Electromagnetic compatibility

Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) is the ability of electrical equipment and systems to function acceptably in their electromagnetic environment, by limiting the unintentional generation, propagation and reception of electromagnetic energy which may cause unwanted effects such as electromagnetic interference (EMI) or even physical damage in operational equipment.[1] The goal of EMC is the correct operation of different equipment in a common electromagnetic environment. It is also the name given to the associated branch of electrical engineering.

EMC pursues three main classes of issue. Emission is the generation of electromagnetic energy, whether deliberate or accidental, by some source and its release into the environment. EMC studies the unwanted emissions and the countermeasures which may be taken in order to reduce unwanted emissions. The second class, susceptibility, is the tendency of electrical equipment, referred to as the victim, to malfunction or break down in the presence of unwanted emissions, which are known as Radio frequency interference (RFI). Immunity is the opposite of susceptibility, being the ability of equipment to function correctly in the presence of RFI, with the discipline of "hardening" equipment being known equally as susceptibility or immunity. A third class studied is coupling, which is the mechanism by which emitted interference reaches the victim.

Interference mitigation and hence electromagnetic compatibility may be achieved by addressing any or all of these issues, i.e., quieting the sources of interference, inhibiting coupling paths and/or hardening the potential victims. In practice, many of the engineering techniques used, such as grounding and shielding, apply to all three issues.

Introduction

While electromagnetic interference (EMI) is a phenomenon - the radiation emitted and its effects - electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) is an equipment characteristic or property - not to behave unacceptably in the EMI environment.

EMC ensures the correct operation, in the same electromagnetic environment, of different equipment items which use or respond to electromagnetic phenomena, and the avoidance of any interference effects. Another way of saying this is that EMC is the control of EMI so that unwanted effects are prevented.

Besides understanding the phenomena in themselves, EMC also addresses the countermeasures, such as control regimes, design and measurement, which should be taken in order to prevent emissions from causing any adverse effect.

Types of interference

Electromagnetic interference divides into several categories according to the source and signal characteristics.

The origin of interference, often called "noise" in this context, can be man-made (artificial) or natural.

Continuous interference

Continuous, or continuous wave (CW), interference arises where the source continuously emits at a given range of frequencies. This type is naturally divided into sub-categories according to frequency range, and as a whole is sometimes referred to as "DC to daylight".

- Audio frequency, from very low frequencies up to around 20 kHz. Frequencies up to 100 kHz may sometimes be classified as audio. Sources include:

- Mains hum from: power supply units, nearby power supply wiring, transmission lines and substations.

- Audio processing equipment, such as audio power amplifiers and loudspeakers.

- Demodulation of a high-frequency carrier wave such as an FM radio transmission.

- Radio frequency interference (RFI), from typically 20 kHz to an upper limit which constantly increases as technology pushes it higher. Sources include:

- Wireless and radio frequency transmissions

- Television and radio receivers

- Industrial, scientific and medical equipment (ISM)

- Digital processing circuitry such as microcontrollers

- Broadband noise may be spread across parts of either or both frequency ranges, with no particular frequency accentuated. Sources include:

- Solar activity

- Continuously operating spark gaps such as arc welders

- CDMA (spread-spectrum) mobile telephony

Pulse or transient interference

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP), sometimes called a transient disturbance, arises where the source emits a short-duration pulse of energy. The energy is usually broadband by nature, although it often excites a relatively narrow-band damped sine wave response in the victim.

Sources divide broadly into isolated and repetitive events.

- Sources of isolated EMP events include:

- Switching action of electrical circuitry, including inductive loads such as relays, solenoids, or electric motors.

- Power line surges/pulses

- Electrostatic discharge (ESD), as a result of two charged objects coming into close proximity or contact.

- Lightning electromagnetic pulse (LEMP), although typically a short series of pulses.

- Nuclear electromagnetic pulse (NEMP), as a result of a nuclear explosion. A variant of this is the high altitude EMP (HEMP) nuclear weapon, designed to create the pulse as its primary destructive effect.

- Non-nuclear electromagnetic pulse (NNEMP) weapons.

- Sources of repetitive EMP events, sometimes as regular pulse trains, include:

- Electric motors

- Electrical ignition systems, such as in gasoline engines.

- Continual switching actions of digital electronic circuitry.

Coupling mechanisms

Some of the technical words which are employed can be used with differing meanings. These terms are used here in a widely accepted way, which is consistent with other articles in the encyclopedia.

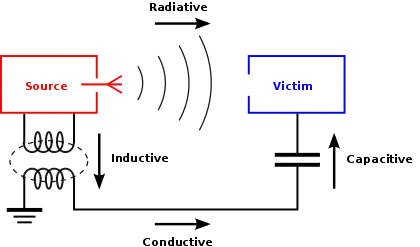

The basic arrangement of noise source, coupling path and victim, receptor or sink is shown in the figure below. Source and victim are usually electronic hardware devices, though the source may be a natural phenomenon such as a lightning strike, electrostatic discharge (ESD) or, in one famous case, the Big Bang at the origin of the Universe.

There are four basic coupling mechanisms: conductive, capacitive, magnetic or inductive, and radiative. Any coupling path can be broken down into one or more of these coupling mechanisms working together. For example the lower path in the diagram involves inductive, conductive and capacitive modes.

Conductive coupling

Conductive coupling occurs when the coupling path between the source and the receptor is formed by direct electrical contact with a conducting body, for example a transmission line, wire, cable, PCB trace or metal enclosure.

Conducted noise is also characterised by the way it appears on different conductors:

- Common-mode coupling: noise appears in phase (in the same direction) on two conductors.

- Differential-mode coupling: noise appears out of phase (in opposite directions) on two conductors.

Inductive coupling

Inductive coupling occurs where the source and receiver are separated by a short distance (typically less than a wavelength). Strictly, "Inductive coupling" can be of two kinds, electrical induction and magnetic induction. It is common to refer to electrical induction as capacitive coupling, and to magnetic induction as inductive coupling.

Capacitive coupling

Capacitive coupling occurs when a varying electrical field exists between two adjacent conductors typically less than a wavelength apart, inducing a change in voltage on the receiving conductor.

Magnetic coupling

Inductive coupling or magnetic coupling occurs when a varying magnetic field exists between two parallel conductors typically less than a wavelength apart, inducing a change in voltage along the receiving conductor.

Radiative coupling

Radiative coupling or electromagnetic coupling occurs when source and victim are separated by a large distance, typically more than a wavelength. Source and victim act as radio antennas: the source emits or radiates an electromagnetic wave which propagates across the space in between and is picked up or received by the victim.

EMC control

The damaging effects of electromagnetic interference pose unacceptable risks in many areas of technology, and it is necessary to control such interference and reduce the risks to acceptable levels.

The control of electromagnetic interference (EMI) and assurance of EMC comprises a series of related disciplines:

- Characterising the threat.

- Setting standards for emission and susceptibility levels.

- Design for standards compliance.

- Testing for standards compliance.

For a complex or novel piece of equipment, this may require the production of a dedicated EMC control plan summarizing the application of the above and specifying additional documents required.

Characterising the threat

Characterisation of the problem requires understanding of:

- The interference source and signal.

- The coupling path to the victim.

- The nature of the victim both electrically and in terms of the significance of malfunction.

The risk posed by the threat is usually statistical in nature, so much of the work in threat characterisation and standards setting is based on reducing the probability of disruptive EMI to an acceptable level, rather than its assured elimination.

Regulatory and standards bodies

Several organizations, both national and international, work to promote international co-operation on standardization (harmonization), including publishing various EMC standards. Where possible, a standard developed by one organization may be adopted with little or no change by others. This helps for example to harmonize national standards across Europe.

International standards organizations include:

- International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), which has several committees working full-time on EMC issues. These are:

- Technical Committee 77 (TC77), working on electromagnetic compatibility between equipment including networks.

- Comité International Spécial des Perturbations Radioélectriques (CISPR), or International Special Committee on Radio Interference.

- The Advisory Committee on Electromagnetic Compatibility (ACEC) co-ordinates the IEC's work on EMC between these committees.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO), which publishes standards for the automotive industry.

Among the main national organizations are:

- Europe:

- Comité Européen de Normalisation (CEN) or European Committee for Standardization).

- Comité Européen de Normalisation Electrotechniques (CENELEC) or European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardisation.

- European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI).

- United States:

- The Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

- The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE).

- The Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics (RTCA); see DO-160

- Britain: The British Standards Institution (BSI).

- Germany: The Verband der Elektrotechnik, Elektronik und Informationstechnik (VDE) or Association for Electrical, Electronic and Information Technologies.

Laws

Compliance with national or international standards is usually laid down by laws passed by individual nations. Different nations can require compliance with different standards.

In European law, manufacturers of electronic devices are advised to run EMC tests in order to comply with compulsory CE-labeling. EU directive 2004/108/EC (previously 89/336/EEC) on EMC defines the rules for the distribution of electric devices within the European Union. More are given in the list of EMC directives.

In 2019, the USA adopted a program for the protection of critical infrastructure against an electromagnetic pulse, whether caused by a geomagnetic storm or a high-altitude nuclear weapon.[2]

EMC design

Electromagnetic noise is produced in the source due to rapid current and voltage changes, and spread via the coupling mechanisms described earlier.

Breaking a coupling path is equally effective at either the start or the end of the path, therefore many aspects of good EMC design practice apply equally to potential emitters and to potential victims.

A design which easily couples energy to the outside world will equally easily couple energy in and will be susceptible. A single improvement will often reduce both emissions and susceptibility.

Grounding and shielding

Grounding and shielding aim to reduce emissions or divert EMI away from the victim by providing an alternative, low-impedance path. Techniques include:

- Grounding or earthing schemes such as star earthing for audio equipment or ground planes for RF. The scheme must also satisfy safety regulations.

- Shielded cables, where the signal wires are surrounded by an outer conductive layer that is grounded at one or both ends.

- Shielded housings. A conductive metal housing will act as an interference shield. In order to access the interior, such a housing is typically made in sections (such as a box and lid); an RF gasket may be used at the joints to reduce the amount of interference that leaks through. RF gaskets come in various types. A plain metal gasket may be either braided wire or a flat strip slotted to create many springy "fingers". Where a waterproof seal is required, a flexible elastomeric base may be impregnated with chopped metal fibers dispersed into the interior or long metal fibers covering the surface or both.

Other general measures

- Decoupling or filtering at critical points such as cable entries and high-speed switches, using RF chokes and/or RC elements. A line filter implements these measures between a device and a line.

- Transmission line techniques for cables and wiring, such as balanced differential signal and return paths, and impedance matching.

- Avoidance of antenna structures such as loops of circulating current, resonant mechanical structures, unbalanced cable impedances or poorly grounded shielding.

- Eliminating spurious rectifying junctions that can form between metal structures around and near transmitter installations. Such junctions in combination with unintentional antenna structures can radiate harmonics of the transmitter frequency.

Emissions suppression

Additional measures to reduce emissions include:

- Avoid unnecessary switching operations. Necessary switching should be done as slowly as is technically possible.

- Noisy circuits (with a lot of switching activity) should be physically separated from the rest of the design.

- High peaks can be avoided by using the spread spectrum method, in which different parts of the circuit emit at different frequencies.

- Harmonic wave filters.

- Design for operation at lower signal levels, reducing the energy available for emission.

Susceptibility hardening

Additional measures to reduce susceptibility include:

- Fuses, trip switches and circuit breakers.

- Transient absorbers.

- Design for operation at higher signal levels, reducing the relative noise level in comparison.

- Error-correction techniques in digital circuitry. These may be implemented in hardware, software or a combination of both.

- Differential signaling or other common-mode noise techniques for signal routing

EMC testing

Testing is required to confirm that a particular device meets the required standards. It divides broadly into emissions testing and susceptibility testing.

Open-area test sites, or OATS, are the reference sites in most standards. They are especially useful for emissions testing of large equipment systems.

However RF testing of a physical prototype is most often carried out indoors, in a specialised EMC test chamber. Types of chamber include anechoic, reverberation and the gigahertz transverse electromagnetic cell (GTEM cell).

Sometimes computational electromagnetics simulations are used to test virtual models.

Like all compliance testing, it is important that the test equipment, including the test chamber or site and any software used, be properly calibrated and maintained.

Typically, a given run of tests for a particular piece of equipment will require an EMC test plan and follow-up test report. The full test program may require the production of several such documents.

Emissions testing

Emissions are typically measured for radiated field strength and where appropriate for conducted emissions along cables and wiring. Inductive (magnetic) and capacitive (electric) field strengths are near-field effects, and are only important if the device under test (DUT) is designed for location close to other electrical equipment.

For conducted emissions, typical transducers include the LISN (line impedance stabilisation network) or AMN (artificial mains network) and the RF current clamp.

For radiated emission measurement, antennas are used as transducers. Typical antennas specified include dipole, biconical, log-periodic, double ridged guide and conical log-spiral designs. Radiated emissions must be measured in all directions around the DUT.

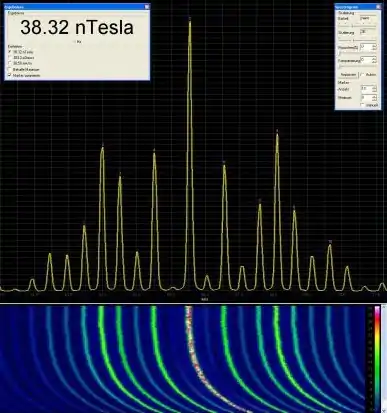

Specialized EMI test receivers or EMI analysers are used for EMC compliance testing. These incorporate bandwidths and detectors as specified by international EMC standards. An EMI receiver may be based on a spectrum analyser to measure the emission levels of the DUT across a wide band of frequencies (frequency domain), or on a tunable narrower-band device which is swept through the desired frequency range. EMI receivers along with specified transducers can often be used for both conducted and radiated emissions. Pre-selector filters may also be used to reduce the effect of strong out-of-band signals on the front-end of the receiver.

Some pulse emissions are more usefully characterized using an oscilloscope to capture the pulse waveform in the time domain.

Susceptibility testing

Radiated field susceptibility testing typically involves a high-powered source of RF or EM energy and a radiating antenna to direct the energy at the potential victim or device under test (DUT).

Conducted voltage and current susceptibility testing typically involves a high-powered signal generator, and a current clamp or other type of transformer to inject the test signal.

Transient or EMP signals are used to test the immunity of the DUT against powerline disturbances including surges, lightning strikes and switching noise.[3] In motor vehicles, similar tests are performed on battery and signal lines.[4][5] The transient pulse may be generated digitally and passed through a broadband pulse amplifier, or applied directly to the transducer from a specialised pulse generator.

Electrostatic discharge testing is typically performed with a piezo spark generator called an "ESD pistol". Higher energy pulses, such as lightning or nuclear EMP simulations, can require a large current clamp or a large antenna which completely surrounds the DUT. Some antennas are so large that they are located outdoors, and care must be taken not to cause an EMP hazard to the surrounding environment.

History

Origins

The earliest EMC issue was lightning strike (lightning electromagnetic pulse, or LEMP) on ships and buildings. Lightning rods or lightning conductors began to appear in the mid-18th century. With the advent of widespread electricity generation and power supply lines from the late 19th century on, problems also arose with equipment short-circuit failure affecting the power supply, and with local fire and shock hazard when the power line was struck by lightning. Power stations were provided with output circuit breakers. Buildings and appliances would soon be provided with input fuses, and later in the 20th century miniature circuit breakers (MCB) would come into use.

Early twentieth century

It may be said that radio interference and its correction arose with the first spark-gap experiment of Marconi in the late 1800s.[6] As radio communications developed in the first half of the 20th century, interference between broadcast radio signals began to occur and an international regulatory framework was set up to ensure interference-free communications.

Switching devices became commonplace through the middle of the 20th century, typically in petrol powered cars and motorcycles but also in domestic appliances such as thermostats and refrigerators. This caused transient interference with domestic radio and (after World War II) TV reception, and in due course laws were passed requiring the suppression of such interference sources.

ESD problems first arose with accidental electric spark discharges in hazardous environments such as coal mines and when refuelling aircraft or motor cars. Safe working practices had to be developed.

Postwar period

After World War II the military became increasingly concerned with the effects of nuclear electromagnetic pulse (NEMP), lightning strike, and even high-powered radar beams, on vehicle and mobile equipment of all kinds, and especially aircraft electrical systems.

When high RF emission levels from other sources became a potential problem (such as with the advent of microwave ovens), certain frequency bands were designated for Industrial, Scientific and Medical (ISM) use, allowing emission levels limited only by thermal safety standards. A variety of issues such as sideband and harmonic emissions, broadband sources, and the ever-increasing popularity of electrical switching devices and their victims, resulted in a steady development of standards and laws.

From the late 1970s, the popularity of modern digital circuitry rapidly grew. As the technology developed, with ever-faster switching speeds (increasing emissions) and lower circuit voltages (increasing susceptibility), EMC increasingly became a source of concern. Many more nations became aware of EMC as a growing problem and issued directives to the manufacturers of digital electronic equipment, which set out the essential manufacturer requirements before their equipment could be marketed or sold. Organizations in individual nations, across Europe and worldwide, were set up to maintain these directives and associated standards. In 1979 the American FCC published a regulation that required the electromagnetic emissions of all "digital devices" to be below certain limits.[6] This regulatory environment led to a sharp growth in the EMC industry supplying specialist devices and equipment, analysis and design software, and testing and certification services. Low-voltage digital circuits, especially CMOS transistors, became more susceptible to ESD damage as they were miniaturised and, despite the development of on-chip hardening techniques, a new ESD regulatory regime had to be developed.

Modern era

From the 1980s on the explosive growth in mobile communications and broadcast media channels put huge pressure on the available airspace. Regulatory authorities began squeezing band allocations closer and closer together, relying on increasingly sophisticated EMC control methods, especially in the digital communications domain, to keep cross-channel interference to acceptable levels. Digital systems are inherently less susceptible than analogue systems, and also offer far easier ways (such as software) to implement highly sophisticated protection and error-correction measures.

In 1985 the USA released the ISM bands for low-power mobile digital communications, leading to the development of Wi-Fi and remotely-operated car door keys. This approach relies on the intermittent nature of ISM interference and use of sophisticated error-correction methods to ensure lossless reception during the quiet gaps between any bursts of interference.

See also

- Conducted electromagnetic interference

- Crosstalk

- EMC-aware programming

- IEEE Electromagnetic Compatibility Society

- International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP)

- List of common EMC test standards

- Television interference

References

- DIN EN 61000-2-2 VDE 0839-2-2:2003-02 - Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC). VDE. 2003.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document: "Executive Order on Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Government document: "Executive Order on Coordinating National Resilience to Electromagnetic Pulses". - EMC Testing and Standards in Transient Immunity Testing, RF Immunity. Electronics-project-design.com. Retrieved on 2011-07-19.

- ISO 7637-2:2004/Amd 1:2008. Iso.org (2011-03-01). Retrieved on 2011-07-19.

- ISO 7637-3:2007 – Road vehicles – Electrical disturbances from conduction and coupling – Part 3: Electrical transient transmission by capacitive and inductive coupling via lines other than supply lines. Iso.org (2010-09-06). Retrieved on 2011-07-19.

- Clayton, Paul (2008). Introduction to electromagnetic compatibility. Wiley. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-265-2875-2.

External links

| The Wikibook Practical Electronics has a page on the topic of: EMC design guidelines |

Web sites

- Automotive EMC Network

- EMC-Directive European Commission – Harmonised standards for EMC

- European EMI and EMC Conformity Assessment

- Federal Communications Commission

- News and information on Electromagnetic Compatibility regulations

- Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics

- Summary of EU standards by equipment type

General introductions

- What is EMC? YouTube video.

- Introduction to EMC

- Basics in EMC/EMI and Powerquality

Specific topics

- Analog, RF & EMC Considerations in Printed Wiring Board Design

- Application Note: Design for EMC Compliance

- Design for EMC - Effects of Via Slots, Split Planes,Gaps and Return Paths on Clock Signal

- EMC Design Fundamentals

- EMC Design Guidelines

- EMC engineering practices for panel builders

- EMC Resources (Clemson University)

- Fundamentals of the Plane Electromagnetic Shield