Eloesser flap

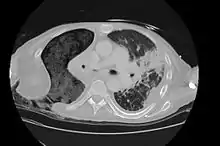

The Eloesser flap is a surgical procedure developed by Dr. Leo Eloesser in 1935 at the San Francisco General Hospital.[1] It was originally intended to aid with drainage of tuberculous empyemas, since at the time there were no effective medications to treat tuberculosis. The procedure was used extensively[2] until the development of effective chemotherapy for tuberculosis in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[3] It is still used occasionally for chronic empyemas.[4][5]

Technique

As originally described by Dr. Eloesser, the procedure started with cutting a 2 inch wide, U-shaped flap of skin on the side of the chest wall underneath the axilla and scapula. The section of rib under the top of the flap was also removed. The finger-like skin flap was then inserted into the cavity made in the chest wall and sewn into the inner pleural lining of the chest. The edges of the incision are then brought together.[1] The flap allows for 1) passive drainage of the pleural space and 2) negative pressure to develop in the thoracic cavity due to it being easier for air to escape than to enter the chest. The lung can then expand to the chest wall and seal the inner opening of the flap.[3] Other surgeons have subsequently proposed modifications to the procedure.[6]

Modern use

The Eloesser flap is still utilized for patients with chronic empyemas who have not improved despite being treated with antibiotics and first line surgical procedures to remove pus and re-expand the lung such as decortication or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.[4] Often they are thought to be too ill for more definitive procedures such as a major thoracotomy or muscle flap transposition.[5] In a recent case series, the most common reasons to need an Eloesser flap were parapneumonic effusions and postresection empyemas, with only 9% done for tuberculosis.[4]

Complications

A downside to the procedure is that a permanent drainage path from the thoracic cavity is made and will need prolonged wound care and dressing changes.[4][5] Complications can also include sepsis.[4]

History

Prior to the development of the Eloesser flap in the 1930s, the main surgical treatments for chronic tuberculous empyema were an open thoracotomy or chest tube drainage. In his original published description of the procedure, Dr. Eloesser wrote that he felt that those options were "unsatisfactory" as he felt they led to secondary infection and death.[1] Another option included removing the infected fluid with a needle through the chest wall (percutaneous drainage) but it often quickly reaccumulated. Dr. Eloesser explained that when developing his procedure he wished to maintain drainage as with a chest tube to allow the lung to re-expand but without the presence of the chest tube that he felt "tends to keep up fever and sepsis."[1]

References

- ELOESSER, L. (1935-10-01). "An operation for tuberculous empyema". Chest. 1 (8): 8–23. doi:10.1378/chest.1.8.8. ISSN 0012-3692.

- Brown, A.Lincoln (1943). "Simple drainage of intrathoracic suppurations". The American Journal of Surgery. 62 (2): 169–184. doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(43)90247-8.

- Eloesser, Leo (1969). "Of an Operation for Tuberculous Empyema". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 8 (4): 355–357. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(10)66250-9.

- Thourani, Vinod H; Lancaster, R.Todd; Mansour, Kamal A; Miller, Joseph I (2003). "Twenty-six years of experience with the modified eloesser flap". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 76 (2): 401–406. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00470-3.

- Denlinger, Chadrick E. (2010). "Eloesser Flap Thoracostomy Window". Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 15 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1053/j.optechstcvs.2010.03.003.

- Symbas, Panagiotis N.; Nugent, Jeffrey T.; Abbott, Osier A.; Logan, William D.; Hatcher, Charles R. (1971). "Nontuberculous Pleural Empyema in Adults : The Role of a Modified Eloesser Procedure in Its Management". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 12 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65095-3. PMID 4933305.

External links

Media related to Eloesser flap at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eloesser flap at Wikimedia Commons