Energy conversion efficiency

Energy conversion efficiency (η) is the ratio between the useful output of an energy conversion machine and the input, in energy terms. The input, as well as the useful output may be chemical, electric power, mechanical work, light (radiation), or heat.

Overview

Energy conversion efficiency depends on the usefulness of the output. All or part of the heat produced from burning a fuel may become rejected waste heat if, for example, work is the desired output from a thermodynamic cycle. Energy converter is an example of an energy transformation. For example a light bulb falls into the categories energy converter. Even though the definition includes the notion of usefulness, efficiency is considered a technical or physical term. Goal or mission oriented terms include effectiveness and efficacy.

Generally, energy conversion efficiency is a dimensionless number between 0 and 1.0, or 0% to 100%. Efficiencies may not exceed 100%, e.g., for a perpetual motion machine. However, other effectiveness measures that can exceed 1.0 are used for heat pumps and other devices that move heat rather than convert it.

When talking about the efficiency of heat engines and power stations the convention should be stated, i.e., HHV (a.k.a. Gross Heating Value, etc.) or LCV (a.k.a. Net Heating value), and whether gross output (at the generator terminals) or net output (at the power station fence) are being considered. The two are separate but both must be stated. Failure to do so causes endless confusion.

Related, more specific terms include

- Electrical efficiency, useful power output per electrical power consumed;

- Mechanical efficiency, where one form of mechanical energy (e.g. potential energy of water) is converted to mechanical energy (work);

- Thermal efficiency or Fuel efficiency, useful heat and/or work output per input energy such as the fuel consumed;

- 'Total efficiency', e.g., for cogeneration, useful electric power and heat output per fuel energy consumed. Same as the thermal efficiency.

- Luminous efficiency, that portion of the emitted electromagnetic radiation is usable for human vision.

Fuel heating values and efficiency

In Europe the usable energy content of a fuel is typically calculated using the lower heating value (LHV) of that fuel, the definition of which assumes that the water vapor produced during fuel combustion (oxidation) remains gaseous, and is not condensed to liquid water so the latent heat of vaporization of that water is not usable. Using the LHV, a condensing boiler can achieve a "heating efficiency" in excess of 100% (this does not violate the first law of thermodynamics as long as the LHV convention is understood, but does cause confusion). This is because the apparatus recovers part of the heat of vaporization, which is not included in the definition of the lower heating value of a fuel. In the U.S. and elsewhere, the higher heating value (HHV) is used, which includes the latent heat for condensing the water vapor, and thus the thermodynamic maximum of 100% efficiency cannot be exceeded.

Wall-plug efficiency, luminous efficiency, and efficacy

In optical systems such as lighting and lasers, the energy conversion efficiency is often referred to as wall-plug efficiency. The wall-plug efficiency is the measure of output radiative-energy, in watts (joules per second), per total input electrical energy in watts. The output energy is usually measured in terms of absolute irradiance and the wall-plug efficiency is given as a percentage of the total input energy, with the inverse percentage representing the losses.

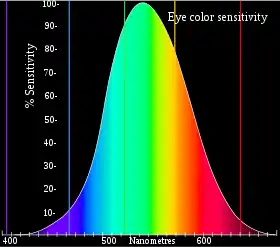

The wall-plug efficiency differs from the luminous efficiency in that wall-plug efficiency describes the direct output/input conversion of energy (the amount of work that can be performed) whereas luminous efficiency takes into account the human eye's varying sensitivity to different wavelengths (how well it can illuminate a space). Instead of using watts, the power of a light source to produce wavelengths proportional to human perception is measured in lumens. The human eye is most sensitive to wavelengths of 555 nanometers (greenish-yellow) but the sensitivity decreases dramatically to either side of this wavelength, following a Gaussian power-curve and dropping to zero sensitivity at the red and violet ends of the spectrum. Due to this the eye does not usually see all of the wavelengths emitted by a particular light-source, nor does it see all of the wavelengths within the visual spectrum equally. Yellow and green, for example, make up more than 50% of what the eye perceives as being white, even though in terms of radiant energy white-light is made from equal portions of all colors (i.e.: a 5 mw green laser appears brighter than a 5 mw red laser, yet the red laser stands-out better against a white background). Therefore, the radiant intensity of a light source may be much greater than its luminous intensity, meaning that the source emits more energy than the eye can use. Likewise, the lamp's wall-plug efficiency is usually greater than its luminous efficiency. The effectiveness of a light source to convert electrical energy into wavelengths of visible light, in proportion to the sensitivity of the human eye, is referred to as luminous efficacy, which is measured in units of lumens per watt (lm/w) of electrical input-energy.

Unlike efficacy (effectiveness), which is a unit of measurement, efficiency is a unitless number expressed as a percentage, requiring only that the input and output units be of the same type. The luminous efficiency of a light source is thus the percentage of luminous efficacy per theoretical maximum efficacy at a specific wavelength. The amount of energy carried by a photon of light is determined by its wavelength. In lumens, this energy is offset by the eye's sensitivity to the selected wavelengths. For example, a green laser pointer can have greater than 30 times the apparent brightness of a red pointer of the same power output. At 555 nm in wavelength, 1 watt of radiant energy is equivalent to 685 lumens, thus a monochromatic light source at this wavelength, with a luminous efficacy of 685 lm/w, has a luminous efficiency of 100%. The theoretical-maximum efficacy lowers for wavelengths at either side of 555 nm. For example, low-pressure sodium lamps produce monochromatic light at 589 nm with a luminous efficacy of 200 lm/w, which is the highest of any lamp. The theoretical-maximum efficacy at that wavelength is 525 lm/w, so the lamp has a luminous efficiency of 38.1%. Because the lamp is monochromatic, the luminous efficiency nearly matches the wall-plug efficiency of < 40%.[1][2]

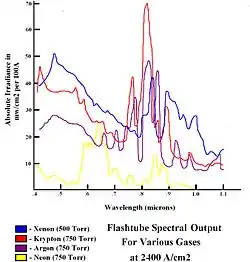

Calculations for luminous efficiency become more complex for lamps that produce white light or a mixture of spectral lines. Fluorescent lamps have higher wall-plug efficiencies than low-pressure sodium lamps, but only have half the luminous efficacy of ~ 100 lm/w, thus the luminous efficiency of fluorescents is lower than sodium lamps. A xenon flashtube has a typical wall-plug efficiency of 50–70%, exceeding that of most other forms of lighting. Because the flashtube emits large amounts of infrared and ultraviolet radiation, only a portion of the output energy is used by the eye. The luminous efficacy is therefore typically around 50 lm/w. However, not all applications for lighting involve the human eye nor are restricted to visible wavelengths. For laser pumping, the efficacy is not related to the human eye so it is not called "luminous" efficacy, but rather simply "efficacy" as it relates to the absorption lines of the laser medium. Krypton flashtubes are often chosen for pumping Nd:YAG lasers, even though their wall-plug efficiency is typically only ~ 40%. Krypton's spectral lines better match the absorption lines of the neodymium-doped crystal, thus the efficacy of krypton for this purpose is much higher than xenon; able to produce up to twice the laser output for the same electrical input.[3][4] All of these terms refer to the amount of energy and lumens as they exit the light source, disregarding any losses that might occur within the lighting fixture or subsequent output optics. Luminaire efficiency refers to the total lumen-output from the fixture per the lamp output.[5]

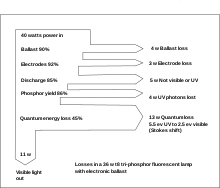

With the exception of a few light sources, such as incandescent light bulbs, most light sources have multiple stages of energy conversion between the "wall plug" (electrical input point, which may include batteries, direct wiring, or other sources) and the final light-output, with each stage producing a loss. Low-pressure sodium lamps initially convert the electrical energy using an electrical ballast, to maintain the proper current and voltage, but some energy is lost in the ballast. Similarly, fluorescent lamps also convert the electricity using a ballast (electronic efficiency). The electricity is then converted into light energy by the electrical arc (electrode efficiency and discharge efficiency). The light is then transferred to a fluorescent coating that only absorbs suitable wavelengths, with some losses of those wavelengths due to reflection off and transmission through the coating (transfer efficiency). The number of photons absorbed by the coating will not match the number then reemitted as fluorescence (quantum efficiency). Finally, due to the phenomenon of the Stokes shift, the re-emitted photons will have a longer wavelength (thus lower energy) than the absorbed photons (fluorescence efficiency). In very similar fashion, lasers also experience many stages of conversion between the wall plug and the output aperture. The terms "wall-plug efficiency" or "energy conversion efficiency" are therefore used to denote the overall efficiency of the energy-conversion device, deducting the losses from each stage, although this may exclude external components needed to operate some devices, such as coolant pumps.[6][7]

Example of energy conversion efficiency

| Conversion process | Conversion type | Energy efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity generation | ||

| Gas turbine | Thermal to electrical | up to 40% |

| Gas turbine plus steam turbine (combined cycle) | Thermal to electrical | up to 62.22%[8] |

| Water turbine | Gravitational to electrical | up to 90% (practically achieved) |

| Wind turbine | Kinetic to electrical | up to 59% (theoretical limit) |

| Solar cell | Radiative to electrical | 6–40% (technology-dependent, 15-20% most often, 85–90% theoretical limit) |

| Fuel cell | Chemical to electrical | up to 85% |

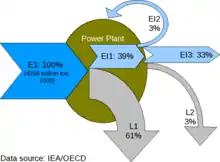

| World Electricity generation 2008 | Gross output 39% | Net output 33%[9] |

| Electricity storage | ||

| Lithium-ion battery | Chemical to electrical/reversible | 80–90% [10] |

| Nickel-metal hydride battery | Chemical to electrical/reversible | 66% [11] |

| Lead-acid battery | Chemical to electrical/reversible | 50–95% [12] |

| Engine/motor | ||

| Combustion engine | Chemical to kinetic | 10–50%[13] |

| Electric motor | Electrical to kinetic | 70–99.99% (> 200 W); 50–90% (10–200 W); 30–60% (< 10 W) |

| Turbofan | Chemical to kinetic | 20-40%[14] |

| Natural process | ||

| Photosynthesis | Radiative to chemical | 0.1% (average)[15] to 2% (best);[16] up to 6% in principle[17] (see main: Photosynthetic efficiency) |

| Muscle | Chemical to kinetic | 14–27% |

| Appliance | ||

| Household refrigerator | Electrical to thermal | low-end systems ~ 20%; high-end systems ~ 40–50% |

| Incandescent light bulb | Electrical to radiative | 0.7–5.1%,[18] 5–10% |

| Light-emitting diode (LED) | Electrical to radiative | 4.2–53%[19] |

| Fluorescent lamp | Electrical to radiative | 8.0–15.6%,[18] 28%[20] |

| Low-pressure sodium lamp | Electrical to radiative | 15.0–29.0%,[18] 40.5%[20] |

| Metal-halide lamp | Electrical to radiative | 9.5–17.0%,[18] 24%[20] |

| Switched-mode power supply | Electrical to electrical | currently up to 96% practically |

| Electric shower | Electrical to thermal | 90–95% (multiply by the energy efficiency of electricity generation to compare with other water-heating systems) |

| Electric heater | Electrical to thermal | ~100% (essentially all energy is converted into heat, multiply by the energy efficiency of electricity generation to compare with other heating systems) |

| Others | ||

| Firearm | Chemical to kinetic | ~30% (.300 Hawk ammunition) |

| Electrolysis of water | Electrical to chemical | 50–70% (80–94% theoretical maximum) |

See also

References

- Applied Atomic Collision Physics, Volume 5 by H. S. W. Massey, E. W. McDaniel, B. Bederson -- Academic Press 1982 Page 383

- https://www.photonics.com/a28677/Efficacy_Limits_for_Solid-State_White_Light

- Advanced Optical Instruments and Techniques by Daniel Malacara Hernández -- CRC Press 2018 Page 589

- Solid-state laser engineering by Walter Koechner – Springer-Verlag 1965 Page 335

- Understanding LED Illumination by M. Nisa Khan -- CRC Press 2014 Page 21--23

- https://www.rp-photonics.com/wall_plug_efficiency.html

- Handbook of Luminescent Semiconductor Materials by Leah Bergman, Jeanne L. McHale -- CRC Press 2012 Page 270

- Swatman, Rachel (2016-07-05). "General Electric and EDF build world's most efficient combined cycle power plant in France". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- IEC/OECD 2008 Energy Balance for World, accessdate 2011-06-08

- Valøen, Lars Ole and Shoesmith, Mark I. (2007). The effect of PHEV and HEV duty cycles on battery and battery pack performance (PDF). 2007 Plug-in Highway Electric Vehicle Conference: Proceedings. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- "NiMH Battery Charging Basics". PowerStream.com.

- PowerSonic, Technical Manual (PDF), p. 19, retrieved January 2014

- "Motivations for Promoting Clean Diesels" (PDF). US Department Of Energy. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2008.

- "11.5 Trends in thermal and propulsive efficiency". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 2016-10-26.

- Govindjee, What is photosynthesis?

- The Green Solar Collector; converting sunlight into algal biomass Wageningen University project (2005—2008)

- Miyamoto K. "Chapter 1 - Biological energy production". Renewable biological systems for alternative sustainable energy production (FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin - 128). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- Luminous efficacy#Lighting efficiency

- "All in 1 LED Lighting Solutions Guide". PhilipsLumileds.com. Philips. 2012-10-04. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-03-31. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- Light Pollution Handbook. Springer. 2004. ISBN 9781402026652.