1860s which uncovered the substructures on the north side of the hill and the central peristyle of the piano nobile.[28][29][30]

Art works

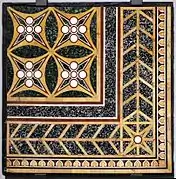

Various sculptures and architectural ornaments have been discovered on or near the site of the Domus Tiberiana. These include a pair of white marble wings that would have belonged to a large Nike statue, and a statue of Aphrodite.[31][32] A high quality panel of opus sectile flooring, composed of several types of marble inlaid in a geometric pattern, was found during the excavations of Pietro Rosa and is on display in the Palatine Museum, along with the statues discovered at the site.[33] Significant finds have been made within the Hadrianic arcades which covered the old Clivus Victoriae, including altars to Minerva and Lucina. Several fragments of high-quality terracotta statues were also found within these arcades; they are believed to have been working models for making copies of Greek statues for Roman clients in the time of Caesar and Augustus.[34]

Marble wings from a Nike statue

Marble wings from a Nike statue Panel of marble flooring from the Tiberiana

Panel of marble flooring from the Tiberiana A headless statue of Aphrodite Charis from the Tiberiana

A headless statue of Aphrodite Charis from the Tiberiana Fragment of a terracotta head from the Caesarean or Augustan age

Fragment of a terracotta head from the Caesarean or Augustan age Another fragmentary terracotta head

Another fragmentary terracotta head

Bibliography

- Andrea Carandini (2017). Atlas of Ancient Rome. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16347-5.

- Filippo Coarelli (2014). Rome and Environs: An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28209-4.

- Samuel Ball Platner & Thomas Ashby (1929). A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lawrence Richardson Jr. (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4300-6.

- Maria Antonietta Tomei (1998). Soprintendenza Archeologica Di Roma: The Palatine. Milan: Electa.

- J.B. Ward-Perkins (1994). Roman Imperial Architecture. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05292-8.

References

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- Peter Aicher (2004). "Rome Alive: A Source Guide to the Ancient City". Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers.

- "Domus Tiberiana". University of Virginia. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- J.B. Ward-Perkins, 1994; p. 83-84

- Richardson, 1992; p. 136-137

- Tomei, 1998; p. 41

- Richardson, 1992; p. 137

- Carandini, 2017; p. 236

- Coarelli, 2014; p. 144

- Platner & Ashby, 1929; p. 192

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- Suetonius, Caligula 22.1-4

- Richardson, 1992; p. 137

- Tomei, 1998; p. 40

- Coarelli, 2014; p. 144

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- Richardson, 1992; p. 137

- Ward-Perkins, 1994; p. 83

- Ward-Perkins, 1994; p. 83-84

- Richardson, 1992; p. 137

- Tomei, 1998; p. 41-42

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- Coarelli, 2014; p. 144

- Coarelli, 2014; p. 144

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- Tomei, 1998; p. 39

- Coarelli, 2014; p. 144-145

- Richardson, 1992; p. 137

- "LARGE WINGS IN WHITE GREEK MARBLE". Parco archeologico del Colosseo. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- "Statue of Aphrodite Charis". Parco archeologico del Colosseo. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- "Panel with Opus Sectile". Parco archeologico del Colosseo. Retrieved 2021-01-18.

- Tomei, 1998; p. 41-42