Edgar Ray Killen

Edgar Ray Killen (January 17, 1925 – January 11, 2018) was a Ku Klux Klan organizer who planned and directed the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three civil rights activists participating in the Freedom Summer of 1964.[1][2] He was found guilty in state court of three counts of manslaughter on June 21, 2005, the forty-first anniversary of the crime, and sentenced to 60 years in prison. He appealed the verdict, but the sentence was upheld on April 12, 2007, by the Supreme Court of Mississippi.[3] He died in prison on January 11, 2018, six days before his 93rd birthday.[4][5]

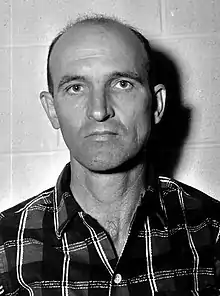

Edgar Ray Killen | |

|---|---|

Booking photo, late 1964 | |

| Born | January 17, 1925 Philadelphia, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | January 11, 2018 (aged 92) Parchman, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Other names | Preacher |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Conviction(s) | Manslaughter (3 counts) |

| Criminal charge | Murder (3 counts) |

| Penalty | 60 years imprisonment |

Early life

Edgar Ray Killen was born in Philadelphia, Mississippi, as the oldest of eight children[6] to Lonie Ray Killen (1901–1992) and Jetta Killen (née Hitt; 1903–1983). Killen was a sawmill operator and a part-time minister.[7] He was a kleagle, or klavern recruiter and organizer, for the Neshoba and Lauderdale County chapters of the Ku Klux Klan.[8]

Murders

During the "Freedom Summer" of 1964, James Chaney, 21, a young black man from Meridian, Mississippi and Andrew Goodman, 20, and Michael Schwerner, 24, two Jewish men from New York, were murdered in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Killen, along with Cecil Price, then deputy sheriff of Neshoba County, was found to have assembled a group of armed men who conspired against, pursued, and killed the three civil rights workers. Samuel Bowers, who served as the Grand Wizard of the local White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and had ordered the murders to take place,[9] acknowledged that Killen was "the main instigator".[9]

At the time of the murders, the state of Mississippi made little effort to prosecute the guilty parties. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), under pro-civil-rights President Lyndon B. Johnson and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, conducted a vigorous investigation. A federal prosecutor, John Doar, circumventing dismissals by federal judges, convened a grand jury in December 1964. In November 1965 Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall appeared before the Supreme Court to defend the federal government's authority in bringing charges. Eighteen men, including Killen, were arrested and charged with conspiracy to violate the victims' civil rights[10] in United States v. Price.

The trial, which began in 1966 at the federal courthouse of Meridian before an all-white jury,[11] convicted seven conspirators, including the deputy sheriff, and acquitted eight others. It was the first time a white jury convicted a white official of civil rights killings.[12] For three men, including Killen, the trial ended in a hung jury, with the jurors deadlocked 11–1 in favor of conviction. The lone holdout said that she could not convict a preacher. The prosecution decided not to retry Killen and he was released. None of the men found guilty would serve more than six years in prison.[13]

More than 20 years later, Jerry Mitchell, an award-winning investigative reporter for The Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi, wrote extensively about the case for six years. Mitchell helped to secure convictions in other high-profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the assassination of Medgar Evers, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, and the murder of Vernon Dahmer. Mitchell assembled new evidence regarding the murders of the three civil rights workers. He also located new witnesses and pressured the state to take action. Assisting Mitchell were high school teacher Barry Bradford and a team of three students from Illinois.[14]

The students persuaded Killen to do his only taped interview (to that point) about the murders. That tape showed Killen clinging to his segregationist views and competent and aware. The student-teacher team found more potential witnesses, created a website, lobbied the United States Congress, and focused national media attention on reopening the case. Carolyn Goodman, the mother of one of the victims, called them "super heroes".[14]

The film Mississippi Burning is related to the murders.

Reopening of the case

In early January 2004, a multiracial group of citizens in Neshoba County formed the Philadelphia Coalition, to seek justice in the 1964 murders. Led by co-chairs Leroy Clemons and Jim Prince, the group met over several months and then issued a call for justice, first in March 2004 and then on the 40th anniversary of the murders. At that event, attended by over 1500 people, including the sitting Mississippi governor and four congressmen, including Rep. John Lewis and Rep. Bennie Thompson, included a lauded speech by former Mississippi Secretary of State Dick Molpus, imploring those with information about the crimes to come forward.[15] After that June call for justice, the members of the Coalition met over the summer with the state attorney general Jim Hood, along with Andrew Goodman's mother Carolyn Goodman and brother David Goodman. They asked Hood to re-open the case. The group also met with local district attorney Mark Duncan. Throughout the process, the group was supported by the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation. In the fall of 2004, an anonymous donor provided funds through the Mississippi Religious Leadership Council for anyone with information leading to an arrest.

On January 6, 2005, after these numerous calls from local leaders, AG Hood and DA Duncan convened a local grand jury, which indicted Edgar Ray Killen for the murders.[16]

In 2004, Killen declared that he would attend a petition-drive on his behalf, which was to be conducted by the Nationalist Movement at the 2004 Mississippi Annual State Fair in Jackson. The Nationalist Movement is a white supremacy organization. The Hinds County sheriff, Malcolm McMillin, conducted a counter-petition, calling for a reopening of the state case against Killen. Killen was arrested for three counts of murder on January 6, 2005. He was freed on bond. His case drew comparisons to that of Byron De La Beckwith, who was charged with the killing of Medgar Evers in 1963 and rearrested in 1994.

Killen's trial was scheduled for April 18, 2005. It was deferred after the 80-year-old Killen broke both of his legs while chopping lumber at his rural home in Neshoba County. The trial began on June 13, 2005, with Killen attending in a wheelchair. He was found guilty of manslaughter on June 21, 2005, 41 years to the day after the crime. The jury, consisting of nine white jurors and three black jurors, rejected the charges of murder, but found him guilty of recruiting the mob that carried out the killings. He was sentenced on June 23, 2005, by Circuit Judge Marcus Gordon to the maximum sentence of 60 years in prison, 20 years for each count of manslaughter, to be served consecutively.[6] He would have been eligible for parole after serving at least 20 years. At the sentencing, Gordon stated that each life lost was valuable, and he said that the law made no distinction of age for the crime and that the maximum sentence should be imposed regardless of Killen's age. Prosecuting the case were Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood and Neshoba County District Attorney Mark Duncan.

On August 12, Killen was released from prison on a $600,000 appeal bond. He claimed that he could no longer use his right hand (using his left hand to place his right one on the Bible during his swearing-in) and that he was permanently confined to his wheelchair. Gordon said he was convinced by the testimony that Killen was neither a flight risk nor a danger to the community. On September 3, The Clarion-Ledger reported that a deputy sheriff saw Killen walking around "with no problem". At a hearing on September 9, several other deputies testified to seeing Killen driving in various locations. One deputy said that Killen shook hands with him using his right hand. Gordon revoked the bond and ordered Killen back to prison, saying that he believed Killen had committed a fraud against the court.[17]

On March 29, 2006, Killen was moved from his prison cell to a City of Jackson hospital to treat complications from the severe leg injury that he sustained in the 2005 logging incident. On August 12, 2007, the Supreme Court of Mississippi affirmed Killen's conviction by a vote of 8–0 (one judge not participating).[18]

Incarceration and death

Killen entered the Mississippi Department of Corrections system on June 27, 2005, to serve his sixty-year sentence (three twenty-year sentences running consecutively). That same year, after a circuit court judge denied Killen's request for a new trial, he was sent to the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility (CMCF) in an unincorporated area of Rankin County, near Pearl. He underwent evaluation, and prison officials were deciding whether to keep him at CMCF or to send him to the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman, an unincorporated community in Sunflower County.[19] Killen's release date was September 1, 2027 (by which time he would have been 102 years old). His location last changed on July 29, 2014.[20]

On February 25, 2010, the Associated Press reported that Killen filed a lawsuit against the FBI.[21] The suit alleged that one of Killen's lawyers in his 1967 trial, Clayton Lewis, was an FBI informant, and that the FBI hired "gangster and killer" Gregory Scarpa to coerce witnesses.[21] On February 18, 2011 U.S. Magistrate F. Keith Ball recommended that the lawsuit be dismissed. On March 23, 2011, District Judge Daniel P. Jordan, III, adopted the magistrate's report and dismissed the case.

James Hart Stern, a black preacher from California, shared a prison cell with Edgar Ray Killen from August 2010 to November 2011 while the former was serving time for wire fraud. During that time, Killen and Stern forged a close relationship and Killen hand wrote dozens of letters to Stern outlining his views on race as well as confessing to other crimes. In addition to the letters, the former leader of the KKK signed over power of attorney and his land in Mississippi to his cellmate.[22] Stern detailed his experience in the 2017 book Killen the KKK, co-authored by North Carolina author Autumn K. Robinson. Using his power of attorney, Stern disbanded Killen's incarnation of the KKK on January 5, 2016.[23]

On January 12, 2018, it was announced that he had died at the age of 92 at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi.[6][24]

See also

- Civil Rights Movement

- Neshoba (film)

References

- "'Mississippi Burning' Case Begins New Chapter, as Prof. Ken Bode Previews Trial - DePauw University". Depauw.edu. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- "Civil Rights Movement Archive Website – Neshoba Murders Case — A Chronology". Crmvet.org. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- Killen v. State, 958 So.2d 172 (Miss. 2007).

- Jerry Mitchell, The (Jackson, Miss.) Clarion-Ledger (January 12, 2018). "Klansman who orchestrated Mississippi Burning killings dies in prison". USA Today. Retrieved January 12, 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "A Race Against the Clock: The Authorized Biography of Edgar Ray "Preacher" Killen". Amazon.com. March 28, 2018. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- Goldstein, Richard (January 13, 2018). "Edgar Ray Killen, Convicted in '64 Killings of Rights Workers, Dies at 92". The New York Times.

- Profile, Law2.umkc.edu; accessed April 5, 2015.

- Sims, Patsy (November 5, 2014). "No Twang of Conscience Whatever". Oxford American. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- Jerry Mitchell, The (Jackson, Miss.) Clarion-Ledger (February 4, 2014). "Congressional honor sought for Freedom Summer martyrs". USA Today. Retrieved February 11, 2014.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- The Civil Rights Act of 1968, passed in part due to this case, provided for life imprisonment or the death penalty for deprivations of civil rights resulting in bodily injury or death. Prior to that, the maximum penalty was ten years.

- Prior to the 1986 Supreme Court decision Batson v. Kentucky, prosecutors could use the peremptory challenge to arbitrarily exclude individuals from a jury based solely on their race. In addition, all-white juries had been standard in the South because blacks were disenfranchised from voting since 1890, and therefore could not serve on juries.

- Campbell Robertson, "Last Chapter for a Courthouse Where Mississippi Faced Its Past", New York Times, September 18, 2012, pp. 1, 16

- "Edgar Ray Killen, the KKK leader convicted in the 'Mississippi Burning' killings, dies in prison". Latimes.com. January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- Gilbert, Kathy L. (March 9, 2005). "Students, teacher 'carry burden' for slain civil rights workers". United Methodist Church. United Methodist News Service. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2004/jun/21/dick-molpus-raises-the-roof-in-neshoba-county/

- See Renee Romano's Racial Reckoning: Prosecuting America's Civil Rights Murders and http://edition.cnn.com/2005/US/01/07/cnna.guyot/index.html

- Mitchell, Jerry (September 10, 2005). "Killen ordered back to prison". The Clarion-Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- "Mississippi: Convictions Upheld". The New York Times. April 13, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- Myers, Debbie Burt. "Killen taken to Rankin County correctional facility", The Neshoba Democrat, June 27, 2005; retrieved September 1, 2010.

- "Inmate Details: EDGAR KILLEN". Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

Tentative Release: 08/22/2027

- Holbrook Mohr (February 25, 2010). "Ex-Klansman sues FBI, claims agency used mafia hit man and secret informants against him". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- Moye, David (June 27, 2012). "James Stern Invites Government To Investigate Klansman Edgar Ray Killen's Mississippi Property". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- "Has this man just disbanded the Ku Klux Klan?". Public Pressure. January 9, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- "Klan Leader Edgar Ray Killen Dies in Prison". Time. January 12, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.