Ernst Moritz Hess

Ernst Moritz Hess (20 March 1890 – 14 September 1983) was a baptized German Jew who served in the Imperial German Army during the First World War. He commanded the company of the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 in which Adolf Hitler served during the war. During the inter-war period he served as a judge before being forced out of office after the passing of the Nuremberg Laws by the Nazis in 1935, as he was classified as a "full-blooded Jew" due to his mother being Jewish, even though he was baptised a Protestant.

Ernst Moritz Hess | |

|---|---|

| Born | Ernst Moritz Hess 20 March 1890 |

| Died | 14 September 1983 (aged 93) Frankfurt am Main, Hesse, Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Soldier, judge, railway administrator |

| Spouse(s) | Margarete Witte |

| Children | 1 |

He emigrated with his family to Bolzano in Italy to escape Nazi persecution but was eventually forced to move back to Germany, though as a former war comrade of Hitler's he was granted protection and some privileges for a while. However, his privileges were removed in 1941 and he spent the rest of the war as a forced labourer; his sister died in Auschwitz but his mother managed to escape to Switzerland in 1945. Following the war he began a new career in railway management and was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany for his services to the Deutsche Bundesbahn.

Early life and war service

Born in Gelsenkirchen in what was then the Rhine Province of the Kingdom of Prussia, Hess lived in Düsseldorf before the First World War.[1] His father Julius was a lawyer and his mother Elisabeth was a member of a Jewish banking family from Wetzlar.[2][notes 1] Despite his Jewish ancestry on his mother's side, he was baptised and brought up as a Protestant Christian.

On the outbreak of war he enlisted as an officer in the 2nd Royal Bavarian Reserve Infantry and was posted to the front line in Flanders, where he suffered a serious wound in October 1914. Hitler served as a Gefreiter in the same regiment and in the summer of 1916, Hess briefly became Hitler's commanding officer. He sustained another serious wound the following October and was sent to Germany to recuperate. Hess was well regarded as a soldier and was decorated several times, receiving the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class as well as the Bavarian Military Order of Merit. In 1918 he was promoted to Lieutenant and in 1934 he was awarded the Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918.[2]

After the war Hess became a judge in Düsseldorf, where he lived with his wife Margarete and daughter Ursula. Hitler's rise to prominence came as a surprise to Hess and many of his colleagues from the regiment. The future dictator had been something of a non-entity during his time in the army, with no real friends within the regiment and little personal interaction with others. Hess regarded Hitler as "an absolute cypher" and spoke of his surprise that Hitler had been one of his comrades: "What, Hitler? He was in our unit? We never even noticed him."[2]

Discrimination and exile

Hitler's accession to power led to the passage of a series of antisemitic laws banning Jews from the civil service. Although Hess was a Protestant Christian, the laws defined him as a "full-blooded Jew" as he had four Jewish grandparents.[2] In April 1933, a "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service" was passed banning many Jews from public service. Hess survived this first purge of Jews owing to the "front-line fighters' privilege" (Frontkämpferprivileg) he was able to invoke as a consequence of his war service.[1] The Frontkämpferprivileg was instituted after Reichspräsident Paul von Hindenburg protested to Hitler that Jewish war veterans were being dismissed from state employment. Those who could prove that they had served on the front lines of the war were allowed to invoke the Frontkämpferprivileg to stay in their jobs.[3]

However, in the autumn of 1935 the Nuremberg Laws revoked this privilege and instituted a full ban on Jews in the civil service. Hess had to leave his job as a judge at the start of 1936 and was forced out of Düsseldorf after being beaten up by Nazi supporters outside his house in the autumn of that year. He moved with his family to Wuppertal, then in October 1937 emigrated to Bolzano in the German-speaking South Tyrol region of Italy, where he could continue the education in German of his 11-year-old daughter.[2]

Hess sought to lessen the impact of his racial classification by petitioning Hitler to make an exemption for himself and his daughter, who was classified as a "Mischling (crossbreed) 1st degree". In a letter sent in June 1936, Hess highlighted his Christian upbringing, patriotic outlook and military service. He wrote: "For us, it is a kind of spiritual death to now be branded as Jews and exposed to general contempt." He was aided by Fritz Wiedemann, who had been an aide de camp in his regiment's headquarters and later served as Hitler's personal adjutant between 1934–39. Wiedemann was able to intercede with Hans Heinrich Lammers, Head of the Reich Chancellery, who was also a war veteran.[2]

Although Hitler turned down Hess's petition, a number of concessions were nonetheless made; Hess was allowed to continue receiving his pension, although at a reduced rate, he was exempted from the obligation to adopt the middle name "Israel" identifying himself as a Jew, and he was able to acquire a new passport that was not stamped with a red "J", enabling him to travel abroad—a privilege that Jews no longer possessed by this time.[2]

Return to Germany

In October 1939, Hitler and Mussolini concluded the South Tyrol Option Agreement under which the German-speaking population of South Tyrol was given the choice of complete Italianisation—abandoning their German language and even their personal names—or emigrating to Nazi Germany. As a result, Hess and his family were forced to return to Germany. Attempts to emigrate to Switzerland or Brazil failed, so they moved briefly back to Düsseldorf before resettling in Unterwössen, a small village in the district of Traunstein in the far south-east of Bavaria, where his daughter attended the Landschulheim Marquartstein, a local gymnasium and boarding school.[2]

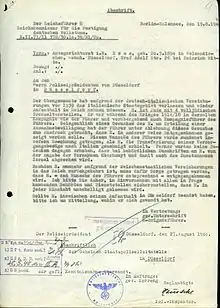

Wiedemann and Lammers had provided assurances that Hess would not be harmed. In August 1940, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, issued a letter to the Düsseldorf Gestapo ordering that Hess should not be "inopportuned in any way whatsoever". Noting that Hess had been "both in the same company as the Führer and briefly the Führer's company commander", Himmler instructed that Hess should be granted "relief and protection as per the Führer's wishes" and asked that he be informed if Hess should leave Düsseldorf. A follow-up letter was sent by Lammers in November 1940, informing Hess that "it is, however, the Führer's wish that you should not be subject to any further restrictions because of your ancestry beyond those required by law." Lammers expressly informed Hess that he was to use the letter for his protection: "I give you this letter, if necessary, to make use [for your protection]".[1]

It is unclear what role Hitler himself played in granting protection to Hess. A case is known of a Jew who enjoyed Hitler's personal protection—his former family doctor, Eduard Bloch, whom Hitler called an Edeljude ("noble Jew").[2] Hitler is known to have felt very close to the other veterans of his regiment. Thomas Weber, the author of Hitler's First War: Adolf Hitler, the Men of the List Regiment, and the First World War, has said that it is conceivable that Hitler knew Hess personally because the two men had been wounded in the Battle of the Somme only a day apart, and may have been initially treated in the same place before being transported together to the same hospital in Germany.[1] However, Weber cautions that the letters of protection may have been organised without Hitler's knowledge by Wiedemann, "because he did the same in other cases involving Jewish soldiers." The letter from Himmler was not found until 2012, when it was discovered in surviving Gestapo files on Jewish lawyers and judges in Germany. It was publicised in the July 2012 issue of the quarterly publication Jewish Voice From Germany and was corroborated by Hess's daughter Ursula.[4]

Loss of protection and enslavement

The protection that Hess enjoyed turned out to be only temporary respite from persecution. Hess's friend Wiedemann was dismissed from his position by Hitler and sent into de facto exile as Consul General to San Francisco. In May 1941, Hess was informed that the protection order had been revoked and that he was now regarded as being "a Jew like any other". Petitions to Berlin were unsuccessful, and in June 1941 he was summoned to the "Aryanization Office" in Munich. Lammers' letter of protection was taken from him and he was sent to Milbertshofen concentration camp near Munich, where he was put to work as a labourer. He was subsequently assigned to the Munich firm of L. Ehrengut and later to a plumber's, Georg Grau, where he served as a forced labourer until 20 April 1945. His wife Margarete remained in Unterwössen, where she lived with her parents, but his teenage daughter Ursula was forced to work in an electrical firm in Munich.[2]

Hess's Jewish mother Elisabeth and sister Berta believed that the protection that he had received also extended to them. As a result, they did not comply with the restrictions imposed on Jews. However, when their case was reviewed in 1942, Adolf Eichmann of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Main Security Office) personally ordered their deportation to the Theresienstadt concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. Berta was subsequently killed at Auschwitz, while Elisabeth managed to escape to Switzerland in February 1945. She later emigrated to Brazil with her son Paul. Hess himself only survived because of his "privileged miscegenated marriage" with Margarete.[2]

Post-war career

After the fall of the Third Reich, Hess was nominated to serve again as a judge in Düsseldorf but declined, as he did not wish to work alongside former colleagues who had been part of the Nazi judicial system. He started a new career in the railways in 1946, and from 1949–55 served as President of the German Federal Railways Authority in Frankfurt am Main. He was awarded a Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany and was given a plaque of honour by the city of Frankfurt in 1970. He died there on 14 September 1983.[2]

Notes

- As all four of Ernst's grandparents were Jewish, it appears that Julius Hess was also of Jewish ancestry and had presumably converted or was brought up as a Christian, though this is not spelled out in the sources.

References

- Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (July 6, 2012). "Wie Hitler seinen jüdischen Kompaniechef schützte". Die Welt (in German). Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Susanne, Mauss (July 4, 2012). "Hitler's Jewish Commander and Victim". Jewish Voice from Germany. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- Rohrbach, Jens Martin (2007). Augenheilkunde im Nationalsozialismus. Schattauer Verlag. p. 25. ISBN 9783794525126.

- "'Hitler's wish' protected Jewish WWI vet". Associated Press. July 6, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2013.