Drilling rig

A drilling rig is an integrated system that drills wells, such as oil or water wells, in the earth's subsurface. Drilling rigs can be massive structures housing equipment used to drill water wells, oil wells, or natural gas extraction wells, or they can be small enough to be moved manually by one person and such are called augers. Drilling rigs can sample subsurface mineral deposits, test rock, soil and groundwater physical properties, and also can be used to install sub-surface fabrications, such as underground utilities, instrumentation, tunnels or wells. Drilling rigs can be mobile equipment mounted on trucks, tracks or trailers, or more permanent land or marine-based structures (such as oil platforms, commonly called 'offshore oil rigs' even if they don't contain a drilling rig). The term "rig" therefore generally refers to the complex equipment that is used to penetrate the surface of the Earth's crust.

Small to medium-sized drilling rigs are mobile, such as those used in mineral exploration drilling, blast-hole, water wells and environmental investigations. Larger rigs are capable of drilling through thousands of metres of the Earth's crust, using large "mud pumps" to circulate drilling mud (slurry) through the drill bit and up the casing annulus, for cooling and removing the "cuttings" while a well is drilled. Hoists in the rig can lift hundreds of tons of pipe. Other equipment can force acid or sand into reservoirs to facilitate extraction of the oil or natural gas; and in remote locations there can be permanent living accommodation and catering for crews (which may be more than a hundred). Marine rigs may operate thousands of miles distant from the supply base with infrequent crew rotation or cycle.

History

Until internal combustion engines were developed in the late 19th century, the main method for drilling rock was muscle power of man or animal. The technique of oil drilling through percussion or rotary drilling has its origins dating back to the ancient Chinese Han Dynasty in 100 BC, where percussion drilling was used to extract natural gas in the Sichuan province.[1] Early oil and gas drilling methods were seemingly primitive as it required several technical skills.[1][2] The skills involved the availability of heavy iron bits and long bamboo poles, the manufacturing of long and sturdy cables woven from bamboo fiber, and levers. Heavy iron bits were attached to long bamboo cables suspended from bamboo derricks and then were repeatedly raised and dropped into a manually dug hole by having two to six men jumping on a lever.[1] Han dynasty oil wells made by percussion drilling was effective but only reached 10 meters deep and 100 meters by the 10th century.[1] By the 16th century, the Chinese were exploring and drilling oil wells more than 2000 feet deep.[2] A modernized variant of the ancient Chinese drilling technique was used by American businessman Edwin Drake to drill Pennsylvania's first oil well in 1859 using small steam engines to power the drilling process rather than by human muscle.[1]

In the 1970s, outside of the oil and gas industry, roller bits using mud circulation were replaced by the first pneumatic reciprocating piston Reverse Circulation (RC) drills, and became essentially obsolete for most shallow drilling, and are now only used in certain situations where rocks preclude other methods. RC drilling proved much faster and more efficient, and continues to improve with better metallurgy, deriving harder, more durable bits, and compressors delivering higher air pressures at higher volumes, enabling deeper and faster penetration. Diamond drilling has remained essentially unchanged since its inception.

Petroleum drilling industry

Oil and natural gas drilling rigs are used not only to identify geologic reservoirs but also to create holes that allow the extraction of oil or natural gas from those reservoirs. Primarily in onshore oil and gas fields once a well has been drilled, the drilling rig will be moved off of the well and a service rig (a smaller rig) that is purpose-built for completions will be moved on to the well to get the well on line.[3] This frees up the drilling rig to drill another hole and streamlines the operation as well as allowing for specialization of certain services, i.e. completions vs. drilling.

Mining drilling industry

Mining drilling rigs are used for two main purposes, exploration drilling which aims to identify the location and quality of a mineral, and production drilling, used in the production-cycle for mining. Drilling rigs used for rock blasting for surface mines vary in size dependent on the size of the hole desired, and is typically classified into smaller pre-split and larger production holes. Underground mining (hard rock) uses a variety of drill rigs dependent on the desired purpose, such as production, bolting, cabling, and tunnelling.

Mobile drilling rigs

.jpg.webp)

In early oil exploration, drilling rigs were semi-permanent in nature and the derricks were often built on site and left in place after the completion of the well. In more recent times drilling rigs are expensive custom-built machines that can be moved from well to well. Some light duty drilling rigs are like a mobile crane and are more usually used to drill water wells. Larger land rigs must be broken apart into sections and loads to move to a new place, a process which can often take weeks.

Small mobile drilling rigs are also used to drill or bore piles. Rigs can range from 100 short tons (91,000 kg) continuous flight auger (CFA) rigs to small air powered rigs used to drill holes in quarries, etc. These rigs use the same technology and equipment as the oil drilling rigs, just on a smaller scale.

The drilling mechanisms outlined below differ mechanically in terms of the machinery used, but also in terms of the method by which drill cuttings are removed from the cutting face of the drill and returned to surface.

Drilling rig classification

There are many types and designs of drilling rigs. Many drilling rigs are capable of switching or combining different drilling technologies as needed. Drilling rigs can be described using any of the following attributes:

By power used

- Mechanical — the rig uses torque converters, clutches, and transmissions powered by its own engines, often diesel.

- Electric — the major items of machinery are driven by electric motors, usually with power generated on-site using internal combustion engines.

- Hydraulic — the rig primarily uses hydraulic power.

- Pneumatic — the rig is primarily powered by pressurized air.

- Steam — the rig uses steam-powered engines and pumps (obsolete after middle of 20th century.).

By pipe used

- Cable — a braided hemp or wire rope is used to raise and drop the drill bit.

- Conventional — uses metal or plastic drill pipe of varying types.

- Coil tubing — uses a single flexible tube of sufficient length, stored on a drum up to five metres in diameter, and a downhole drilling motor.

- Chain — a chain is used to raise and drop the drill bit in some hydraulic rigs.

By height

Rigs are differentiated by height based on how many connected joints of drill pipe they are able to "stand" in the derrick when it is out of the hole. Typically this is done when changing a drill bit or when "logging" the well. A single joint of pipe is typically some 30 feet long.

- Single — can hold only single drill pipes. The presence or absence of vertical pipe racking "fingers" varies from rig to rig.

- Double — derrick can hold two connected drill pipes, called a "double stand" or simply a "double".

- Triple — derrick can hold three connected drill pipes: a "triple stand" or "thribble".

- Qua — can hold four connected drill pipes, called a "quad stand" or "fourble". Derricks of this size are uncommon on land based operations, but utilized in offshore drilling.

By method of rotation or drilling method

- No-rotation includes direct push rigs and most service rigs.

- Rotary table — rotation is achieved by turning a square or hexagonal pipe (the "Kelly") in a rotary table at drill floor level.

- Top drive — rotation and circulation is done at the top of the drill string, on a motor that moves in a track along the derrick. This is the design of the most modern rigs.

- Sonic — uses primarily vibratory energy to advance the drill string.

- Hammer — uses rotation and percussive force (see Down-the-hole drill).

By position of derrick

Directional drilling

Directional drilling is done with a mud motor on the bottom hole assembly. The direction is controlled by a wireless controller to drill the hole in any way that the driller requires.

Drilling techniques

There are a variety of drilling techniques which can be used to drill a borehole into the ground. Each has its advantages and disadvantages, in terms of the depth to what it can drill, the type of sample returned, the costs involved and penetration rates achieved. Some types included are rotary cut, rotary Abrasive, rotary reverse, cable tooling, and sonic drilling.

Auger drilling

Auger drilling is done with a helical screw which is driven into the ground with rotation; the earth is lifted up the borehole by the blade of the screw. Hollow stem auger drilling is used for softer ground such as swamps where the hole will not stay open by itself for environmental drilling, geotechnical drilling, soil engineering and geochemistry reconnaissance work in exploration for mineral deposits. Solid flight augers/bucket augers are used in harder ground construction drilling. In some cases, mine shafts are dug with auger drills. Small augers can be mounted on the back of a utility truck, with large augers used for sinking piles for bridge foundations.

Auger drilling is restricted to soil, soft unconsolidated formations, or weak weathered rock. It is cheap and fast.

Percussion rotary air blast drilling

RAB drilling is used most frequently in the mineral exploration industry. (This tool is also known as a Down-the-hole drill.) The drill uses a pneumatic reciprocating piston-driven "hammer" to energetically drive a heavy drill bit into the rock. The drill bit is hollow, solid steel and has ~20 mm thick tungsten rods protruding from the steel matrix as "buttons". The tungsten buttons are the cutting face of the bit.

The cuttings are blown up the outside of the rods and collected at surface. Air or a combination of air and foam lift the cuttings.

RAB drilling is used primarily for mineral exploration, water bore drilling and blast-hole drilling in mines, as well as for other applications such as engineering, etc. RAB produces lower quality samples because the cuttings are blown up the outside of the rods and can be contaminated from contact with other rocks. RAB drilling at extreme depth, if it encounters water, may rapidly clog the outside of the hole with debris, precluding removal of drill cuttings from the hole. This can be counteracted, however, with the use of "stabilizers" also known as "reamers", which are large cylindrical pieces of steel attached to the drill string, and made to perfectly fit the size of the hole being drilled. These have sets of rollers on the side, usually with tungsten buttons, that constantly break down cuttings being pushed upwards.

The use of high-powered air compressors, which push 900-1150 cfm of air at 300-350 psi down the hole also ensures drilling of a deeper hole up to ~1250 m due to higher air pressure which pushes all rock cuttings and any water to the surface. This, of course, is all dependent on the density and weight of the rock being drilled, and on how worn the drill bit is.

Air core drilling

Air core drilling and related methods use hardened steel or tungsten blades to bore a hole into unconsolidated ground. The drill bit has three blades arranged around the bit head, which cut the unconsolidated ground. The rods are hollow and contain an inner tube which sits inside the hollow outer rod barrel. The drill cuttings are removed by injection of compressed air into the hole via the annular area between the innertube and the drill rod. The cuttings are then blown back to surface up the inner tube where they pass through the sample separating system and are collected if needed. Drilling continues with the addition of rods to the top of the drill string. Air core drilling can occasionally produce small chunks of cored rock.

This method of drilling is used to drill the weathered regolith, as the drill rig and steel or tungsten blades cannot penetrate fresh rock. Where possible, air core drilling is preferred over RAB drilling as it provides a more representative sample. Air core drilling can achieve depths approaching 300 metres in good conditions. As the cuttings are removed inside the rods and are less prone to contamination compared to conventional drilling where the cuttings pass to the surface via outside return between the outside of the drill rod and the walls of the hole. This method is more costly and slower than RAB. This method of drilling was invented by Wallis Drilling a drilling company based in Perth, Western Australia.

Cable tool drilling

Cable tool rigs are a traditional way of drilling water wells. The majority of large diameter water supply wells, especially deep wells completed in bedrock aquifers, were completed using this drilling method. Although this drilling method has largely been supplanted in recent years by other, faster drilling techniques, it is still the most feasible drilling method for large diameter, deep bedrock wells, and in widespread use for small rural water supply wells. The impact of the drill bit fractures the rock and in many shale rock situations increases the water flow into a well over rotary.

Also known as ballistic well drilling and sometimes called "spudders", these rigs raise and drop a drill string with a heavy carbide tipped drilling bit that chisels through the rock by finely pulverizing the subsurface materials. The drill string is composed of the upper drill rods, a set of "jars" (inter-locking "sliders" that help transmit additional energy to the drill bit and assist in removing the bit if it is stuck) and the drill bit. During the drilling process, the drill string is periodically removed from the borehole and a bailer is lowered to collect the drill cuttings (rock fragments, soil, etc.). The bailer is a bucket-like tool with a trapdoor in the base. If the borehole is dry, water is added so that the drill cuttings will flow into the bailer. When lifted, the trapdoor closes and the cuttings are then raised and removed. Since the drill string must be raised and lowered to advance the boring, the casing (larger diameter outer piping) is typically used to hold back upper soil materials and stabilize the borehole.

Cable tool rigs are simpler and cheaper than similarly sized rotary rigs, although loud and very slow to operate. The world record cable tool well was drilled in New York to a depth of almost 12,000 feet (3,700 m). The common Bucyrus-Erie 22 can drill down to about 1,100 feet (340 m). Since cable tool drilling does not use air to eject the drilling chips like a rotary, instead using a cable strung bailer, technically there is no limitation on depth.

Cable tool rigs now are nearly obsolete in the United States. They are mostly used in Africa or Third-World countries. Being slow, cable tool rig drilling means increased wages for drillers. In the United States drilling wages would average around US$200 per day per man, while in Africa it is only US$6 per day per man, so a slow drilling machine can still be used in undeveloped countries with depressed wages. A cable tool rig can drill 25 feet (7.6 m) to 60 feet (18 m) of hard rock a day. A newer rotary drillcat top head rig equipped with down-the-hole (DTH) hammer can drill 500 feet (150 m) or more per day, depending on size and formation hardness.

Reverse circulation drilling

Reverse circulation drilling (RC) is similar to air core drilling, in that the drill cuttings are returned to surface inside the rods. The drilling mechanism is a pneumatic reciprocating piston known as a "hammer" driving a tungsten-steel drill bit. RC drilling utilises much larger rigs and machinery and depths of up to 500 metres (1,600 ft) are routinely achieved. RC drilling ideally produces dry rock chips, as large air compressors dry the rock out ahead of the advancing drill bit. RC drilling is slower and costlier but achieves better penetration than RAB or air core drilling; it is cheaper than diamond coring and is thus preferred for most mineral exploration work.

Reverse circulation is achieved by blowing air down the rods, the differential pressure creating air lift of the water and cuttings up the "inner tube", which is inside each rod. It reaches the "divertor" at the top of the hole, then moves through a sample hose which is attached to the top of the "cyclone". The drill cuttings travel around the inside of the cyclone until they fall through an opening at the bottom and are collected in a sample bag.

The most commonly used RC drill bits are 5-8 inches (13–20 cm) in diameter and have round tungsten 'buttons' that protrude from the bit, which are required to drill through shale and abrasive rock. As the buttons wear down, drilling becomes slower and the rod string can potentially become bogged in the hole. This is a problem as trying to recover the rods may take hours and in some cases weeks. The rods and drill bits themselves are very expensive, often resulting in great cost to drilling companies when equipment is lost down the bore hole. Most companies will regularly re-grind the buttons on their drill bits in order to prevent this, and to speed up progress. Usually, when something is lost (breaks off) in the hole, it is not the drill string, but rather from the bit, hammer, or stabilizer to the bottom of the drill string (bit). This is usually caused by operator error, over-stressed metal, or adverse drilling conditions causing downhole equipment to get stuck in a part of the hole.

Although RC drilling is air-powered, water is also used to reduce dust, keep the drill bit cool, and assist in pushing cutting back upwards, but also when "collaring" a new hole. A mud called "Liqui-Pol" is mixed with water and pumped into the rod string, down the hole. This helps to bring up the sample to the surface by making the sand stick together. Occasionally, "Super-Foam" (a.k.a. "Quik-Foam") is also used, to bring all the very fine cuttings to the surface, and to clean the hole. When the drill reaches hard rock, a "collar" is put down the hole around the rods, which is normally PVC piping. Occasionally the collar may be made from metal casing. Collaring a hole is needed to stop the walls from caving in and bogging the rod string at the top of the hole. Collars may be up to 60 metres deep, depending on the ground, although if drilling through hard rock a collar may not be necessary.

Reverse circulation rig setups usually consist of a support vehicle, an auxiliary vehicle, as well as the rig itself. The support vehicle, normally a truck, holds diesel and water tanks for resupplying the rig. It also holds other supplies needed for maintenance on the rig. The auxiliary is a vehicle, carrying an auxiliary engine and a booster engine. These engines are connected to the rig by high pressure air hoses. Although RC rigs have their own booster and compressor to generate air pressure, extra power is needed which usually isn't supplied by the rig due to lack of space for these large engines. Instead, the engines are mounted on the auxiliary vehicle. Compressors on an RC rig have an output of around 1000 cfm at 500 psi (500 L·s−1 at 3.4 MPa). Alternatively, stand-alone air compressors which have an output of 900-1150cfm at 300-350 psi each are used in sets of 2, 3, or 4, which are all routed to the rig through a multi-valve manifold.

Diamond core drilling

Diamond core drilling (exploration diamond drilling) uses an annular diamond-impregnated drill bit attached to the end of hollow drill rods to cut a cylindrical core of solid rock. The diamonds used to make diamond core bits are a variety of sizes, fine to microfine industrial grade diamonds, and the ratio of diamonds to metal used in the matrix affects the performance of the bits cutting ability in different types of rock formations. The diamonds are set within a matrix of varying hardness, from brass to high-grade steel. Matrix hardness, diamond size and dosing can be varied according to the rock which must be cut. The bits made with hard steel with a low diamond count are ideal for softer highly fractured rock while others made of softer steels and high diamond ratio are good for coring in hard solid rock. Holes within the bit allow water to be delivered to the cutting face. This provides three essential functions — lubrication, cooling, and removal of drill cuttings from the hole.

Diamond drilling is much slower than reverse circulation (RC) drilling due to the hardness of the ground being drilled. Drilling of 1200 to 1800 metres is common and at these depths, ground is mainly hard rock. Techniques vary among drill operators and what the rig they are using is capable of, some diamond rigs need to drill slowly to lengthen the life of drill bits and rods, which are very expensive and time consuming to replace at extremely deep depths. As a diamond drill rig cores deeper and deeper the time consuming part of the process is not cutting 5 to 10 more feet of rock core but the retrieval of the core with the wire line & overshot tool. Core samples are retrieved via the use of a core tube, a hollow tube placed inside the rod string and pumped with water until it locks into the core barrel. As the core is drilled, the core barrel slides over the core as it is cut. An "overshot" attached to the end of the winch cable is lowered inside the rod string and locks on to the backend (aka head assembly), located on the top end of the core barrel. The winch is retracted, pulling the core tube to the surface. The core does not drop out of the inside of the core tube when lifted because either a split ring core lifter or basket retainer allow the core to move into, but not back out of the tube.

Once the core tube is removed from the hole, the core sample is then removed from the core tube and catalogued. The Driller's assistant unscrews the backend off the core tube using tube wrenches, then each part of the tube is taken and the core is shaken out into core trays. The core is washed, measured and broken into smaller pieces using a hammer or sawn through to make it fit into the sample trays. Once catalogued, the core trays are retrieved by geologists who then analyse the core and determine if the drill site is a good location to expand future mining operations.

Diamond rigs can also be part of a multi-combination rig. Multi-combination rigs are a dual setup rig capable of operating in either a reverse circulation (RC) and diamond drilling role (though not at the same time). This is a common scenario where exploration drilling is being performed in a very isolated location. The rig is first set up to drill as an RC rig and once the desired metres are drilled, the rig is set up for diamond drilling. This way the deeper metres of the hole can be drilled without moving the rig and waiting for a diamond rig to set up on the pad.

Direct push rigs

Direct push technology includes several types of drilling rigs and drilling equipment which advances a drill string by pushing or hammering without rotating the drill string. While this does not meet the proper definition of drilling, it does achieve the same result — a borehole. Direct push rigs include both cone penetration testing (CPT) rigs and direct push sampling rigs such as a PowerProbe or Geoprobe. Direct push rigs typically are limited to drilling in unconsolidated soil materials and very soft rock.

CPT rigs advance specialized testing equipment (such as electronic cones), and soil samplers using large hydraulic rams. Most CPT rigs are heavily ballasted (20 metric tons is typical) as a counter force against the pushing force of the hydraulic rams which are often rated up to 20 kN. Alternatively, small, light CPT rigs and offshore CPT rigs will use anchors such as screwed-in ground anchors to create the reactive force. In ideal conditions, CPT rigs can achieve production rates of up to 250–300 meters per day.

Direct push drilling rigs use hydraulic cylinders and a hydraulic hammer in advancing a hollow core sampler to gather soil and groundwater samples. The speed and depth of penetration is largely dependent on the soil type, the size of the sampler, and the weight and power of the rig. Direct push techniques are generally limited to shallow soil sample recovery in unconsolidated soil materials. The advantage of direct push technology is that in the right soil type it can produce a large number of high quality samples quickly and cheaply, generally from 50 to 75 meters per day. Rather than hammering, direct push can also be combined with sonic (vibratory) methods to increase drill efficiency.

Hydraulic rotary drilling

Oil well drilling utilizes tri-cone roller, carbide embedded, fixed-cutter diamond, or diamond-impregnated drill bits to wear away at the cutting face. This is preferred because there is no need to return intact samples to surface for assay as the objective is to reach a formation containing oil or natural gas. Sizable machinery is used, enabling depths of several kilometres to be penetrated. Rotating hollow drill pipes carry down bentonite and barite infused drilling muds to lubricate, cool, and clean the drilling bit, control downhole pressures, stabilize the wall of the borehole and remove drill cuttings. The mud travels back to the surface around the outside of the drill pipe, called the annulus. Examining rock chips extracted from the mud is known as mud logging. Another form of well logging is electronic and is commonly employed to evaluate the existence of possible oil and gas deposits in the borehole. This can take place while the well is being drilled, using Measurement While Drilling tools, or after drilling, by lowering measurement tools into the newly drilled hole.

The rotary system of drilling was in general use in Texas in the early 1900s. It is a modification of one invented by Fauvelle in 1845, and used in the early years of the oil industry in some of the oil-producing countries in Europe.[4] Originally pressurized water was used instead of mud, and was almost useless in hard rock before the diamond cutting bit. The main breakthrough for rotary drilling came in 1901, when Anthony Francis Lucas combined the use of a steam-driven rig and of mud instead of water in the Spindletop discovery well.[5]

The drilling and production of oil and gas can pose a safety risk and a hazard to the environment from the ignition of the entrained gas causing dangerous fires and also from the risk of oil leakage polluting water, land and groundwater. For these reasons, redundant safety systems and highly trained personnel are required by law in all countries with significant production.

Automated drill rig

An automated drill rig (ADR) is an automated full-sized walking land-based drill rig that drills long lateral sections in horizontal wells for the oil and gas industry.[6] ADRs are agile rigs that can move from pad to pad to new well sites faster than other full-sized drilling rigs. Each rig costs about $25 million. ADR is used extensively in the Athabasca oil sands. According to the "Oil Patch Daily News", "Each rig will generate 50,000 man-hours of work during the construction phase and upon completion, each operating rig will directly and indirectly employ more than 100 workers." Compared to conventional drilling rigs", Ensign, an international oilfield services contractor based in Calgary, Alberta, that makes ADRs claims that they are "safer to operate, have "enhanced controls intelligence," "reduced environmental footprint, quick mobility and advanced communications between field and office."[6] In June 2005 the first specifically designed slant automated drilling rig (ADR), Ensign Rig No. 118, for steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) applications was mobilized by Deer Creek Energy Limited, a Calgary-based oilsands company.[7]

Limits of the technology

Drill technology has advanced steadily since the 19th century. However, there are several basic limiting factors which will determine the depth to which a bore hole can be sunk.

All holes must maintain outer diameter; the diameter of the hole must remain wider than the diameter of the rods or the rods cannot turn in the hole and progress cannot continue. Friction caused by the drilling operation will tend to reduce the outside diameter of the drill bit. This applies to all drilling methods, except that in diamond core drilling the use of thinner rods and casing may permit the hole to continue. Casing is simply a hollow sheath which protects the hole against collapse during drilling, and is made of metal or PVC. Often diamond holes will start off at a large diameter and when outside diameter is lost, thinner rods put down inside casing to continue, until finally the hole becomes too narrow. Alternatively, the hole can be reamed; this is the usual practice in oil well drilling where the hole size is maintained down to the next casing point.

For percussion techniques, the main limitation is air pressure. Air must be delivered to the piston at sufficient pressure to activate the reciprocating action, and in turn drive the head into the rock with sufficient strength to fracture and pulverise it. With depth, volume is added to the in-rod string, requiring larger compressors to achieve operational pressures. Secondly, groundwater is ubiquitous, and increases in pressure with depth in the ground. The air inside the rod string must be pressurised enough to overcome this water pressure at the bit face. Then, the air must be able to carry the rock fragments to surface. This is why depths in excess of 500 m for reverse circulation drilling are rarely achieved, because the cost is prohibitive and approaches the threshold at which diamond core drilling is more economic.

Diamond drilling can routinely achieve depths in excess of 1200 m. In cases where money is no issue, extreme depths have been achieved, because there is no requirement to overcome water pressure. However, water circulation must be maintained to return the drill cuttings to surface, and more importantly to maintain cooling and lubrication of the cutting surface of the bit; while at the same time reduce friction on the steel walls of the rods turning against the rock walls of the hole. When water return is lost the rods will vibrate, this is called "rod chatter", and that will damage the drill rods, and crack the joints.

Without sufficient lubrication and cooling, the matrix of the drill bit will soften. While diamond is the hardest substance known, at 10 on the Mohs hardness scale, it must remain firmly in the matrix to achieve cutting. Weight on bit, the force exerted on the cutting face of the bit by the drill rods in the hole above the bit, must also be monitored.

A unique drilling operation in deep ocean water was named Project Mohole.

New oilfield technologies

Research includes technologies based on the utilization of water jet, chemical plasma, hydrothermal spallation or laser.

Causes of deviation

Most drill holes deviate slightly from their planned trajectory. This is because of the torque of the turning bit working against the cutting face, because of the flexibility of the steel rods and especially the screw joints, because of reaction to foliation and structure within the rock, and because of refraction as the bit moves into different rock layers of varying resistance. Additionally, inclined holes will tend to deviate upwards because the drill rods will lie against the bottom of the bore, causing the drill bit to be slightly inclined from true. It is because of deviation that drill holes must be surveyed if deviation will impact the usefulness of the information returned. Sometimes the surface location can be offset laterally to take advantage of the expected deviation tendency, so the bottom of the hole will end up near the desired location. Oil well drilling commonly uses a process of controlled deviation called directional drilling (e.g., when several wells are drilled from one surface location).

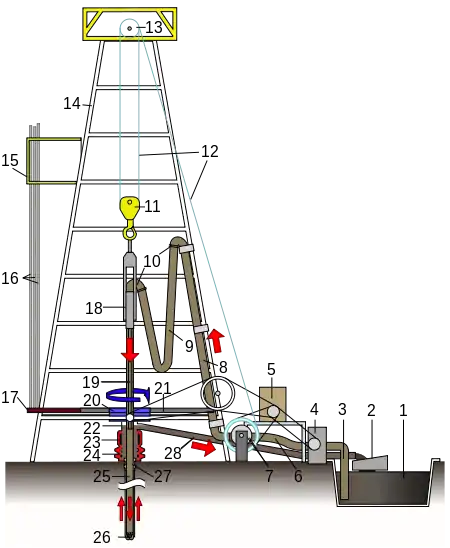

Rig equipment

Drilling rigs typically include at least some of the following items: See Drilling rig (petroleum) for a more detailed description.

- Blowout preventers: (BOPs)

The equipment associated with a rig is to some extent dependent on the type of rig but (#23 & #24) are devices installed at the wellhead to prevent fluids and gases from unintentionally escaping from the borehole. #23 is the annular (often referred to as the "Hydril", which is one manufacturer) and #24 is the pipe rams and blind rams. In the place of #24 Variable bore rams or VBRs can be used. These offer the same pressure and sealing capacity found in standard pipe rams, while offering the versatility of sealing on various sizes of drill pipe, production tubing and casing without changing standard pipe rams. Normally VBRs are used when utilizing a tapered drill string (when different size drill pipe is used in the complete drill string).

- Centrifuge: an industrial version of the device that separates fine silt and sand from the drilling fluid.

- Solids control: solids control equipment is for preparing drilling mud for the drilling rig.

- Chain tongs: wrench with a section of chain, that wraps around whatever is being tightened or loosened. Similar to a pipe wrench.

- Degasser: a device that separates air and/or gas from the drilling fluid.

- Desander / desilter: contains a set of hydrocyclones that separate sand and silt from the drilling fluid.

- Drawworks: (#7) is the mechanical section that contains the spool, whose main function is to reel in/out the drill line to raise/lower the traveling block (#11).

- Drill bit: (#26) is a device attached to the end of the drill string that breaks apart the rock being drilled. It contains jets through which the drilling fluid exits.

- Drill pipe: (#16) joints of hollow tubing used to connect the surface equipment to the bottom hole assembly (BHA) and acts as a conduit for the drilling fluid. In the diagram, these are "stands" of drill pipe which are 2 or 3 joints of drill pipe connected together and "stood" in the derrick vertically, usually to save time while tripping pipe.

- Elevators: a gripping device that is used to latch to the drill pipe or casing to facilitate the lowering or lifting (of pipe or casing) into or out of the borehole.

- Mud motor: a hydraulically powered device positioned just above the drill bit used to spin the bit independently from the rest of the drill string.

- Mud pump: (#4) reciprocal type of pump used to circulate drilling fluid through the system.

- Mud tanks: (#1) often called mud pits, provides a reserve store of drilling fluid until it is required down the wellbore.

- Rotary table: (#20) rotates the drill string along with the attached tools and bit.

- Shale shaker: (#2) separates drill cuttings from the drilling fluid before it is pumped back down the borehole.

Occupational safety

Drilling rigs create some safety challenges for those who work on them. One safety concern is the use of seatbelts for workers driving between two locations. Motor vehicle fatalities on the job for these workers is 8.5 times the rate of the rest of the US working population, which can be attributed to the low rate of seatbelt use.[8]

See also

References

- Smil, Vaclav (2017). Oil - A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1786072863.

- Heshelow, Kathy (2010). Investing in Oil and Gas: The ABC's of DPPs. Iuniverse. p. 52. ISBN 978-1450261715.

- Baars, D.L.; Watney, W.L.; Steeples, D.W.; Brostuen, E.A (1989). Petroleum; a primer for Kansas (Educational Series, no. 7 ed.). Kansas Geological Survey. p. 40. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

After the cementing of the casing has been completed, the drilling rig, equipment, and materials are removed from the drill site. A smaller rig, known as a workover rig or completion rig, is moved over the well bore. The smaller rig is used for the remaining completion operations.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Redwood, Boverton (1911). "Petroleum". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 316–323.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Redwood, Boverton (1911). "Petroleum". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 316–323. - Roughnecks, Rock Bits And Rigs: The Evolution Of Oil Well Drilling Technology In Alberta, 1883-1970 By Sandy Gow, Bonar Alexander Gow Published by University of Calgary Press, 2005 ISBN 1-55238-067-X

- "Ensign Launches Newest And Most Powerful Automated ADR 1500S Pad Drill Rigs In Montney Play", New Tech Magazine, Calgary, Alberta, 21 November 2014, archived from the original on 10 December 2014, retrieved 6 December 2014

- "Deer Creek And Ensign Spud First SAGD Wells Using Slant Automated Drilling Rig". newtechmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-10.

- Krah, Jaclyn; Unger, Richard L. (7 August 2013). "The Importance of Occupational Safety and Health: Making for a "Super" Workplace". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 16 January 2015.